A magical star leading three mysterious ‘wise men’ from the East across miles and miles of wilderness to a small, obscure town.

And a troubled husband and wife travelling on donkey, social outcasts turned away by one apathetic towns-person after another, desperate for a simple act of human compassion to offer a place for the woman to give birth to an unplanned child who may or may not be magical in nature.

There has always been something so compelling about the Nativity narrative, which has become so permanently established in a universal, collective consciousness that it seems to have long since transcended religion. It’s the stuff of enduring myth and certainly one of the greatest stories ever told.

Whether or not any of it actually happened is very debatable; and even if it did happen, it is highly unlikely to have happened in the way the tradition holds or the gospels record. But the gospels were always more a mixture of carefully measured 1st century propaganda and broader mythologizing for the sake of propagating a new religious sect than they were about being a strictly historical account. Certainly the Biblical texts – Old and New Testament alike – cannot be regarded as reliable history for the most part, but more as a sort of manifesto for an emergent religious and spiritual system; or, at best, a highly romanticised, tailored interpretation of what may at the basic level have been real, historic events to some degree or another.

Most objective academics agree that much of the gospel narratives, which are conflicting and inconsistent in various places, were carefully composed for various contemporary purposes and not to be a strictly literal ‘truth’; at least not in the same way we would regard modern ‘non-fiction’ publishing.

As with much ancient writing, the line between fact and fiction was very blurred and was often not even considered important; the overriding narrative or the ‘message’ being seen as more paramount than the integrity or reality of the information. This is also exacerbated by the fact there were a great many other ‘gospels’ and writings around, not just the four Canonical Gospels that were selected for the New Testament.

It is clear that the Gospel writers had a conscious theological need to place Jesus’s birthplace in that specific location in order to fulfil earlier Jewish prophecy concerning the Jewish ‘Messiah’ coming from the line (and city) of David, specifically Bethlehem.

But Jesus was thereafter never once referred to in any text as ‘Jesus of Bethlehem’ but as Jesus ‘of Nazareth‘. The birth was placed in Bethlehem to suggest the Messianic descent (from David) to first century Hebrews in order to convince them Jesus was the ‘Messiah’. This is even directly admitted in various passages, for example in the text of Matthew’s Gospel; “So all this was done that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet.”

The conflicting genealogies in the gospels of Matthew and Luke are also an obvious, if convoluted and problematic, attempt to demonstrate a descent of Joseph from King David (and ultimately the Biblical ‘Adam’, who himself was a bastardized version of a character from older Sumerian creation mythology), therefore contriving a kingly ‘pedigree’ for Jesus.

It’s also highly unlikely a heavily pregnant (eight to nine months) Mary would’ve travelled on a donkey all the way from Nazareth to Bethlehem; and it is further called into question whether she would’ve even needed to, as it is considered unlikely that Augustus would’ve called for a census in Judea at all, with Judea not strictly speaking being under Roman control at that time.

The forced Roman census “of all the known world” depicted in the gospels and the Nativity tradition is generally highly refuted. There is no record of Augustus’ decree that “all the world should be enrolled”. As many have pointed out over the years, it would’ve been extremely chaotic and unmanageable for literally every Jew anywhere in the world to have to return home to their ancestral origin or birthplace in order to be registered and it wouldn’t have been in keeping with the highly organised and efficient Roman systems. Roman documents demonstrate that taxation was generally conducted at the provincial level and administered by the provincial governors.

Augustus in particular was a highly efficient and intelligent ruler and it is unlikely he would’ve invited such chaos by issuing a nonsensical decree when it would’ve made more sense to tax or assess people in their places of work and residence rather than forcing people to make long journeys back to wherever their distant ancestors happened to have come from (according to the genealogy given in Luke, David had lived *forty-two generations* before Joseph – and this was apparently the sole reason for Joseph taking his nine-months pregnant wife on a long and difficult journey to Bethlehem on a donkey).

But Bethlehem is the prevailing myth that is firmly resident in our consciousness, replete with its evocative imagery and connotations, the subject of countless paintings and art, Christmas cards, school plays and evocative dioramas.

Myth is, in the long-term, probably more powerful than historical fact; so much so that a deeply established myth or image can be wholly and deeply believed in even long after information has been demonstrated to cast serious doubt on its reality.

And I am not suggesting that’s a bad thing either; which I will argue shortly.

The virgin birth itself, which was also influenced by other Middle-Eastern traditions, isn’t affirmed in all the gospels. Moreover, this too was probably necessitated by the editorial desire to fulfil prophecy; in this case, a fulfilment of Isaiah 7:14 – ‘Therefore the Lord Himself will give you a sign: Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel’.

We also know that Jesus wasn’t born when tradition suggests he was, neither in terms of the year nor even in terms of December 25th. The year of birth was several years off due to the miscalculations of Dionysius Exiguus, the 6th-century monk whose calculations forgot to account for the four years of Augustus’s rule in which he hadn’t been called Augustus but had still gone by the name Octavian.

Further, the gospels don’t give a date for the nativity, but say only that it occurred during the reign of Herod the Great; however, Herod is reckoned to have died around 4 BC.

December 25th was also probably a simple case of co-opting the existing festivities around the Winter Solstice and the ancient Roman midwinter ‘Saturnalia’ that typically took place around that part of December and the celebration of the sun god, Sol Invictus. The first recorded date of anything like ‘Christmas’ being celebrated on December 25th was 336AD, during the time of Constantine, the first Christian Emperor and the source of Western Christianity, which for the most part was pretty divorced from Christianity’s Eastern roots or the historical Jesus of Palestine.

The portrayal of Herod the Great as a brutal monster is also a perfect example of this obvious 1st century propagandizing inherent in the narrative.

Scholars agree that there is pretty much no evidence to support the Matthew gospel’s story of Herod’s “slaughter of the innocents”. No Jewish or 1st century historians refer to any such incident. Even the contemporary chronicler Josephus, who is no fan of Herod and does refer to some of Herod’s cruel acts, makes no reference at all to the children being slaughtered. This story – which is now so embedded into the popular narrative – is largely regarded as having been invented in order to symbolically equate Jesus with Moses, again for the sake of appealing to 1st century Jews. Specifically it was designed to evoke the legend of the Pharaoh’s slaughter of all the first-born children of Hebrew slaves in Egypt; so Herod was the new villainous ‘Pharaoh’ and just like the infant Moses had escaped the slaughter, so too did the baby Jesus survive the mass culling; thus evoking the idea of Jesus being a Prophet with the perceived pedigree of Moses.

Less bias historians note that Herod, although he became increasingly paranoid and violent towards the end of his life (largely due to horrible and agonising medical conditions), had actually done a great deal of good for Judea and was one of the great builders of his era (including the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem).

But again, had Herod done something as brutal as ordering the slaughter of numerous infants, it would certainly be referred to in some historical source or another, not least in the writings of the very thorough Josephus who was a chronicler foremost of Jewish history during the Roman period.

But does it really matter?

In terms of outright demonising a historic figure like Herod, you could argue the gospel writers (or later editors) were being highly dishonest and unfair; but then, in reality, Herod was never particularly popular among the Jews anyway and was already long dead by the time the gospels were written.

Such propagandising goes on all the time even today in international politics (witness the mostly spurious Western media campaign against Gaddafi, for example). In terms of the other, broader fictions or propagandising in the Nativity narrative, it’s difficult to see that it really matters in religious terms, as the nature of the supernatural elements of the story demand a suspension of disbelief from the outset.

If you’re able and willing to embrace virgin births and raisings from the dead, for example, then it’s hard to imagine why you’d be concerned with historical minutiae.

Pure, unadorned fact is often a source of great disappointment, offering little encouragement or inspiration; and real history is broadly bleak and bloody. It’s in myth that people find the idealised visions and archetypes that most reverberate with our unconscious minds, as opposed to our logical processes.

The power of the Nativity narrative is in the power of imagery and mythology (and for some, faith), which doesn’t really require historical corroboration.

In fact, the very business of trying to reach for historical corroboration or academic validation seems both a losing battle and an ultimately unnecessary one, as even if a determined believer was to ‘prove’ the reality of the Roman census or the Star of Bethlehem, they would still be trying to prove the ‘historical reality’ of a story that ultimately centers on a virgin birth, angelic interventions and – later on – a bodily resurrection from death (and it *is* supposed to have been a bodily resurrection according to the mainstream religious interpretation – I’ve tried to suggest on occasion that it was meant to have been a spiritual or ghostly one, but have been repeatedly told otherwise).

No amount of pseudo-scientific theorising or historical research can prove those kinds of things, which are entirely matters of faith or personal belief. And personal faith or convictions, unlike attempts at historically or scientifically ‘proving’ the scriptures, cannot be weakened or destroyed by academia, science or historic facts, because they ultimately thrive at the subconscious, subjective or emotional levels of human psychology and not the intellectual.

It is precisely when people try to force a crossover *into* the realm of the intellectual that things start to fall apart.

The story of the Nativity, in all its richness and profundity, is not something anyone can intellectually justify believing in; but nor should anyone have to. Not should they even want to. As philosopher Simone Weil once argued, ‘The mysteries of faith are degraded if they are made into an object of affirmation and negation, when in reality they should be an object of contemplation’.

This shift from faith in or worship of the great mystery and the comforting story that early Christianity represented to the later, dogmatic and sometimes violent assertion of doctrine or ‘orthodoxy’ that characterises the less interesting side of Christianity occurred when the church itself became an authority with a power-base to protect and the need for expansion and domination (and therefore more power).

This was approximately the third century AD.

Prior to that, the Jewish communities that Christian beliefs originated from and then the earliest Christian communities themselves were scattered, persecuted people, often slave classes or lower classes, and the original gospel stories provided comfort, hope for the future (in this life and especially the next), a sense of self-worth and dignity, a sense of community, and much more.

The letters of Paul can be said to have done the same to some extent.

It didn’t matter in the slightest whether the texts were historically accurate or not, as their legitimacy as history wasn’t their purpose: their purpose was propaganda, uplift and inspiration. In some parts of the world, even today, it probably still serves those same purposes; especially where there is great poverty, oppression or persecution.

Unfortunately, like all religions that are later co-opted by institutions and states, the texts were eventually separated from their original purpose and character once ‘Christianity’ became an Establishment religion and a system of control and oppression in Europe.

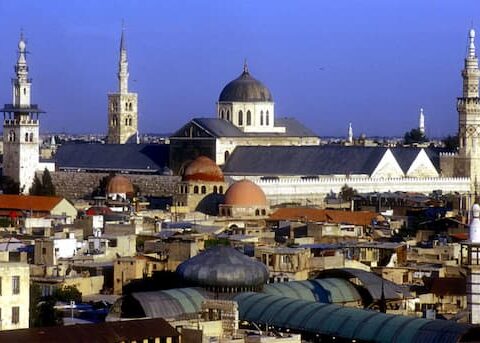

Yet in spite of all that, there’s something enduring, something evocative still in the popular version of ‘The Nativity’ that is still so much a part of shared consciousness, from the guiding star and the Three Magi (probably from Iran), to the animal-filled stable (which there is no reference at all to in any of the gospels) and Mary and Joseph travelling the wilderness by night to find a place to give birth. It is powerful as storytelling in general and as an item of faith and devotion for those who invest religious beliefs in it and even to many of those who don’t.

And I write this essentially as a species of non-partisan, agnostic ponderer; yet find the whole story of the Nativity entirely compelling, evocative and endearing, and have done since I was a little child.

But unlike that other enduring image of the Gospel narrative – specifically of the crucified Jesus – the Nativity story isn’t one that traumatises children or embodies pain and suffering; rather the opposite, it embodies a powerful sense of a new beginning, possibilities and promise.

Where the crucifixion narrative speaks to people about the injustice of the world, the cruelty of men and the corrupt nature of states, authorities and Powers That Be, the Nativity mythology conveys a mythic sense of hope, of a new, idealised world coming into being literally as a new life enters the world under magical, Disney-like circumstances.

There is little in our collective annals of history, mythology or religion, that has such a hold on the imagination as that scene does, with or without all of its theological connotations, to the extent that it can be said to transcend the problematic real-world definitions of ‘true’ or ‘untrue’, ‘real’ or ‘impossible’ and exist in a kind of bubble.

The fact that very little of what’s contained in the source material is likely to be *true* in the strictest sense is besides the point; the power of the myth has nothing to do with historical fact. The power of myths and mythical imagery is in the way they embody an idealised world that appeals to imaginations and speaks to some kind of deep-seated need that can never be met by a strictly real-world narrative.

At that deepest, unconscious level of human psychology, images, symbols and associations are far more powerful; and facts, semantics and the intellectual screening mechanism in general have much less power.

Which isn’t to say that the story conveyed in the gospels is *all* fairytale; it is almost certainly based on real-world events and real historic characters, though, given the amount of discernible embellishment, idealisation and propagandising also employed to frame the narrative, it is virtually impossible to determine the real history and reality (and the matter isn’t helped by the fact that there are precious few, if any, contemporary 1st century references to the historical Jesus). But it has always been the spiritual ideas, philosophical aspects, evoked sentiments and powerful imagery that have been most potent things in the gospel tradition and particularly the Nativity narrative; far more so than the dogmatic, evangelical or more offensive forms of Christianity or the mostly futile efforts to impart or affirm historical accuracy to the texts or even to try to couch miraculous elements of the stories into modern, scientific terms.

The problem is we now know far more about how the New Testament was compiled, how Western Christian doctrines were established, what other cults, ideas or religions influenced Christianity and the Hebrew scriptures before that; far too much so to be able to look at the old narrative with the same innocent, credulous eyes as people did even a hundred years ago.

We even have a number of highly convincing alternative models or theories forwarded by highly accomplished academics or researchers for what the gospel narratives and the Jesus story might’ve been about, including the Nativity story.

The question ‘Did any of it really happen?’ is actually very different to the question ‘Is Any of it True?’

Because ‘truth’ is such a complex, multi-faceted thing by nature. The influence of a thing, the ‘message’ it imparts or feelings it evokes, become a ‘truth’ in their own right, even if the thing at the source isn’t necessarily true or real. If people believe so strongly in an image or ideal or story and invest so much in it and draw so much from it, it attains a kind of reality that is independent from its root; so that, in effect, the idea becomes the reality and the historic event becomes almost irrelevant.

This has of course been the case with Christianity in general since at least the third century, because the theological construct of ‘Jesus Christ’ or the Isis-inspired transformation of Mary into the ‘Mother of God’ or ‘Queen of Heaven’ was clearly pieced together long after the fact and was determined in committees and councils with vested interests and was entirely disconnected from early Christianity or the real-world events that the original gospel authors were highly idealising in the first place.

Powerful and enduring imagery and symbolism that operates at the most unconscious level then becomes all the more important, because I imagine most practising Christians don’t mark Christmas in order to celebrate the creative powers of the early church fathers or the historical reality of an oppressive and violent theology and imperialist, expansionist Christianity that dominated Western Europe for centuries, nor the historical fact of the inquisitions, Crusades or Wars of Religion; but rather to mark, celebrate or draw inspiration from a powerful or comforting idea or ideal – separated and protected from the ugly real-world politics or history – with all its accompanying imagery and mystical connotations, regardless of whether it really happened that way or not.

The myth is always more powerful than the reality. The reality is impossible to prove, while the myth is impossible to tarnish or destroy.

And we shouldn’t mistake ‘myth’ for ‘untruth’ either, as myths are frequently based on real people or events, but are simply exaggerated, embellished or romanticised versions.

Predictably enough, it’s probably Joseph Campbell who summed up the power and importance of mythology best in various writings. “Mythology,” he once wrote, “is not a lie, mythology is poetry, it is metaphorical. It has been well said that mythology is the penultimate truth – penultimate because the ultimate cannot be put into words.”

Usually enjoy all your posts, but I think comments like most ‘objective academics’, ‘carefully measured propaganda’ means you’ve only read the most liberal of scholars.

Luke the Dr, Historian, private investigator writing in near perfect Greek! Have you read the gospel accounts? Have you read Luke and Acts, he is the author of both. How does Luke compare with the classical greek historians of his day…he is part of the 1%, so is Paul. How do the text compare with Herodotus for example? Luke went to Jerusalem with Paul (2 years), he had time to interview Mary et al, compare the writings available,as there were many, but how many were eyewitness accounts? Could proto Mark be trusted, as both Mathew and Luke used his short summary as the basis for there accounts. Matthew wrote to a primarily Jewish audience, Luke had a benefactor (Theophilis), John was a close friend of Jesus, and gave a completely different accounts, not using Mark.

Luke challenges the Imperial Cult of the day.

In Luke’s birth story, the key to seeing its political meaning is Roman imperial theology, which includes the divine conception of Caesar Augustus, the greatest of the Roman emperors and ruler when Jesus was born. He was conceived by the god Apollo in the womb of his mother Atia. His titles included “Son of God,” “Lord,” “Savior,” bringer of “peace on earth.” Inscribed on coins and temples, the public media of the day, they continued to be used by most emperors after Augustus.

Thus there was already a “Son of God,” “Lord,” and peace-bringing “Savior” in the world in which Jesus lived and in which early Christianity emerged. Roman imperial theology is the historical context for understanding the use of this language.

Luke’s story of Jesus’ birth is a primary example. It deliberately counters and challenges Roman imperial theology. It includes divine conception, and thus Jesus, not Caesar, is the “Son of God.” Mary’s song—the Magnificat—proclaims that the powerful will be brought down from their thrones, the lowly lifted up, the hungry filled, and the rich sent away empty (Luke 1:46-55). It climaxes with the message of the angel to shepherds: to them was born a savior, the Lord, who would bring peace on earth. But by a very different means—not through the power and domination of empire, not through the lords of this world, but through the way that Jesus was proclaimed and embodied. Early Christians saw in Jesus the alternative to an imperial world based on injustice and violence.

If you are trying to sell propaganda, why have women, shepherds (working class), Lepers, outcasts, The top man murdered in the most barbaric way, his mates run off, women on the scene to witness 3rd day, its seems utter nonsense…worth investigating further?

How do we judge historical accuracy in antiquity?

The New Testament is constantly under attack, and its reliability and accuracy are often contested by critics. If the critics want to disregard the New Testament, then they must also disregard other ancient writings by Plato, Aristotle, and Homer. This is because the New Testament documents are better-preserved and more numerous than any other ancient writings. Because they are so numerous, they can be cross checked for accuracy . . . and they are very consistent.

There are presently 5,686 Greek manuscripts in existence today for the New Testament.1 If we were to compare the number of New Testament manuscripts to other ancient writings, we find that the New Testament manuscripts far outweigh the others in quantity.

Author, Date Written, Earliest Copy, Approximate Time Span between original & copy, Number of Copies, Accuracy of Copies.

Try this:

https://www.amazon.com/Historical-Reliability-New-Testament-Evangelical/dp/0805464379

Any way, Really enjoy your work, keep it up in 2018.

Thanks, B. I totally accept and welcome your arguments, which I find entirely valid. I don’t think we can be categorical or absolute in our positions on any of this material.

The one additional point I would make, however, is that the volume of manuscripts or evidence in existence isn’t necessarily an argument in favor of the objective reality of the story told in the gospels – it is only evidence of the reliability of dating the texts and confirming the timelines, etc.

In other words, we can objectively prove what sort of time-frame the texts were being produced in and from that we can establish a sense of what was going on in a broad sense. But that doesn’t help us prove or demonstrate the objective ‘truth’ of the gospel narratives, concerning, of example, the Virgin Birth or the Resurrection. I would still argue that much or most of the texts are political and religious propaganda for the time – but that doesn’t negate underlying elements of the story being true.

At any rate, you raise very good points. And one of the reasons I love reading the gospels is that they present a perpetual mystery.

I am pretty mainstream in what I know … I’ve read some of the Dead Sea Scrolls but what interests me is the stuff that is canonical and how its power is exerted over us … a lot of it is still quite subversive … especially the parable of the sheep and the goats and not many churches live up to it although it is a statement that is basic to the teachings and example of Jesus.

Interesting … I’ve actually studied this kind of stuff and this is a generally accurate, accessible and evocative account. The Gospels must be read as products of very specific local groups with a very specific agenda … Mark writes badly and doesn’t seem to know what’s hit him … Matthew emphasises the idea of Jesus as fulfilling the Jewish scriptures … Luke is sucking up to the Romans … John is writing after the destruction of the Temple … Paul creates Christianity/Christology, works hard to spread the word and successfully keep the scattered communities on message. I was always told that Josephus’ mention of Jesus clinches it regarding the question of if he really existed as he had no vested interest in writing about him. Luke loves Paul. James gets the push and Peter becomes the rock … the Gospel of Thomas fails to achieve canonical status. Paul is kind of confusing, his writings are the earliest, he really pushes the point home about the universal Christ … there is neither Jew nor Gentile we are all one in Christ Jesus etc. … the Christian Anarchists love him. Nietzsche hated him, regarded him as representing the exact opposite of the teachings and example of Jesus. I lean towards Nietzsche’s view. Genesis and John, Exodus and Matthew. Isaiah and all of them? Fascinating when you know what the word midrash means and understand the Gospels as forms of Jewish midrash.

Thanks, NP, for such a good contribution and for bringing your own knowledge and understanding. It’s interesting you mention the Gospel of Thomas, which I’ve always found particularly interesting; I always feel Thomas should be Canonical, probably in place of John. The John Gospel has always seemed overly contrived and out of place, whereas Thomas would fit in nicely with the other three books.

Incidentally, have you read any of the Nag Hammadi library and those books?

Also are you familiar with any of the work of writers like Barbara Thiering on the subject of the ‘pesher’ codes?

Reblogged this on Lolathecur's Blog Below are two very important entries from the "Jewish Encyclopedia". Read them VERY CLOSELY..

Reblogged this on TheFlippinTruth.