To mark Easter Sunday, I’ve decided to pay respect to a largely forgotten film that no one ever talks about, but that I think is utterly worth mention.

That film was called The Greatest Story Ever Told; a 1965 Biblical epic produced and directed by George Stevens.

Now first off – I’m not big into Biblical films and I tend to dislike overly evangelical works of any type. In fact I resent any art that is really just sneaky evangelism masquerading as something else and I’m instinctively turned off when anything gets preachy. There’s a reason Biblical films have been so out-of-favor for decades now, the social and cultural climate having (rightly) changed very much since the hey-day of the Biblical Epics in the fifties.

The extremely divided reaction to Passion of the Christ highlights exactly why Bible-inspired films are so outdated and represent a hornet’s nest that no studio really wants to put their hand anywhere near. In addition to that, most Biblical films are really, really bad; embarrassing dialogue, awkward performances and uncertain tone are often the problem, along with the fact that such films unavoidably come across as ‘having an agenda’.

The Greatest Story Ever Told, however, was made almost 50 years ago, at a time when Biblical epics were virtually guaranteed box-office gold in Hollywood; they were the superhero adaptations of their day, with Jesus the Peter Parker of the era.

Some of them were really bad; I mean really bad – even worse than Passion of the Christ. And they almost all had Charlton Heston in them. I’ve watched a lot of them, largely out of a fascination with the old ‘historical epics’ (Ben Hur, Cleopatra, etc), which the Biblical films tend to get rightly or wrongly lumped in with.

However, some of those big films of the time still hold up even now; I still find The Robe, starring the one and only Richard Burton, enjoyable even though a lot of it is very silly, and I still enjoy watching Barabbas with Anthony Quinn (a film about the criminal pardoned by Pontius Pilate in place of Jesus), despite being a highly flawed film; while Ben Hur remains one of my favorite films of all time, though in many ways it’s not really a Biblical film.

The Greatest Story Ever Told isn’t overall as good a film as, say, Ben Hur. It’s a lot better than the terrible King of Kings, which came out a few years before it and starred Jeffrey Hunter (Christopher Pike from the pre-Shatner pilot Star Trek episode) as Jesus. And it’s also a lot better than pretty much any Gospel-derived film endeavour that’s come since, all of which have been basically unwatchable (with the exception of the Jesus of Nazareth mini-series in the late 70s, which, though suffering many of the same weaknesses as other Biblical adaptations, had some notable strengths).

However, the reason I hold up The Greatest Story Ever Told to be one of the best films ever made has nothing to do with its themes, the Gospel narrative, or its script; the script in fact is quite bad in large parts, much of the dialogue overly evangelical, as you’d expect in a film depicting the life of Jesus.

No, what’s utterly masterful about this film is the cinematography. Visually, this film is just stunning.

Scene-for-scene, the direction, the lighting, every detail, is utterly arresting, utterly absorbing, and this was all long before CGI days. This is an extraordinary example of a film that looks pretty bad on paper yet becomes something truly marvellous on the screen.

I first discovered the movie about eight years ago during a lazy morning some time around Christmas; I was captivated by it and have watched it at least once every year since, just like I do with films like Lawrence of Arabia.

One time I even watched half of it with the sound off because the dialogue was annoying me and I just wanted to see it, experience it visually.

I’m not going to enter into the pro-CGI versus anti-CGI debate, but the argument that excessive computer-manipulation detracts from the ‘authenticity’ or ‘reality’ of the finished film becomes particularly interesting when you watch a film like this that is so visually compelling, so immaculate, yet was accomplished entirely the old-fashioned way. In an age when there were still serious limitations on what could be done on screen, The Greatest Story still represents some remarkable visions being fulfilled through the artfulness and creative innovations of the time, in spite of technical restrictions.

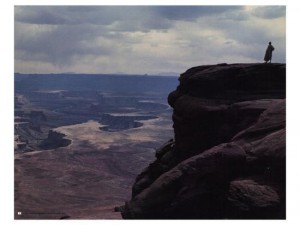

Two additional directors were ‘informally’ brought in to aid George Stevens – Jean Negulesco and the legendary David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, etc). And Stevens commissioned French artist André Girard to prepare 352 oil-paintings of Biblical scenes to use as storyboards. That particular detail is interesting but doesn’t surprise me, having seen the film; a number of scenes, particularly wide-shots and stunning panoramas, feel like evocative paintings being translated into the medium of film.

The Greatest Story Ever Told contains some of the finest, most memorable shots you’ll ever see in anything.

I may even be willing to go on record as saying that, purely in terms of cinematography (and in no other sense), this might be the greatest film I’ve ever seen.

Some examples of extraordinary scenes? The one that stands out most is the scene of Jesus’s temptation in the desert. Having just left John the Baptist, Jesus climbs a mountain in the desert as day turns to night; as this is happening, we can still hearing John’s preaching echoing across the desert from the Jordan. Jesus enters a high cave and in there he encounters an old man we immediately know to be the Devil. A subtle, downbeat version of the temptation ensues.

What’s extraordinary about this scene is how it looks.

The appearance of the night sky blanket in the background is beautiful, illuminated by a mesmerizing, oversized moon that remains in-shot for the entire scene. There’s an unreality to the way the moon looks throughout all this, which just subtly indicates the possibility of the encounter itself having an element of unreality to it. The entire thing is visually stunning, but aided also by Donald Pleasance’s understated portrayal of the Prince of Darkness.

That scene is one great example of the film’s visual brilliance. But examples are scattered throughout the picture.

The event of the Raising of Lazarus is another good example. Aided by a superb score, this depiction of a crucial scene in the Gospel story is memorable for several reasons, one of them the fact that we never actually see the raised Lazarus; rather we see the reactions of all the witnesses to the miracle. What the scene as filmed does is capture vividly the sense that all these people watching on have witnessed something extraordinary, something unspeakable; but without ever showing it.

Before all this unfolds, however, the build up to the scene is so quiet, the vast quietude and isolation of the desert setting being captured marvelously.

There are numerous other moments of equal quality; the lighting and tone, for example, of a simple scene where Jesus and his apostles are sat by the Lake of Galilee, creates a genuinely spellbinding aesthetic, so vivid that it makes you feel you’re sat by the water and you can feel the richly-coloured sunlight and when one of them tosses a pebble into the water you can almost feel an imaginary splash-back.

“Are men like circles in the water…?” the same disciple asks. “Do they just float away… and are lost?” he asks, regarding the execution of John the Baptist.

These sorts of effective, understated moments occur several times over the course of the film. I think it’s this understatedness, this refrain, that aids the film a lot too. Contrast this to, say, The Passion of the Christ, which is all about exaggeration, excessive histrionics and deliberately magnified brutality and villainy; the Greatest Story…, on the other hand, is quiet and decidedly unspectacular. It’s all about the aesthetic nuances and the sense of more being communicated somehow in the artistic silences than in the actual dialogue.

It’s as if this film doesn’t need to overly announce or explain anything, it just shows it; this is in contrast to, say, the King of Kings, its Biblical-epic rival, which actually needs Orson Welles’ narration in order to transition from point to point in the story.

By the time shooting was completed on Greatest Story... in August 1963, George Stevens had amassed six-million feet of Ultra Panavision 70 film (about 1829 kilometres or 1136 miles). The budget ran up to an astounding 20 million dollars.

The film was a commercial failure, falling significantly short of even being able to break even. It received a lot of negative reviews too; and even to this day is often rated poorly. One of the major criticisms of the film at the time was it’s inability to connect with audiences. And in truth, yes, there is an aloofness to the film and the performances and it probably doesn’t elicit much of a connection or identification.

All of that is fine; like I said, the film has weaknesses, I don’t claim it to be amazing on every level. It is somewhat more esoteric in style than other Biblical films and that was bound to alienate the majority of its audience; but for someone like me watching it five decades later this is actually one of its strengths.

As a work of art, this movie ages a lot better than other films of its genre.

Aside from that, there are also other strengths to the film. Alfred Newman’s soundtrack is superb, for one thing. I’ve mocked the script, but actually some of the dialogue in places is quite good depending on the character; so Herod dialogue, for example, is usually compelling, as is anything ‘The Dark Hermit’ says, whereas most of what is put into the mouths of Jesus and especially John the Baptist… not so good at all.

Max Von-Sydow’s Jesus is more than watchable, though some critics saw his performance as wooden. But Jesus is a virtually impossible role to play for any actor; there’s nothing you can do with that role except just try to play it straight. I’ve seen a number of actors try to play that role – Jeffrey Hunter, Christian Bale, Jeremy Sisto – and none of them were very good at it. It’s a toss-up between Von-Sydow and Robert Powell’s depiction in Jesus of Nazareth as to who’s managed the best Jesus on-screen portrayal.

The two standout performances in this film are, for that matter, Donald Pleasance as the Devil (though he’s referred to in the script only as “the Dark Hermit”) and Jose Ferrer as Herod Antipas. Pleasance almost seems born to play the Prince of Darkness; it’s very understated, ‘Satan’ portrayed more as a scruffy, mean-spirited old man than anything else. But there’s a specific shot of Pleasance’s character watching from the shadows as Judas is hurrying off to betray Jesus,which is just haunting – you’ll never see sheer meanness of spirit so vividly expressed and entirely without dialogue.

And Jose Ferrer is superb as Herod Antipas – he’s the real scene-stealer in this film, his performance again understated and somewhat Romulan. Herod Antipas in this film is portrayed as simply a pragmatist, someone tiredly goaded into taking certain actions that make him the historical villain, largely because he is a man living very much in the shadow of his father Herod the Great.

While it presumably wasn’t the filmmakers’ intention, Ferrer’s portrayal of Herod is so sympathetic and Heston’s John the Baptist so annoying that you end up on Herod’s side for most of it (or at least I do) – but I imagine it wasn’t written to be that way.

David McCallum also deserves mention as Judas Iscariot; he portrays Judas beautifully, making a genuinely sympathetic character, someone we can understand and feel sorry for. In particular the scene in which he explains why he’s handing over Jesus is beautifully acted; and again, like most of the film, is a visually compelling scene, appearing in almost literal darkness.

Other performances aren’t so great, one of the worst being Charlton Heston’s as John the Baptist, as already mentioned; it’s just never believable, and unfortunately he gets lumbered with most of the worst, most irritating dialogue. This is always a problem with Biblical films. But a particular failing in this movie, as pointed out by critics at the time, was that there were just too many famous faces cropping up and distracting from the integrity of the story; Sidney Poitier, Shelley Winters, Roddy McDowall, John Wayne even shows up as a Centurion (!).

Filling a movie with overly famous cameos only serves to undermine the illusion and is never a good idea in a work of this type. John Wayne is the worst, but Telly Savalas as Pontius Pilate was always a bad idea (no, ‘Kojak’ a Roman Procurator does not make), though Martin Landau isn’t too bad as Caiphas, and the film also has roles for Star Trek legends Michael Ansara and Mark Lenard.

The film is also noted for featuring the final performance by Claude Raines (as Herod the Great) before his death, this in fact being one of the scenes known to have been directed by David Lean.

But as I’ve said already, the acting isn’t what this post is about.

Again, on a technical level, this film is extraordinary; it is a masterwork. Loyal Griggs and William C. Mellor, responsible for the brilliant cinematography, were deservedly nominated for the Academy Award in that category, with Art Direction and Special Effects also being categories the film was recognised in.

It’s extraordinary to watch a film that I actually don’t like very much in key respects, yet absolutely adore as a work of cinematography.

It leaves me in the strange position of being unable to say whether it’s even a good film or not; only that it should be watched, particularly by people who are interested in the art of film itself.

I mean, watch it on ‘mute’ if you have to; but just watch it.

That concludes this Easter Sunday sermon. Go in peace, brethren.

Reblogged this on TheFlippinTruth.

Yes I always look at the treatment of Judas and the portrayal of the religious and imperial authorities in general.

A sympathetically-written Judas is always a good sign. So is a non-supervilain-like Herod, but a more human king with psychological complexities.

Yes that scene was very well done … better than Scorsese’s take for sure but his Judas is better imho?

No, I liked this Judas in TGSET. He was very textured and sympathetic, very human; as contrasted to the Mel Gibson version of Judas, for example, where he may as well have been a comic-book villain. I also really like Ian McShane’s Judas from ‘Jesus of Nazareth’ – have you ever seen that series?

No but I probably will have soon … I have an obsession with popular depictions of Jesus. Unless it was the BBC mini-series from a few years ago where the resurrection was treated very ambivalently? Like in the meeting on the road to Emmaus?

No, this was from the late seventies. It’s very famous; every actor who ever lived was in it… Robert Powell, Peter Ustinov, Anthony Quinn, Laurence Olivier, Christopher Plummer, Ian McShane, James Earl Jones, the list goes on and on. It was a tv mini-series. Probably the best depiction of Jesus to date, acting-wise. Definitely look it up when you’ve got time.

I know it … Robert Powell was the face of Jesus in my youth … the title ‘Jesus of Nazareth’ ticks one of the right boxes for me but I haven’t seen if for a while.

Worth re-watching. It’s a bit too evangelical in tone, but some of the drama is fairly well done.

I tend to be obsessed with depictions not so much of Jesus, but of the support cast of historical characters, particularly Herod.

I agree that it is visually stunning but although I have watched a lot of films I cannot put the cinematography into the context of film criticism. It seems to me that the Director/Artistic Director tried to blend a whole range of Christian images, doctrines and music. There were parts, especially ‘The Last Supper’ where the influence of Da Vinci, Caravaggio and Rembrandt was apparent and they did a good job of it. Handel/Jennens didn’t get a credit for the Hallelujah chorus either!?

Oh and by the way, I think all stories about Jesus should end at the point of death … including, and perhaps most especially, those in the New Testament.

Isn’t the resurrection supposed to be the whole point, in religious terms?

Ok, with ‘Handel/Jennens’ you’re getting too high-brow for me now! What matters is that you watched the whole thing based on something *I* said. Which makes me feel incredibly powerful all of sudden 🙂 At least you agree it’s visually stunning anyway. The fact is, however, no Jesus film and no film based on religious scripture is ever going to be particularly good: the medium and the subject just don’t go well together.

Handel wrote the music and Jennens the words to the bit that goes … ‘King of Kings (forever and ever) and Lord of Lords (Hallelujah, Hallelujah) di do di doooo …’ I agree that it does not make a good script for a film and in comparison to other Jesus films I’ve seen it actually stands up quite well. Eclectic with a capital ‘E’ basically. Do you agree about the Caravaggio like scenes?

Yeah, I agree with you about the Caravaggio evocations. A lot of the scenes were set up like paintings; like stills. It’s really evocative and memorable. As for Handel, yes I think I know the scene you’re talking about now; it’s the Raising of Lazarus scene, right? Which was a really powerful scene, the way it was done.

Goodness me this film is nearly as long as one of your posts … what I saw of the cinematography was stunning but I fell asleep and woke up at the intermission. I’ll let you know what I think of the overarching narrative of the film once I manage to watch it all!

Please do, NP: you’ll be the only person on earth I can actually have a discussion with about it, as no one I know has ever seen it or has any intention of ever watching it! By the way, I take great offense at ‘nearly as long as one of your posts’: how dare you! 🙂

Well maybe it is better with the sound turned down!? Perhaps they could have had a more convincing ending too? It should end at the exact moment of Jesus’ death.

Probably true. I didn’t say it was a great film in general terms; I said it had amazing cinematography. What did you think of it visually, aesthetically?

Well … a lot of people could do with watching that! lol

Can’t say I am that familiar with this film but I’ll give it another watch soon. I totally agree about Gibson’s ‘Passion of the Christ’ where I found myself in the strange position of wanting to walk out because it is a meaningless and let’s face it rather anti-Semitic film but didn’t because I thought the packed cinema would think I was averse to the remorseless gore which might actually have redeemed itself by leaving out the empty tomb bit. Pasolini’s ‘The Gospel According to St. Matthew’ is near the top of my list, as is Scorsese’s ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ but somewhat ironically I honestly believe that ‘The Life of Brian’ is the best Jesus film ever!?

The Life of Brian isn’t a Jesus film though, is it? It isn’t that the point – that it’s not about Jesus at all? 😉 I love that film too though, of course – though I always thought ‘The Holy Grail’ was even better Python film. Yes NP, definitely check out this film again and watch it on a purely cinematic level to take in how extraordinary it is. If you can overlook John Wayne playing a Centurion, that is 🙂 ‘The Gospel According to Matthew’ as a film – I’ve never even heard of that!

It’s on YouTube with EN subs GAtSM if you’re into films I think you will like it … You’re right about ‘The Life of Brian’ but I suppose I just meant that it has all the bases covered and more about activism/religion/politics than the most serious attempts to explore those questions through reference to Jesus who does appear in the film at least once and Brian gives simplified statements that could have come from Jesus? I’ve only seen ‘The Holy Grail’ once and ‘The Meaning of Life’ 2 or 3 times … I’m sure I’d get more out of them than I did when I was in my twenties.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=77K8iQTVsHc

Thanks, NP, I’ll check that out. Speaking of the Life of Brian, am I the only one who wants to show ISIL and all the different Syrian rebel groups the ‘People’s Front of Judea’ scene 🙂 ?

Reblogged this on theburningbloggerofbedlam.