In Lauren Bacall we lose one of the very last surviving icons of a long-gone age in cinema, an era that many still regard as cinema’s richest.

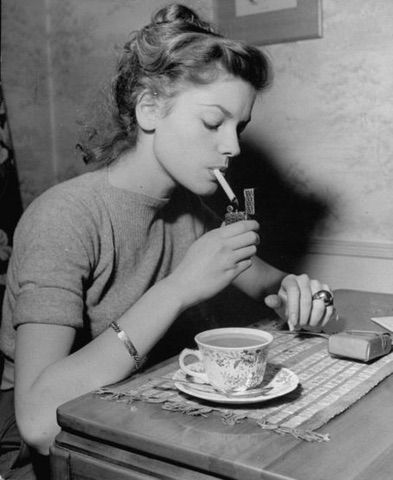

An era that still holds so many memorable, iconic performances and images that echo down through the generations of cinema and culture; the image of Lauren Bacall in black-and-white film, with her intent, ice-cool look and with compulsory cigarette between fingers, being prime among them.

In fact I remember when I was younger and long before I properly knew who Lauren Bacall was, seeing an image of her from the forties and having it make a real impression on me and stay with me; just from the quality of the photography and the sheer aesthetic impact of her appearance.

Then when I did see The Big Sleep years later I had that revelatory moment of realising “Hey, it’s her!”

There’s that ongoing idea people have of “famous people always dying in threes”; I always try to pooh-pooh that myth, but often it does seem to happen that way. While the majority of tributes and focus at this time will probably still be on the more tragic Robin Williams, I hope the passing of Lauren Bacall doesn’t get too overlooked.

Even as someone aware of her cultural relevance and her body of work and as someone who has considered himself a fan, I’ve only barely scratched the surface of her film career, which has been a long and prolific one spanning several decades. The Big Sleep (1946) and Dark Passage (1947) remain incontestable classics and are the blue-print of film noire in Hollywood.

That The Big Sleep is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, crime drama is pretty much beyond question. And it is also beyond question that Lauren Bacall was one of the six or seven primary screen icons of her time.

I also managed to watch How To Marry a Millionaire some time ago, in which Bacall starred with Marylin Monroe in 1953, and 1957’s Designing Woman with Gregory Peck. Beyond the actor she is most associated with – her first husband Humphrey Bogart – Bacall collaborated on-screen with many of the greatest stars of cinema due to the rich, star-laden era in which she herself began her very young career; yet despite that it is unlikely she was ever outshone, as her own substantial screen presence from very early on made that difficult.

In modern cinema we associate that sort of ‘screen presence’ with older, more accomplished actors (Alec Guinness, for example, or Peter O’Toole or Richard Harris, or the older Katharine Hepburn – a great friend of Bacall’s – in the later stages of her career, or even more modern examples like Morgan Freeman) and it’s rare that a young or ‘rising’ star has that kind of aura or is capable of ‘out-presencing’ their older, more accomplished co-stars; but Lauren Bacall, strangely most associated with her earliest film roles in which she was very, very young, had that rare screen presence.

She seemed to have arrived on screen fully-formed with her own distinct style, method and ‘brand’ (I hate using that word, but I can’t think of a better one).

It lent itself, like all iconic “brands”, to copying and to parody (it’s not just anyone who gets caricatured in a classic Warner Bros cartoon short; earlier this year she also appeared in a recent episode of Family Guy, which might’ve been her final major appearance). But it’s often been said of Bacall’s look that she wasn’t classically pretty like Rita Hayworth was or an obvious ‘sultry’ sex-symbol like Ava Gardner, but that it was more about her particular ‘way’, her manner and her style.

Its influence across the decades has been evident in, among others, Lana Del Rey and Uma Thurman. Uma Thurman could almost be Bacall’s sister, such is the resemblance; I always got the impression that Tarantino would’ve cast the younger Lauren Bacall in Pulp Fiction if such a thing had possible (not that Uma wasn’t brilliant in that film).

Her singularly cool demeanor, trademark look and style and distinctive voice are virtually an institution in American film and it’s hard to think of anyone else with a more iconic on-screen image or ‘brand’ (again for want of a better word) as an actress. In actual fact, far from being a contrived trademark, this distinguishing characteristic came about as a response to intense nervousness; the story goes that during screen tests for To Have and Have Not, Bacall was so nervous that, in order to minimize her quivering, she lowered her chin against her chest and faced the camera with upward-tilted eyes.

It became known thereafter as “The Look” – Lauren Bacall’s trademark and more broadly one of the most enduring images from across the reels of cinematic history.

In fact whenever I think about that era in cinema, the image of Bacall in trademark film-noire setting is one of the very first things that comes to mind, along perhaps with the unforgettable image of Rita Hayworth in Gilda. For an individual actor’s style or performance to resonate that far beyond its original time is an extraordinary accomplishment, particularly in the context of our modern culture of quantity-over-substance and generally short-lived impact.

Just as much as her husband and co-star Humphrey Bogart, her distinctive style, look and persona holds an enduring quality that can justifiably be called ‘classic’ in the truest sense of that over-used word.

Particularly with a cigarette between her lips, it has to be said. Along with actresses like the aforementioned Ava Gardner and Rita Hayworth, she made cigarette smoking look like the most stylish affectation imaginable, this being back in a time when there wasn’t the stigma associated with it (nor, in many cases, the awareness of the health issues; a substantial number of the stars of those couple of generations went on to die of cancer or smoking-related diseases when they were older).

I was recently going to write a post on the ‘coolest cigarette smokers ever’, but then decided it was a bit irresponsible (even though I’ve been a cigarette smoker myself for about sixteen years and just recently switched to e-cigarettes); but Lauren Bacall was going to be third on that list only after Gardner and then Bogart himself.

She made cigarettes look so ridiculously cool and sexy. Smokers nowadays don’t have that same aura; maybe we’re too medically and socially aware.

But I can’t think of a more captivating, more romantic and debonair image than a black-and-white shot of a Lauren Bacall or Ava Gardner with a cigarette between their fingers or their lips.

I mentioned her distinctive whiskey and cigarette stained voice, and earlier I mentioned it’s not just anyone who gets immortalized in a Warner Bros Merrie Melodies cartoon; there are not many movie stars who get a medical condition named after them either – Bogart–Bacall syndrome (BBS) is a voice disorder that is caused by abuse or overuse of the vocal cords, and from which both she and her former husband were considered to suffer.

Lauren Bacall wasn’t just a vapid Hollywood starlet either, but a highly intelligent, politicised figure who could appeal to the sensitivities of someone like Germaine Greer (here’s a link to an interesting piece Greer wrote concerning Bacall several years ago) on the one hand while serve as a role model for a young wannabe movie star or glamour-seeker on the other.

Like such cinema giants as Orson Welles, she was one of the staunchest opponents of McCarthyism in Hollywood in the fifties (as was Bogart, both of them being passionate liberal Democrats).

She was outspoken and articulate, and just like the characters in her most classic forties film roles the real Lauren Bacall could come out with thoughtful, succinct quotes. Epochs later in a 2005 interview with Larry King, Bacall reaffirmed her long-lasting position as a staunch “anti Republican”.

“A liberal,” she said, “The L-word. Being a liberal is the best thing on earth you can be. You are welcoming to everyone when you’re a liberal. You do not have a small mind.”

There is in fact television footage from the sixties that I recently saw, which showed Bacall being interviewed in the wake of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination and saying basically that the America she believed in was ‘finished’. It is evident that Bacall did not have any kind of rose-tinted view of the America she was living in; and was in fact an incisive social and political commentator.

Most of her scattered film and TV roles beyond the fifties consists of things I haven’t seen; I’ll have to do some catching up some day, but that’s always the case when you’re trying to retrospectively appreciate the work of someone whose primary career occurred decades before you were born (I’ve been trying to do that with Peter Ustinov and Charles Laughton and isn’t easy, being very time consuming). I haven’t seen 1996’s The Mirror Has Two Faces, which is considered her last great performance (and for which she won a Golden Globe and was nominated for an Academy Award) and it’s something I’ll have to make time to watch, nor am I versed in her theater work

There is an issue with Golden Age film stars that while we might love to watch them in their prime in those old movies with their air of aged romanticism, we sometimes hesitate to watch them as much older actors in later roles.

The inimitable Katharine Hepburn, a close friend of Bacall’s, seems to be an exception to that, but I struggle to watch Audrey Hepburn for example in her later roles when she was older; perhaps it reminds us too visually of the realities of ageing and mortality.

Perhaps we want to keep people like that preserved in a certain time with a certain image or aura. The same is probably true of Lauren Bacall; it will probably remain her early film roles that she is most remembered for. “Legends are all to do with the past,” she once said, “and nothing to do with the present.”

Like the brilliant Peter O’Toole, who died in December, she had to be eventually awarded an Honorary Oscar to amend the oversight of her never having received one in her career, despite nominations.

She is probably the last survivor of those highly iconic film stars from what many still regard the Golden Age of Hollywood, although unlike say Elizabeth Taylor who died three years ago, Bacall never seemed to have much regard for the institution of ‘stardom’ or ‘Hollywood royalty’ despite her intimate association with the likes of Humphrey Bogart and Frank Sinatra; like Rita Hayworth she seemed, on the contrary, to harbor a disregard for such notions or trappings and that was clear from the tone of her later interviews in which she always seemed far too intelligent to have ever been caught up in the notions of stardom or celebrity that were highly prevalent then and are horribly prevalent now.

“We live in age age of mediocrity,” Bacall was quoted as saying in a much later era.

She once joked that her obituary columns would be littered with Bogart references; I hope that’s not the case, but that she is credited and remembered on her own merit.

Having said that, being something of a (slightly damaged) romantic, I like to think that she and her old flame might be due some manner of otherworldly reunion as we speak; if so, he’ll have been waiting since 1957.