It is 20 years since the first broadcast of the finest SF TV serial to have ever graced the small screen. J. Michael Stracynski’s Babylon 5 set a standard for science fiction storytelling in television that hasn’t been matched since.

It is a show cherished by a devoted fan community that probably exceeds any comparable show in terms of the degree of that devotion and the sense of precious ownership of its rich and complex world and mythology.

And unlike its closest SF ‘rival’, the Star Trek franchise, Babylon 5 didn’t need a couple of seasons to find its quality-level as ST shows tended to need, but was terrific from the very outset, its architect and chief writer possessing a clear, lucid vision and plan for the show, the story arcs and the characters. It’s a perfect example of how an individual mind with a clear vision and the freedom to pursue that vision can result in something more cogent than a show being run by a committee of people all wanting their input, which is what most shows tend to be.

Which, by the way, is not a dig at Star Trek shows – I love Trek; and would still hold both the original Star Trek series and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine above Babylon 5 in my own preference ranking. And yes, these things are very subjective.

But what Strazynski did with Babylon 5 was unique and very special in the history of television – he created a fully-realised ‘saga’ with a beginning and an end and a carefully thought-out story comprising the five seasons inbetween.

This clarity of vision and intent meant that, for one thing, Babylon 5 rarely ‘wasted’ time or went off on tangents, but was from the very beginning headed in a definite direction. This obvious degree of focus and intent imparted the series with a sense of urgency from relatively early on; a sense of urgency and momentum that didn’t really abate until the end of the fourth season. Which is a remarkable accomplishment in storytelling and screen-writing terms.

Ironically it wasn’t until the show’s fifth and final season that this sense of urgency and momentum evaporated somewhat, which is strange as usually it’s in a final season that a series really picks up momentum. Even though I’d have been happy with another three or four seasons of Babylon 5, I’ve always felt it might’ve worked better as four seasons and not five.

In truth the fifth season had some stories, elements and episodes that didn’t do much to enhance the show’s overall legacy, acting as something of an extended anti-climax (notwithstanding the final episode itself; though in fact ‘Sleeping In Light’ had been filmed as the Season Four finale anyway and held back when a fifth season had been given the green light).

It was a final season that suffered from the loss of some key cast members and the fact that the series main story arcs had already been wrapped up in Season Four; it was of course studio execs that caused this problem, as Strazynski wasn’t told until very late whether a fifth season would be green-lit or not. It is always therefore been a great ‘what if’ in my mind to wonder what the final/fifth season would’ve been like if Strazynski had known it was guaranteed; might many of the key story elements from Season Four have been extended into Season Five and given more breathing space?

Would Claudia Christian have stayed on and would Jason Carter’s Marcus Cole still have been killed off or would he have stuck around to enliven the final season?

But that’s a relatively minor gripe given the overall quality level of the series as a whole; years removed now from the time of broadcast, we can let go of gripes and minutiae and appreciate just how superb and special a series J. Michael Strazynski has left us with, with its massive mythology, its fully-realised characters and its epic story.

And what a story; from the Earth-Minbari War to the Shadow War, from the redemption of G’Kar to the tragedy of Londo Mollari, and with so much else besides, Babylon 5 is the standard-setter for the television epic, attaining a degree of continuity and pathos that almost always eludes the medium of television and can usually only be found in comic-books or novel series.

The quality and style of this storytelling often reminds me of another permanent favourite of mine, the brilliant 1970’s BBC drama I, Claudius.

Babylon 5 could in some ways be described as ‘I, Claudius In Space’. Certainly the character arc of Londo Mollari – one of the great characters and character journeys in any fiction, in my opinion – plays like something right out of I, Claudius.

But this is perhaps not too surprising, given the obvious parallels between the Centauri Republic and Ancient Rome and between Peter Jurasik’s character and probably the Emperor Tiberius (that are clear parallels between George Baker’s superb portrayal of Tiberius and Jurasik’s Mollari).

The key to any great series, no matter how great the story vision, is a good set of characters that need to be either engaging or likeable. Babylon 5 had the right mix of both. The ‘main’ cast possessed that basic likeability from the start and with a good inter-dynamic chemistry; the likeable everyman of Garibaldi, the dry wit of Ivanova, the down-to-earth nobility of Stephen Franklin, the Arthurian-style English charm of Marcus Cole, all permanently enjoyable and sympathetic characters to watch.

However, arguably the two most memorable, most standout characters of the B5 universe are Londo Mollari and his great foil G’Kar.

Both of them – Londo (superbly portrayed by Peter Jurasik) and G’kar (equally superbly portrayed by the late Andreas Katsulas) – are not only fascinating, classic characters in their own right, but their relationship with one another throughout the five seasons of the show remains to my mind the most memorable, most endearing, and best written element of the entire series.

Both larger-than-life, charismatic figures and both tortured, complex characters, their character arcs play out across the series like epic poems, Greek tragedy and moving morality plays. They are two extraordinary characters and that’s something that elevates Babylon 5; anyone writing or producing a TV series would, you suspect, kill for the privilege of having two actors embody and portray such beautifully written characters over five years with such care, nuance and artfulness.

It brings me again to the I, Claudius analogy and the performances of, say, Derek Jacobi (Claudius) or John Hurt (Caligula); to my mind Jurasik’s Mollari and Katsulas’s G’Kar are on that level. The two of them are, in my view, the heart, the core, of what makes Babylon 5 so special.

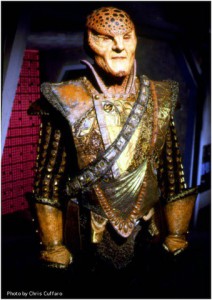

The mythological power of the series and its fictional arena is also one of the defining qualities, particularly its rich galactic tapestry of alien civilisations and races, all fully furnished with their distinct cultures and idiosyncrasies. The violent, aggressive and oppressed Narn (who always served as a Palestinian metaphor to my mind), the sophisticated imperial Centauri, the religiosity of the Minbari, and then there were the enigmatic Vorlons and the demonic Shadows.

The cultures and societies that made up B5‘s political tapestry were much more fully realised and richer in depth than most of the equivalent races/powers in the Star Trek franchise, the latter often ending up being almost cliches of themselves and objects of single-episode plot convenience.

I also can’t think of any TV show that set up mysteries and intrigues so far in advance and answered them at such a varied, though ultimately satisfying, pace, so that it didn’t feel like contrived staging or ratings ploys but simply organic developments in a fictional world that was so complex and multi-faceted that the show could answer numerous longstanding questions whenever it wanted and still have enough mystery and intrigue left to keep viewers watching and wondering.

A few notable other shows have tried to do this but have failed to do it anything like as effectively as Babylon 5.

Babylon 5 broadly didn’t resort to SF or televisual cliches either; for example its only significant ‘time-travel’ story – War Without End – avoided nearly all the cliches of time-travel stories in other franchises, never feeling like anything other than a massively relevant part of the wider storyline of the series. Most importantly it didn’t have a reset switch; B5 tended not to have the reset switch in general, which was another of its highly refreshing properties.

Babylon 5 wasn’t perfect; there were always some things I felt could’ve been better, but these were primarily issues of budget and funding – specifically, for example, the costume-design could’ve been a lot better than it was and some of the set design too.

And in truth some of the special effects sequences look very dated and unconvincing now (and actually some of it looked below-par even at the time), with the show having always gone for a more (at the time) futuristic, CGI style for those types of sequences, as opposed to the more standard, but also more realist, model-based style of effects sequences in, say, Deep Space Nine or the other Star Trek shows.

I also always felt there were some weaknesses in casting, but more so the guest actors and minor castings as opposed to the main or recurring ensemble. A major example of this would be the telepath arc in the final season; the story itself should’ve been good as written, but it was ruined by atrocious casting choices, especially the main character of Byron, which rendered most of those scenes unwatchable. It wasn’t the only instance of below-par casting for guest characters undermining the quality of certain episodes. These elements detracted at times from the overall quality of some of the episodes.

The fact was, however, that the storytelling, along with some of the key characters, was so good that these weaknesses – weaknesses that might’ve sunk another show – were more than compensated for on the balance.

B5 isn’t a series I rewatch regularly anymore; not because I don’t love it, of course, but because it’s not a series to watch casually, rather it demands the respect of a time commitment to fully take it in in all its depth and layers, like I, Claudius or HBO’s Rome (both shows that I also adore, but don’t go back to as often as I would like).

The second reason is because the sad deaths of several key cast members in the years since the series ended has added an additional emotional layer to the experience; I struggle, for example, to watch Stephen Franklin scenes without thinking about Richard Biggs’s tragically young death in 2006, or to watch Michael O’Hare in the first season without thinking about the subsequent revelations about his mental health.

But the other reason is of course the fact that the stories, themes and characters of Babylon 5 are so well embedded in my consciousness anyway that I can wait several years or so before coming back to dock at the station again; and then of course appreciate it all the more all over again.

Even now, however, there is sometimes a divide between SF fans who utterly adore Babylon 5 and those who just ‘don’t get it’ (hence the recurring gag in The Big Bang Theory of Sheldon not getting Babylon 5 and criticizing its “bad dialogue”).

I could’ve easily been one of those who ‘don’t get it’, having been initially put off by the aforementioned weaknesses in set and costume design and initially finding the show difficult to get into aesthetically. As a result of that I didn’t start watching the show properly until the third season was being broadcast and then I had to go back and watch the first two seasons. I’ve always been glad I gave it the time – because Babylon 5 is one of the greatest fictional worlds I’ve had the pleasure to absorb (and keep) in my mind-scape.

And I, like many others, remain grateful to J. Michael Strazynski for sharing his vision and to those key, principal actors and other creative forces that helped bring it to life.

On that point about the “bad dialogue”; there is some pretty poor dialogue scattered about the series, particularly in regard to overblown speeches and instances of sentiment being laid on too thick. But then there are plenty of instances of superb dialogue too; it really does just depend on what episode you’re watching.

Fans of the show meanwhile might differ and bicker over smaller details for decades to come – for example, I always preferred Sinclair to Sheridan, and always preferred Andrea Thompson’s Talia Winters to Patricia Tallman’s later Lyta Alexander character, etc – but they will always be united in the broader matters and overall celebration of the series as a whole, what it set out to do and what it accomplished.

I always wonder with a concept like Babylon 5 how easily it could’ve just not been picked up by a studio like Warner Bros. We can only imagine how many genuinely worthy concepts and outlines for shows have never been given the green light or the funding; how many great ideas have been consigned to the waste-paper basket due to studios and executives not ‘getting it’ or, worse, being unwilling to give something too ambitious, too unusual or too not ‘in vogue’ a chance to be developed, especially when it comes to SF.

There have probably been more great ideas, more still-born classics-that-never-were, than there have been great series actually made.

Luckily for us, J. Michael Strazynski’s Babylon 5 was one of those that managed to get through.

My understanding was that the arc was actually meant to be seven seasons… there was a metric TON of mostly unresolved back story too. But when B5 hit its straps, it was nearly beyond compare. There has never been a TV show before or since where my friends rang immediately after an episode and were yelling down the phone line “Did you see that!??! Did you SEE that?!?!?!?”.

Amazing stuff 🙂

I doesn’t surprise me that there was lots of unused, unresolved story, as you say Helena. Regrettably – unlike with DS9 – I never had the shared experience of talking to friends about B5 episodes, as none of them watched it! Thanks for commenting; I still miss the show.