The passing of Peter O’Toole in December 2013 was a sad moment for me.

I had a strong personal affection for the man and his work, stemming primarily from my undying love for the film Lawrence of Arabia, which I consider a contender for the greatest movie ever made.

But, such was his length of career and diversity of work, that my first lasting impression of O’Toole was when I was six or seven year-old kid watching the 1984 Supergirl movie, in which he played ‘Zaltar’. It was hardly his shining moment of greatness nor something critics are likely to ever draw attention to. But as a kid I loved him in that movie.

And it is somewhat perverse that the actor who was at the center of one of the greatest cinematic masterpieces in film history, and who mesmerised people on stage in Hamlet or King Lear, could also be known to a dumb little kid in the 80s (like me) primarily as ‘Zaltar’ from Supergirl.

I still stand by Supergirl as being a terrific movie, by the way.

It wasn’t until about 10 years later that I saw Lawrence of Arabia for the first time and was utterly mesmerised by both David Lean’s extraordinary film-making and by Peter O’Toole’s extraordinary screen presence.

Prior to that – and still being a youngish kid – I had also seen O’Toole in the comedy movie, King Ralph, which was the only other thing apart from Supergirl that I knew him for. Though mostly forgotten, King Ralph is still a fun – if stupid – little movie.

But when I first saw it, I remember shouting “that’s Zaltar!” And my Uncle saying, “That’s Peter O’Toole – don’t you know who Peter O’Toole is?’

I didn’t.

But I would find out in due course.

He was an unknown when David Lean cast him in Lawrence of Arabia, the film that turned him into an overnight superstar. Remarkably, Marlon Brando was the original first choice for that iconic role – which is now frankly impossible to imagine happening.

But what an epic performance; it has long since become not only iconic, but timeless and even something that could be described as almost transcendent and otherworldly.

There are few performances in the history of cinema, even great performances, that could really be described in those terms.

One also wonders, however, if such an iconic role and performance so early in his film career might’ve created almost a Citizen Kane like scenario, with O’Toole spending the rest of his career in its shadow.

Peter O’Toole’s body of screen work is a strange, scattered one, not necessarily filled with numerous box-office hits as you might expect from an actor of his stature, but with varied and textured performances and a highly diverse span of films, ranging from such extremes as 2008’s poignant Venus at one end to something like the animated hit Ratatouille at the other.

He was in some pretty bad films too, it has to be said; but such was his presence that he became “the only good thing” about a number of otherwise terrible movies, as “great presences” tend to be.

And the reason I’m posting this article now is because I just recently re-watched the wonderful Lion in Winter and was freshly reminded of how great a screen presence O’Toole was and how fascinating a cultural icon of the twentieth century. And that I had intended to write a big tribute to him when he died a couple of years ago, but had never gotten around to it: and had instead just posted a quick list of my O’Toole memories.

There is, of course, also a lot to be said for O’Toole’s stage career as well; which was probably more important to him than his screen legacy, it has to be said. It is a great regret that I am too young to have had any chance to see O’Toole do Hamlet or King Lear, as it must’ve been mesmeric.

The week of O’Toole’s death I downloaded a full recording of his acclaimed stage performance in ‘Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell’ and it was compulsive viewing; the man, by now white-haired and elderly, had me glued for the full length of the show in one sitting.

Beyond his stage and screen career, O’Toole was legendary for his ‘hellraiser’ days and his personal life.

He may not have suffered the Oliver Reid style full-on meltdowns on live television, but the stories about O’Toole’s antics are endless; including stories about driving into the backs of police cars, assaulting off-duty police officers, and, um, smuggling antiques through customs in his foreskin.

That he went on benders is an understatement. He lost entire sequences of days.

His long marriage to Siân Phillips (who, whatever else she may have done in her career, has achieved eternal immortality for her stunning portrayal of Livia in I Claudius: fun fact – O’Toole played Livia’s son, Tiberius, in the film Caligula) was said to be strained and pretty tumultuous. After getting married, instead of holding a reception, they apparently went on a pub crawl instead.

He is said to have lavished her with gifts, including priceless Etruscan jewellery (which he may or may not have smuggled in his foreskin), which she complained should’ve been in museums and not in her personal property.

And much of O’Toole’s life during the prime of his career was characterised by the stories of wild drinking and raucous behavior. He is said to have drunk so much that he would fall asleep during stage performances. During the filming of Lawrence of Arabia, he had been assigned a minder by David Lean.

Alec Guinness later wrote, having observed O’Toole’s behavior at formal events; “O’Toole could have been killed – shot, strapped or strangled – and I’m beginning to think it’s a pity he wasn’t.”

Someone I used to know once told me about witnessing O’Toole in a pub in Central London in the mid-70s; “he was a total prat”, he told me. He and Richard Burton in fact did much of their drinking together – something which supposedly stopped only when Elizabeth Taylor found them both drunk on the floor one night and forbade Burton from hanging out with O’Toole anymore.

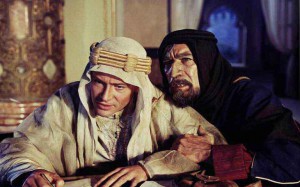

During the Lawrence days, O’Toole also established a life-long friendship with Omar Sharif, who at the time was also about to made an international star by the movie. During this time, O’Toole and Sharif once flew to Beirut and blew nine months’ wages in one night; while in another incident, they apparently solicited sex in a nunnery (mistakenly thinking it was a brothel).

The fact that O’Toole and Sharif, both young men at the time of meeting (during Lawrence), would retain a lifelong friendship is one of the more endearing anecdotes from the annals of cinema. They remained friends well into recent years and O’Toole continued affectionately to call Sharif by the name “Fred” – because, going back to their very first introduction, O’Toole had supposedly said “Omar Sharif? NO ONE could be called Omar Sharif! Your name is Fred.”

In an interview not long before his own death, Omar Sharif said that O’Toole was his only on-screen colleague that he ever retained a lifelong friendship with.

Of course, reading about his personal life or antics has nothing to do with what I loved about Peter O’Toole and is superficial – even if it is particularly entertaining.

It is interesting, however, that O’Toole never really became the great raconteur in his older years in the way that say, Richard Harris did, or more classically the likes of Orson Welles and Peter Ustinov.

In a way, however, this also allowed him to retain a greater degree of mystique.

I read the first of O’Toole’s recent(ish) books, Loitering With Intent: The Child – which chronicles his childhood in the years leading up to World War II – just shortly before his death and with fascination, and found myself wishing he had written more. O’Toole, like Richard Burton, had long held literary ambitions and a desire to write poetry. Unlike Burton, however, O’Toole seemingly was never embarrassed or regretful about being an actor.

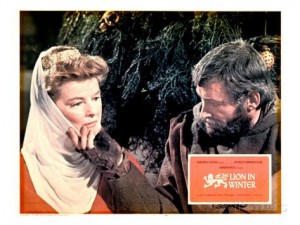

Watching O’Toole and Richard Burton in Becket is almost an overload of on-screen charisma and gravitas, but O’Toole reprising the same role four years later to star opposite Katharine Hepburn in The Lion in Winter is even more so: The Lion in Winter – for which Hepburn won an Oscar and O’Toole yet AGAIN was snubbed – remains one of the greatest cinematic instances of two film giants chewing scenery and engaging in an epic dialogue duel.

Some of his most remembered screen performances remain oddities or great spectacles, such as in How To Steal A Million’ with Audrey Hepburn, or his ‘eccentric’ (wasn’t he always eccentric?) performance in ‘The Ruling Class’.

He also showed his comedic capabilities in, for example, Woody Allen’s What’s New Pussycat? (1965) in which he shared the screen with Peter Sellers. There are often undercurrents of comedy in even some of his serious performances (such as his central role in the largely forgotten TV mini-series Masada – which I chose to talk about here); suggesting that he could’ve been a significant comedy performer had he sought to go more down that road.

Peter O’Toole doing full comedy in his prime is something I wish we had access to. He would’ve made for a great Pink Panther cameo – just as his friend Omar Sharif did.

I also maintain that O’Toole – had he ever been offered it or been interested in it – would’ve made an absolutely sublime James Bond. In fact, had O’Toole been a late sixties or seventies James Bond, he would’ve completely owned that brand and no one would talk about Sean Connery or Roger Moore.

For all his stature as an actor and all of his Oscar nominations over the years, O’Toole was famously the most nominated actor to never win an Academy Award. In the end, the perceived injustice of this had to be remedied by the Academy giving him an honorary award for his contribution to film. How O’Toole’s Lawrence performance didn’t garner an Oscar is probably the greatest mystery in the history of that institution.

How great was O’Toole? Where does he stand in the all-time pantheon? It’s largely subjective, of course; but he has to be up there with the best of the best.

In reality, his filmography doesn’t necessarily reflect his god-given talents all the way through – but whose does?

Just Lawrence alone guaranteed him permanent cinema immortality before his career had even properly started. And when you add Lion in Winter, Becket and some of the other key films he starred in, he clearly becomes without question one of the great screen presences in all film.

And for all that, his primary love and what he is probably the most highly regarded for was his stage work and not cinema at all.

But when I think of O’Toole, the one image – more than any other – that seems to sum up his life (both on screen and off) is that image in Lawrence of him holding up the lit match to his eyes, a playful, devious smile on his face, and blowing it out: and the extinguished flame instantly cuts to the shot of the sun rising over the desert.

That same romantic, and classically David Lean, image is what I most thought of when O’Toole died too. A lit match being extinguished, and also a sun rising to signal immortality.

I have to say one more thing. Watching BECKET all I can think of as I study him is “he is a king. How does he know how to be a king, that King? I was enthralled.

That summed up my feelings about O’TOOLE as well as anyone ever could. When I got to see him I was struck like I was witnessing a miracle his screen presence was so utterly fascinating.

I too never understood why he never won an Oscar. It’s quite hard to believe that in Lawrence he was an unknown, a newcomer. How could he be when he so belonged there. I only wish I could have seen just some of his stage work. I’m sure I would have been speechless.

I’m so glad to read that there’s someone out there like me who revered this beautiful actor.

Thank you.

Thanks so much, Roberta. If you look on YouTube, there might still be a full recording of his one man stage show ‘Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell’. It’s great.