I haven’t seen the Black Panther movie yet; but I’m looking forward to it.

T’Challa, the Black Panther, has for a long time been one of my absolute favorite comic book characters – and I’ve been glad that his mythology has been given the cinema treatment: and that it appears to be doing so well and generating so much conversation.

But, amid all of that conversation (much of which, rightly, is focused on the subject of the first entirely black superhero movie), one thing that probably won’t be discussed is the subject I’m going to cover here now: which gives me a rare opportunity to talk about both my love of comic-book mythologies and my interest in real-world geo-political conspiracies at the same time.

This isn’t an article about the film or even about the character’s history. Rather, it’s about a specific perception I have of the Black Panther mythology and how it relates to particular real-life North-African nation that I’ve written a lot about in the past – specifically Libya, and more specifically the Gaddafi-era Libya.

Now, obviously, I’ll need to justify this – and I will.

Firstly, having not seen the movie yet, I can’t speak for whether the Libya/Gaddafi aspect is prominent or noticeable in the film. But it has definitely been noticeable to me in the source-material – this being the comic books, and particularly in recent years.

That shouldn’t necessarily be surprising – comic-books very often channel or mirror real-world events and are often a very good medium for exploring real-world or contemporary subjects in a different way.

If anyone here has seen the film already, I’d be interested to know whether the connections highlighted in this article below are also reflected in the movie. Similarly, if anyone reads this article and is planning to see the film yet, it might be interesting to note whether the film backs up these observations any further.

Now, for the record, I’m not claiming that the Black Panther mythology was always intended – at its conception in the 1960s – to reflect or parallel real-world Libya or that the character was intended to channel or reflect Gaddafi.

I’m 100 percent certain this was not the case.

At its inception in the 60s, the Black Panther comic book was about other things entirely. In fact, one of my favorite stories about the legendary Jack Kirby is that, when he received complaints about the Black Panther comic and was put under pressure to put more white characters into the book, he responded by having T’Challa – in the very next issue – beating the crap out of the KKK.

Without question, the Black Panther comics originally were – aside from being just superhero fun at the basic level – designed to reflect or speak to entirely domestic social or cultural issues in America at the time.

Rather, I’m saying that the Black Panther mythology has become a Libya analogy over time – and especially very recently.

Now, you could debate where this is deliberate or just coincidental: but one example in particular – which I’ll explain in a moment and which forms the basis of most of this article – is almost certainly deliberate.

Also, someone might argue that – in my observations – the fictional ‘Wakanda’ could be analagous to a number of past or present African (or Arab) societies. Which, in various ways, is true – but there are specific reasons I’m citing Libya, as you’ll see.

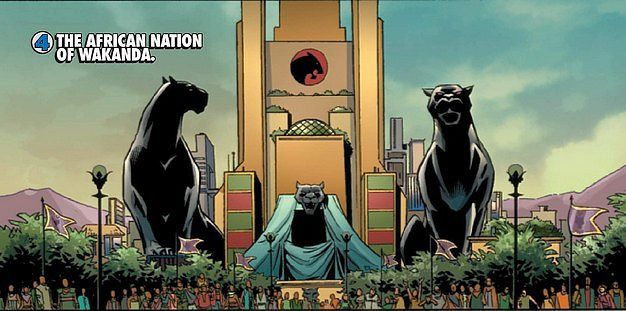

For anyone who doesn’t know about the Black Panther, the character is the king of a fictional African nation called ‘Wakanda’ that exists in the Marvel Universe. Wakanda is presented always as a resource-rich nation, highly developed, and constantly having to deal with foreign interest or violations due to Wakanda posessing a precious natural resource called ‘Vibranium’.

Wakanda is the most highly developed nation in Africa – just as Libya was. Wakanda is also a desert country for the most part, just like Libya. And reference is often made to the tribal nature of Wakandan society and its power structure – again, mirroring Libya. T’Challa rules partly thanks to the support and confidence of the different tribes, just as Gaddafi did.

Although ‘Vibranium’ is a fictional substance, it has for a long time seemed to me to be a metaphor for oil. Because all these foreign powers or organisations want vibranium, they are constantly trying to involve themselves in Wakanda – and, across many stories over many years, the very protective, nationalistic Wakandans are constantly alert to defend their country, sovereignty and resources.

That’s arguably the core of the Gaddafi/Libya parallels (Libyan oil reserves made it a target for decades) – but it goes a lot further.

In fact, while the idea of Wakanda and T’Challa as fictional representations of the former Libyan Arab Republic and Gaddafi have been occuring to me for a few years, it wasn’t until about a year-and-a-half ago that this connection became firmly solidified in my perception.

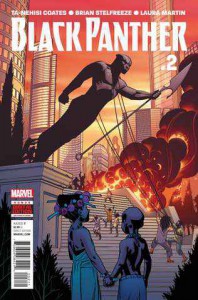

The final reason was a Black Panther comic-book series that was so obviously a retelling of the fall of Gaddafi and the collapse of Libya that it seemed intentional. The series was written by a well-regarded journalist, educator and expert in social and political issues – a MacArthur Genius and National Book Award-winner named Ta- Nehisi Coates.

The initial arc of the story was titled ‘A Nation Under Our Feet’.

And, as I will shortly elaborate on, the more I read it a year ago the more I found that ‘A Nation Under Our Feet’ closely paralleled (surely on purpose) the very real crisis that unfolded in Libya in 2011.

As someone who researched and wrote on the subject of the Libyan ‘revolution’ at length (and in fact compiled a book on the subject), the analogies struck me throughout this story – and is a primary reason I found it such a compelling book.

The story in this series is roughly as follows: the fictional African nation of Wakanda is in turmoil, with the people rising up against T’Challa’s rule. There are mass riots and protests, quickly turning to violence. The early chapters are told from T’Challa’s own perspective, as he tries to cope with the suddenness and the scale of the uprising and tries to figure out how on earth he is supposed to deal with this. Having for years been on-guard against foreign, outside threats, he is taken completely off-guard by this threat rising from within his own population.

At some point, as the story progresses, T’Challa and his forces are forced to even attack their own people. But we see him struggling with this problem of whether he can bring himself to attack his own citizens in order to stop them bringing the country to ruin.

As the saga progresses over several months, we learn that the people are being goaded into revolution by sinister agents and agencies; some of them being home-grown traitors to the nation, some being foreign powers. Evidently, there is a foreign-backed conspiracy behind the unrest.

Anyone familiar with the events of the Libya collapse in 2011 could not read ‘A Nation Under Our Feet’ and not see it as a retelling or chanelling of those events. A restless population rising up against their powerful figurehead, manipulated by cynical outside agencies into doing so, the figurehead/ruler (T’Challa/Gaddafi) struggling with how to deal with this threat to the nation, etc.

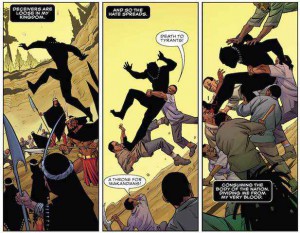

Reading ‘A Nation Under Our Feet, Part 1’ in particular, the points of comparision come up so frequently throughout. But take page 6 of Black Panther #1: T’Challa has lines like, ‘The hate did not spread on its own. Deceivers are loose in my kingdom’. You could find Gaddafi saying more or less the exact same thing back in 2011.

On the very same page, you then see a mob of angry Wakandans seizing T’Challa, one of them crying out “Death to Tyrants!” This scene immediately echoes Gaddafi’s death in October 2011, when he was seized by the viscious mob and executed.

A couple of pages later, one of T’Challa’s attendants urges him to withdraw from the angry mob, warning “call the soldiers back – we cannot massacre our own people.” This, again, directly echoes Gaddafi issuing orders to his army generals (in the initial stages of the unrest) to not open fire on the crowds, no matter how violent they became.

It would not surprise me in the least bit if Ta-Nehisi Coates – an expert in social, political and African affairs – has deliberately used the Libyan nightmare as a basis or inspiration for this storyline.

I haven’t seen Coates say this anywhere, but the similarities between the real-life Libyan horror story and this fictional Wakandan story are so strong that I would be astonished if there was no conscious mirroring going on here.

In Coates’s storyline, there are even visual cues in the artwork: not just the abundance of the color green (the Libyan, Gaddafi-era colors), but, for example, in a simple image of T’Challa moving across the water (Black Panther #1, page 24). In this image, the way the skyscrapers and apartment blocks line the coast is immediately reminiscent of Gaddafi-era Tripoli.

There is no escpating that Birin Zana – the ‘Golden City’ of Wakanda – does look a hell of a lot like Gaddafi-era Tripoli.

For the record – and to support my argument – I can also cite as far back as Black Panther Vol.4 #21 (during the original Civil War storyline in 2006): in that book, the X-Men’s Storm points out that Wakanda secretly funded Nelson Mandela’s anti-Aparteid movement for years.

It is a known fact that the biggest sponsor of Mandela and the ANC in the real world was Gaddafi and Libya.

If A Nation Under Our Feet #1 was striking for its real-world parallels, the cover for Black Panther: A Nation Under Our Feet #2 really, fully confirms the point. The image shows a large statue of the Black Panther being brought down by angry citizens in the street.

It’s an image that very clearly echoes real-world events, uprisings and coups in recent years. The backdrop also makes it look a lot like Tripoli again (Libya) – though, in fact, the general idea is more referencing the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Baghdad and the famous footage of people pulling down Saddam’s statue.

What is also interesting about this series is that T’Challa – our ‘hero’ and a Marvel standard – is at times depicted with the trappings almost of an African or Arab dictator.

There isn’t any real attempt here to water him down or make him more compatible with Western-centric sensibilities. He is very much a figure who believes entirely in his divine, sacred right to rule and in the power of his position. He is even shown having ‘Secret Police’ that work for him (the ‘Hatut Zeraze’). While at no point is he depicted as being brutal or an oppressor, it is nevertheless interesting and even somewhat refreshing that Coates doesn’t try to gloss things over or avoid the reality that Wakanda isn’t meant to be an entirely open, liberal democracy.

It is a dictatorship.

In the Marvel world, what has always been particularly curious is that T’Challa is never presented as anything other than a hero – but he is, nevertheless, a dictator in his country: and this fact is never glossed over. The perception is always that the fictional Wakanda is a very delicate society that works in a very specific way that outsiders don’t always understand – again, evoking real-world Libya in the Gaddafi era.

What this Black Panther series further reinforces is the reality that some countries and societies – in Africa and elsewhere – are built on very unique, delicate and specific dynamics, cultural idyosyncracies and sensibilities, that evolve and coalesce over many centuries: and that high-minded foreign powers should always think twice before storming in and knocking over the entire edifice in a misguided attempt to ‘bring Western democracy’, as if it can work that simply.

The Libya analogy is cemented further in Black Panther: A Nation Under Our Feet #4, when we learn for certain that the unrest in the country is being manipulated by foreign hands: echoing how the CIA, French Intelligence and other external actors were revealed to be guiding the Libyan unrest in 2011.

In #5, the story gets dirtier and more grey as T’Challa seeks out the counsel of some highly dubious figures, counter-terrorism and counter-revolutionary experts, conveying the depth of his dilemma and what he is being dragged down to in order to try to save Wakanda.

In actual fact, it is a trick to fully and finally discredit him among his people – and, by this point, the real-world/Libyan similarities are so thick and fast that I don’t even bother to note all of them any further (we also have the rebels being specifically referred to as ‘terrorists’ and we even have a suicide-bombing occuring).

Again, I’ll be interested to see whether the film incarnation of the Black Panther reflects any of this or not.

It’s unlikely that the widespread hype and discussion over the Black Panther and what it represents will include any of what I’ve discussed here – or any reference to Libya or Gaddafi. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

Not that any of this has much to do with why the Black Panther is such a great character or why the mythology is so rich: but with subjects like this, it is nevertheless always interesting to observe what gets discussed (or deliberately noticed) and what gets ignored (or deliberately ommitted from discussion).

Ta-Nehisi Coates, who is a journalist and National Correspondent for The Atlantic, was an inspired choice of writer for this series and did a great job creating a rich, absorbing scenario, mythology and re-framing of an iconic character.

In my opinion, he also clearly used the platform as a way to retell the fall of Libya in a different way. As far as I know, he has never said this openly – and he has probably never even been asked about it. But it’s all there, for anyone with the eyes to see it.

For any comic-book readers who haven’t read this book – or any new fans of the Black Panther (after seeing the movie) – I highly recommend getting a copy of the A Nation Under Our Feet collection.

And for anyone who happens to be both a comic-book or Black Panther fan and someone interested in or versed in the Libya Conspiracy – which, I admit, is likely to be a very small number of people – this series will probably be a fascinating read.

See all ‘LIBYA’ Articles here.

See all Comic Book articles here.

Interesting analysis of the parallels between the real world Libya and the comic book saga.. Mythology can be interpreted on different levels.

One thing is for certain: post Ghaddafi Libya is much worse now. This is yet another example of Western nations making things worse by their meddling and intervention.

Thanks, larryzb. Libya should’ve been the *final*, conclusive example to us of why Western military force to topple regimes we don’t like is not the answer.

They’ve gone – in the space of a few years – from massive development, infrastructure and economy (as well as free universal health care, etc), to *literally* SLAVE MARKETS. Actual, real slave markets.