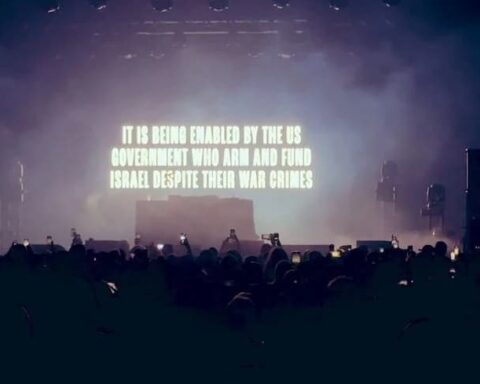

“I’ve always detested mechanized dance music, its stupid simplicity, the clubs where it was played, the people who went to those clubs…” said the email-turned-billboard.

“Basically all of it: 100 percent hated every scrap.”

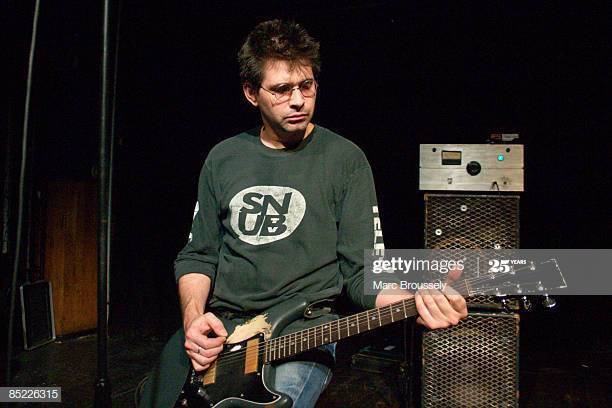

Oscar Powell is the boss of a music label called Diagonal, and also puts out music as ‘Powell’ via a label called XL. His latest single, ‘Insomniac’, features a vocal sample from indie music legend and producer (or ‘recorder’, as he might prefer to be called) Steve Albini, concerning Powell’s request to sample his vocals on the track.

Now prior to the single’s release, Powell had contacted Albini in order to get permission to use the sample (dating back to Albini’s classic ‘Big Black‘ days), explaining at the same time how much Big Black’s music had meant to him.

Then, in true Steve Albini style, Albini not only offered his permission; he also wrote a comprehensive diatribe on why he utterly detests synthetic dance music and everything that goes along with it. When an amused Powell then asked if he could use Albini’s e-mail rant to actually promote the single, the ever blunt Albini replied “Still don’t care.”

Not missing the chance to stir up extra interest in the single, XL purchased a billboard in London (Commercial Street) to promote the release by displaying the text of Albini’s email.

Albini, predictably, has been somewhat the object of brief mockery on account of his opinions, no doubt drawing disapproval from some of the electronic/dance music community.

Others no doubt will agree with his sentiments, while others will neither agree nor disagree but rather enjoy Albini’s text all the same. He was of course just being honest, as he always is. “I am absolutely the wrong audience for this kind of music,” he wrote. “I’ve always detested mechanized dance music, its stupid simplicity, the clubs where it was played, the people who went to those clubs, the drugs they took, the shit they liked to talk about, the clothes they wore, the battles they fought amongst each other,” he said, not mincing words. “Basically all of it: 100 percent hated every scrap.

He continued, “The electronic music I liked was radical and different… when that scene and those people got co-opted by dance/club music I felt like we’d lost a war. I detest club culture as deeply as I detest anything on earth. So I am against what you’re into, and an enemy of where you come from but I have no problem with what you’re doing.” He then concludes in wonderful Albini fashion, “In other words, you’re welcome to do whatever you like with whatever of mine you’ve gotten your hands on. Don’t care. Enjoy yourself. Steve.”

The incident took off in a big way a week or so ago, circulating heavily around the music press.

However, it probably wasn’t meant to become such a big thing. In a subsequent interview, Mr Powell explains that he has nothing but respect for Albini and wasn’t trying to make a joke out of him at all. “I got an email from Steve, and first and foremost thought ‘this is just incredible writing’. It made me laugh and he was saying things that I believe about music, so it was a chance to say something about the state of electronic music and see what people thought about it. There is a lot of shit electronic music around. It’s become this coffee table, festival-going alternative to rock music. I liked the fact that he was attacking that…”

One suspects anyhow that Albini wouldn’t care if he was being made fun of; and, if anything, would probably welcome it, being someone who would even revel in a degree of trolling or criticism. After all, he’s had a long history of speaking his mind and bypassing niceties, while inevitably being criticised by some for it and lionised by others.

It’s hard not to lionise Steve Albini, though he almost certainly would hate it and wouldn’t be remotely flattered. The man is a punk-rock and indie music legend and pioneer who has been in some of the most bad-ass bands around – Big Black, Rapeman, Shellac – and beyond that has produced or ‘recorded’ some of the greatest albums ever made.

Along with an extraordinary list of underground acts, underground-underground acts (The Bats Pajamas or the brilliantly named ‘Joan of Arse’, for example), obscure records, no so obscure ones (Chicago!), things you’ve never heard of and will probably never listen to, and things you most certainly have heard of and do listen to, Albini has over the years provided his services to Nirvana, PJ Harvey, Pixies and the Breeders, the Jesus Lizard, Bush (say what you want about Bush, but Razorblade Suitcase is their best sounding album for a reason), Fugazi and even Veruca Salt (‘Blow It Out Your Ass It’s Veruca Salt!’), among many others.

Also considering how wealthy he has chosen not to become, it is hard to think of anyone cooler than Albini or as much an embodiment of a real punk-rock ethos, nor of anyone so permanently and so entirely anti-mainstream music industry. Also, just for good measure on the cool-as-shit front, he played *all* of the instruments (except saxophone) on Big Black’s debut EP, Lungs.

The reason I say his email made my week isn’t just because I broadly agree with its content; but because one often craves consistency (even cultural consistencies) in one’s landscape, and there’s a nice kick in seeing Albini still winding people up all these years later, still being as blunt as ever and still generating attention on account of it.

The billboard seems just as much a homage to Albini as anything else.

Albini’s blunt opinions on the music industry, as well as on the shifting trends in music of various eras (and his generally dim view of most of those trends), have received considerable exposure plenty of times over the years, giving him a reputation, fairly or not, as the most intransigent of musical pioneers (pioneer or purist, or both – it’s hard to decide; and he probably doesn’t care, so we probably shouldn’t either).

Anyone who bluntly states ‘the music industry is a parasite’ is someone who knows how to cut through nonsense and make the point, just as he’s done in this highly publicised letter on dance/club music. Given a music industry that is now unashamedly a pure entertainment/profit industry entirely built on artifice, Albini’s scathing attitudes towards the mainstream music ‘scene’ of two decades ago are more relevant now than they were twenty years ago (though he is much more sympathetic towards modern file-sharing, copyright free music and the much more accessible artist/fan relationship in the Internet age).

The fact is that, as cynical as the industry might also have been twenty years ago and as much as he might’ve loathed it then, there were nevertheless major labels funding and putting out music as extraordinary and as otherwise non-‘mainstream’ as Nirvana‘s In Utero and PJ Harvey‘s Rid of Me (both absolutely landmark albums and both being works with which Albini is permanently associated); there’s no music of equivalent quality or significance that major corporations are interested in putting out (or ‘taking a chance on’) today.

Some of Albini’s earliest rants were for indie zines like ‘Forced Exposure‘. Much later he also wrote a much-referenced article on the conduct of major record labels for the journal ‘The Baffler’ in 1994. Albini’s essay, ‘The Problem With Music’, laid out his adversarial view towards major labels, which he regarded as being run by “faceless industry lackeys” and holding bands and artists to ransom with bad contracts and unjust royalty splits.

He hasn’t changed much; and so much the better.

That Albini remains an extremely significant voice in music is beyond question; and countless music or culture enthusiasts actively seek out his opinion. In November last year, Albini was invited to deliver the keynote speech at the ‘Face the Music’ conference in Melbourne; in it, he discussed the evolution of the music industry since he himself had begun his musical working life in the early eighties. Among other things, he defined the (pre-Internet) corporate music industry as a system “aimed to perpetuate its structures and business arrangements, while preventing bands (except for ‘monumental stars’) from earning a living,” while contrasting it with the realities of the independent music scenes, which encouraged resourcefulness and allowed musicians to make a reasonable income. See the full video here.

Kreative Control also had a really good, insightful interview with Albini recently; you can listen to or download the podcast here.

____________________

The recent XL billboard incident won’t qualify as his most famous letter either. Another somewhat famous letter of Albini’s was one he wrote to Kurt Cobain, Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl prior to taking on the then extremely high-profile job of producing Nirvana’s final album, In Utero, in 1993.

Explaining his methods, standards, and conditions for the project at great length, he wrote “I’m only interested in working on records that legitimately reflect the band’s own perception of their music and existence. If you will commit yourselves to that as a tenet of the recording methodology, then I will bust my ass for you. I’ll work circles around you. I’ll rap your head with a ratchet. I have worked on hundreds of records (some great, some good, some horrible, a lot in the courtyard), and I have seen a direct correlation between the quality of the end result and the mood of the band throughout the process. If the record takes a long time, and everyone gets bummed and scrutinizes every step, then the recordings bear little resemblance to the live band, and the end result is seldom flattering. Making punk records is definitely a case where more “work” does not imply a better end result. Clearly you have learned this yourselves and appreciate the logic.”

In fact Albini’s involvement in In Utero is said to have come about partly on account of the work he’d just done on PJ Harvey’s omni-classic Rid of Me album (in addition to Nirvana’s love of Albini’s renowned work with the Jesus Lizard and on the Pixies‘ Surfa Rosa). According to Polly Jean Harvey herself, the bulk of the recording for Rid of Me was done in just three days; which is extraordinary for an album now considered so monumental. But she had sought Albini specifically for the recording; “I knew I wanted to work with Steve Albini from listening to Pixies records, and hearing the sounds he was getting, which were unlike any other sounds that I’d heard on vinyl,” she has since explained. “I really wanted that very bare, very real sound. I knew that it would suit the songs. It’s like touching real objects or feeling the grain of wood. That’s what his sound is like to me. It’s very tangible. You can almost feel the room.”

When Cobain and Nirvana expressed interest in using his services for their highly-anticipated follow-up to Nevermind, Albini sent Nirvana a copy of the recently completed PJ Harvey record as an example of what the studio could sound like if his very particular recording techniques and studio philosophies were adopted. “We had a short recording schedule because I have found that records don’t get better if you work on them longer. They get better if you work on them with more attention, but not necessarily over a longer period. Having extra time at your disposal is kind of an inducement to worrying the record and making it weaker,” he had explained.

Responding to music-journo criticism of Rid of Me and specifically of Albini’s techniques (among other things, a criticism was made that Polly’s vocals are too weak in places, drowned out by the noise), Albini has a typically uncompromising response; “Minor music-business functionaries having an opinion about how a singer should sing or how her band should sound — all those people can go fuck themselves.”

The music press of the time of course made a sensation out of the fact that Nirvana – then an enormous act and cultural phenomenon – was going to work with so anti-industry, anti-mainstream a producer as the notorious Steve Albini of Big Black and Rapeman fame (or infamy, depending on who was writing any given article). It would be fair to say that the record label and management were terrified of what the album was going to turn out like, but it would be fairer to say that the music press exaggerated things to a large extent for sensationalism; all of which, however, aided the fascination over In Utero prior to its release.

Eternal controversies over the fact that the original Steve Albini mixes of the album were not what ended up being released (REM producer Scott Litt was instead brought in to remix key tracks) only added an additional layer of intrigue to the mythology surrounding so legendary a release.

Fans still talk about the Albini In Utero mix – the In Utero that never was – like it’s a lost Da Vinci painting or Orson Welles movie; though Albini himself dismisses this mythology and insists that the existing version of In Utero is the ‘real’ version, if for no other reason than that it’s the version the band chose and was happy with.

“That record would’ve changed the course of popular music…” is what influential UK music journalist Everett True said of the advance tape of the original Albini In Utero mixes that he’d been leaked by Courtney Love prior to the remixing.

In the end, regardless, In Utero was an artistic masterpiece and one of the most astonishing albums ever released, and Albini’s methodologies are patently evident on most of the tracks, which, in terms of the sound dynamics (and especially with the drums), brought Nirvana’s sound to a whole new level. What PJ Harvey says of Rid of Me – “you can feel the room” – applies just as much to In Utero; just listen to the drums on ‘Scentless Apprentice’, for example.

In terms of having his work partly vetoed in favour of additional producers, Albini had been through this before, particularly with Fugazi’s In on the Kill Taker album (1992). The sense in both cases is that he doesn’t really mind and he entirely respects the artists’ final decisions; in the case of In Utero, most of his displeasure at the time no doubt came not from his relationship with the band but from having to deal at all with a high-profile project on a major record label/corporation and with all the accompanying press attention and hype, all of which he despised and resented having to be caught up in (much like Kurt Cobain himself).

But then Albini is Albini; he doesn’t like to play games, mince words or deviate from his ways or philosophies. When I recently watched Dave Grohl’s much-talked-about Sonic Highways series of docu-films, it was no surprise that the most interesting segment of the entire 8-hour marathon was the part with Steve Albini (and not the big finale of the Grohl interview with President Obama).

To this day, he doesn’t receive royalties for anything he records or mixes at his own recording facility, unlike most other engineers and producers, especially those with his level of both experience and renown. Pretty much any other producer with his CV would be raking in extraordinary sums of money; from just Nirvana and PJ Harvey alone, Albini could’ve been a very rich man, but, on principle, chose not to be. Instead he has almost been bankrupt on more than one occasion, even if he is generally able to make a reasonable living when work is steady.

But as he wrote in his letter to Nirvana prior to the In Utero sessions, “I would like to be paid like a plumber: I do the job and you pay me what it’s worth. The record company will expect me to ask for a point or a point and a half. If we assume three million sales, that works out to 400,000 dollars or so. There’s no fucking way I would ever take that much money. I wouldn’t be able to sleep.”

Getting back to the billboard/letter, it’s also difficult not to agree with him on most of the club culture and dance music scene. Which risks sounding snooty or like a music-genre elitist; but judging by Powell’s interview, he also seems to agree himself that there’s a validity to what Albini was saying.

There usually is.

I hate dance music as well and going to dances. They are popular out here to meet people but you can’t talk it is so loud I don’t know how anyone really does that.

All hail Albini the Great. (reading this made me want to go dig out my old Shellac CD. Haven’t listen to that in a while…)

Ah, I’ve lost a lot of my old CDs; I don’t think I have any Shellac anymore.