2014 marked three decades since the death of Richard Burton.

But aside from being a mesmeric screen (and stage) presence, Burton also remains an engaging, enigmatic figure himself. So what is it that remains so engaging about Richard Burton this much time after his passing?

Some critics famously regarded Burton as an archetypal example of a tremendous talent failing to live up to his full potential. Many had immensely high expectations of him, which they judged him as having failed to meet. This was a strange situation for any actor (or artist in any field) to be in; most actors merely have to contend with the difference between favourable and unfavourable reviews, not have the hopes or expectations of critics riding on their career moves.

Yet this was what Burton contended with.

Many criticised him going to Hollywood at all and saw his journey into big movies as somehow a betrayal of his roots and a cheapening of his true talents; in others words, they judged him too good for Hollywood.

It didn’t help that, as superb and as lauded as his performances in films like Becket (extraordinarily bringing us a cinematic team-up of both Burton and Peter O’Toole) and the endlessly compulsive Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (probably the most compelling of his movies with Elizabeth Taylor) some of his film choices turned out not to be great ones, and some even of his worthwhile projects ended up as both critical and commercial failures; The Comedians (1967), Boom! (1968), and the Burton-directed Doctor Faustus (1967) all fell into that category. Even the lavish Tudor epic Anne of a Thousand Days (1969) was a commercial failure, though not a creative one necessarily.

He was judged by many to have been almost a real-life Faust who had sold out to Hollywood at the cost of his true calling.

This view of him was so blatant at times that he was even confronted with it openly by interviewers, leading to one particularly memorable instance where Elizabeth Taylor angrily came to his defense, answering on his behalf when Burton was asked about his artistic integrity in a television interview. A very uncomfortable looking Burton seemed equally as uncomfortable with his wife answering on his behalf as he did with the nature of the question in the first place.

Looking at some of Burton’s writings as well as his interview footage, it is evident that this external pressure from critics, this sense of expectation around him and the sense of disappointment in his career path, affected him. At one time the highest paid actor in the world, he was the classic troubled, brooding, psychologically complex actor caught in a struggle between perceived artistic integrity on the one hand and wealth and success on the other, the subject of probably the most glamorous ‘celebrity couple’ of the twentieth century on the one hand and yet someone who wanted to be taken seriously as a performer on the other and who genuinely cared about his craft.

In some ways a Kurt Cobain of the Hollywood age.

Watching him being interviewed can therefore be both very interesting and a little uncomfortable, as he seems very uncomfortable a lot of the time, like someone not happy in their own skin. In the interview with Michael Parkinson shown above, for example, he talks candidly about things like his alcoholism, having a death wish, the idea of suicide; it’s hard to imagine most modern celebrity film stars being able to do that (or being allowed by their managers or agents to do so), but Burton was of a different time and class and the talk-show format used to be more conducive to that kind of interview than it is today; a point I touched upon in this piece about Sir Peter Ustinov.

But how would someone like Burton even fare in contemporary cinema?

Well, he would certainly have little problem on stage, particularly in the kinds of classic Shakespearean theatre productions he was renowned for; but on screen its likely Burton’s style of acting wouldn’t be sought out by producers and directors anymore, the modern standard of screen acting being firmly based on the Brando-style method-acting at the best instances; or artless celebrity ‘film star’ casting at the worst.

You couldn’t imagine him being happy frequenting some of the ‘big name’ fluff movies that Hollywood studios put out; one tends to think of some of the awful films that Peter O’Toole ended up being in the later stages of his career, projects that really were beneath him.

But even at the higher end of things, that Thespian, stage-crafted style of strongly-projected, larger-than-life acting is considered hugely out of fashion, entirely quaint in modern cinema and television.

Perhaps precisely because it’s something we associate with the past some of us tend to romanticise that style of acting and those old movies.

I’m way too young to have gotten to see Burton on stage unfortunately, so all I have is his screen work to go on. And he himself would probably hate to hear this, but his version of Mark Antony in Cleopatra remains one of my all-time favourite film performances. It’s also Burton’s Mark Antony that remains the definitive portrayal to my mind, and that’s even including James Purferoy’s Antony in HBO’s Rome.

But contrasting these two portrayals of the same historic character highlights exactly why someone like Burton would be uncastable in most contemporary productions. Purferoy’s Antony is all about a harsh, realist depiction of what the real historical character would’ve probably been like in the genuine historic setting; Burton’s on the other hand was all about that timeless, romantic vision of a great (though flawed) heroic lion of history. Someone like Purferoy could never do what Burton did in Cleopatra effectively; and it’s questionable whether Burton could do that gritty, real-world version of history either. It highlights the differences in film-making vision and ideals in one age as contrasted to another, and with it the difference in what productions sought from their leading actors in the different eras.

Which is not to comment on which is ‘better’, of course; both being valid approaches.

Burton never considered himself a good screen actor, his talents far more suited to the stage.

He even acknowledged that he learnt a great deal about how to act on camera through observing Elizabeth Taylor’s naturally quiet, understated approach. Burton might’ve learnt to adapt his style to suit modern cinema; after all, others like Richard Harris and Peter O’Toole were able to continue appearing in even Hollywood productions for many years (Harris’s portrayal of Marcus Aurelius in Gladiator being especially memorable), so perhaps Burton would’ve been able to do the same.

Having said that, in making that transition it’s likely that everything that was so compelling about Burton’s performances would be lost; so maybe it’s better that never did happen.

Burton, it is clear from his recently published diaries, was losing his enthusiasm for acting anyway, considering it as “pansyish” occupation. It’s likely that, had he lived longer, he would’ve retired from the profession anyway. Perhaps he was very much a performer for his era and we should be glad he was there in that era, given the platform he had to express himself.

The shame of it is that he doesn’t have the greatest or most consistent screen filmography and some of the major roles he is most known for weren’t ones he was particularly proud of. I wonder sometimes if the nostalgia for performers like Burton and O’Toole necessarily means we’d want to see their stage-style acting make a return to big film productions.

We probably don’t; it probably wouldn’t coalesce very well with modern filmmaking.

It probably does belong in the past, where it can be appreciated in all its glory and natural context.

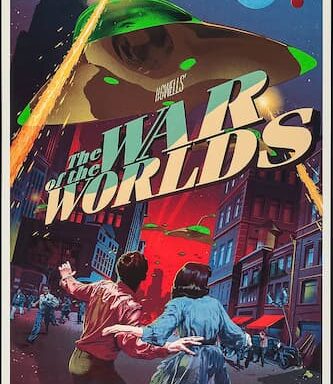

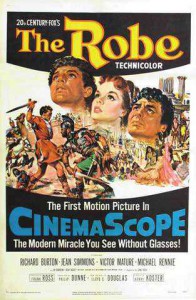

There is still something slightly magical about those old big-scale productions too, such as Cleopatra and The Robe, both starring Burton. They were very flawed films in numerous ways (particularly The Robe) and if I was to review them as a critic I wouldn’t legitimately be able to laud them as masterpieces; yet even so they manage to maintain a hold on the imagination. I find myself re-watching Cleopatra almost once a year, mostly for Burton’s Antony (though Roddy McDowell’s Octavian is something special too); if they were to remake that film now and with modern cinema sensibilities there’s no way it would have that same magic or attain that timeless quality.

Nor would it find a lead actor able to breathe the kind of unforgettable life Richard Burton did into history.

____________________