“…in spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death…”

“…I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquillity will return again.”

So wrote Anne Frank in one of the most moving passages of her diaries; a sentiment that, despite the horrific experiences she was witness to at the time, still contains that surviving trace of youthful hope and optimism for the future.

A hope and optimism that, in her case and in the case of millions of others, would never be requited by reality.

And ‘reality’ is very much the point; we live in an era where the further we move away in time from the events of the nineteen thirties and forties the more the reality of what occurred in Europe is in danger of being obscured by myth or blunted by the overabundance of literature, film-making and rhetoric on the subject.

Also the simple, inevitable dampening effect of the passage of time might serve to erode away some of the reality of those events, particularly in the minds of people who weren’t born when those things were occurring (such as myself) or who have no personal link or sense of connection to those events other than that of common humanity.

Today is Holocaust Memorial Day and is also the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp by Russian troops in 1945. Survivors will lay wreaths and light candles at the so-called Death Wall at Block 11 to mark this 70th anniversary and to remember the well-over-a-million human beings who were coldly and industrially murdered at that unspeakably grim location.

As some news commentators note, there won’t be many more anniversaries left when the young will be able to hear from people who saw these events with their own eyes and experienced them with their own bodies and souls. The remaining Holocaust survivors are the last living witnesses to the most heinous atrocity of modern history and their stories will soon pass from the more powerful realm of living testimony and into the drier realm of recorded history.

The number of surviving eye-witnesses continues to diminish with each year: there were still some 1,500 a decade ago, with reportedly now only around 300 in 2015. One wonders what will happen once they are no longer with us; whether the harrowing events they testify to will become even further obscured or objectified to young or future minds.

Whether, for that matter, the trend of revisionist history or Holocaust Denial might grow further.

As far as revisionist history goes, some of this trend towards re-examining or re framing history is very valid: such as, for example, looking at the role of Zionist collaborators in the extermination of the European Jews or at how the plight of the Jewish populations was used for geo-political ends (such as the creation of the modern State of Israel).

All of that stuff is valid and important: there are more layers to the story of the Nazi genocide in Europe than is generally expressed in mainstream discourse and history.

Where I entirely draw the line is at actual Holocaust Denial – which, aside from being incredibly insulting, also has very little basis in fact. You could quibble about numbers – but there’s no legitimate question that millions of civilians were exterminated in Nazi Europe.

I was exposed to the classic The World at War series when I was young and although I didn’t understand all of it, some of the distressing imagery and the basic message always remained with me. I’ve watched the whole series at least twice again as an adult, along with a number of other documentaries and films on the subject, as well as numerous books on the Holocaust and on the Third Reich. And yet I still sometimes forget the ultimate *reality* what was allowed to happen, still sometimes lose the true human sense of it to the facts and figures.

Young people should be asked to watch something like The World at War as part of their history or sociology education at school; they need to understand where the evils of dehumanization and the ills of human nature can ultimately lead.

They need to know the dangers of mass hysteria too and of being subject to state propaganda and to mass conformity.

What remains the most compelling thing about something like The World at War is the interview footage of concentration camp survivors, people who’d lived in Nazi Europe, both Jews and ‘Aryan’ Germans alike, as well as other people caught up in those events. That living link – being able to see people’s faces, their eyes, their demeanors, and hear the nuances in their voices, when they give their accounts – is incredibly affecting, affording a more palpable reality to the history they’re testifying to than can be gleaned from a written text.

Most, probably all, of those interviewees and eye-witnesses are deceased by now.

I once met an elderly man who had survived not Auschwitz but Dachau. I never asked him about it. I only knew about that aspect of his past through a third party. But you could see it in his face and in his demeanour; that there was something there, something so unspeakable, so profound, that I would never be able to understand the true reality of it. I doubt anyone could, except for those who experienced it. I have at least one family member also who was friends with a (now deceased) Polish Jew who’d survived Auschwitz and lived the rest of his life in London; and that old man did talk about it to him, did tell him one or two stories of his experience; stories that made my hair stand on end when they were relayed to me years later.

I’ve always found it interesting that also two of the other friends I’ve had at different points who were from traumatic, war-torn countries – one from Kosovo, the other from Sierra Leone – were both cheerful, incredibly friendly people. I always found that strange; always imagined, I suppose, that people coming from that sort of environment would be more hardened and embittered.

Differences of opinion will continue as to the exact number of people liquidated by Nazi Germany in the Holocaust; but the accepted academic view is that of the nine million Jews who lived in Europe before the Holocaust, an estimated two-thirds were annihilated.

Millions of others, including the disabled, the Romanies, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, communists, socialists, political enemies of the Third Reich, and political Catholics were also slaughtered.

The Nazis sent at least 10,000-15,000 homosexuals alone to concentration camps where they were forced to wear pink triangles.

When I mentioned earlier the ‘overabundance’ of literature, film and rhetoric on the subject of the Holocaust, I’m not suggesting of course that the subject shouldn’t be explored and interpreted at length; but simply observing that when there is such an abundance of such material, many become over-fed on it and almost lose touch with the underlying reality – and all that it means and represents – and cease to remain as disturbed by that reality as they might have been in the first instance. Even the term ‘Holocaust’ and terms like ‘The Final Solution’, along with images of Hitler and the Nuremberg Rallies or imagery of the concentration camps themselves, are so much a part of the shared language and so embedded into the collective consciousness, that it’s easy to sometimes become numb to the reality – and I refer to the ‘reality’ not in the academic, matter-of-fact sense, but in the felt, human sense.

In many ways the problem is that this reality is difficult to fathom.

The numbers of those murdered are too great for us to really comprehend or make sense of. And both the scale and the nature of the evil committed is too big to process intellectually. Thus the language that some people fall into when describing the events of Nazi Europe or the Holocaust is often highly academic, with reference to numbers and statistics, dates and facts; which are of course important, but it sometimes masks the nature of just how dehumanised the concentration camp victims were.

They were murdered in the most systematic, industrialized manner conceivable, and this combination of highly organised, regulated genocide and unfeeling disregard for life may be the most disturbing real-life horror story in all of history.

But the sickness and cruelty went beyond the mass liquidation itself; for example, British troops liberating Bergen-Belsen found that the Nazis had been using (their victims) human skin for lampshades. There were manners of depravity being acted out with a casualness that is difficult to equate with reality; human beings, including millions of children, treated like animals (and in many cases worse than animals).

The dehumanisation aspect of what the European Jews were subjected to remains extraordinarily harrowing, no matter how many books you might read, how many documentary films you might watch or exhibitions you might attend.

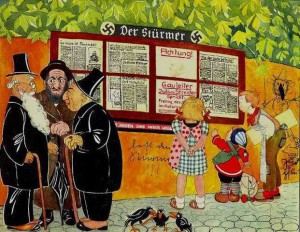

It is surely dehumanising a person or a people that is the first step to enabling their maltreatment (or in this case, their extermination). In Nazi Germany this was built up over time, with the Jewish population being not only vilified but heavily and relentlessly caricatured and made the object of ridicule through anti-Semitic cartoons and the like.

In first dehumanising a race or type of people (accomplished through concerted propaganda and indoctrination), they are relegated to ‘sub-human’ and ‘unworthy’ even of life, much less of respect, dignity or compassion, and can be treated literally like cattle in a slaughterhouse, herded about naked and shaven-headed, robbed of all human identity or dignity, and disposed of in groups, their possessions and even parts of their bodies retained for re-use and redistribution as if they were mere factory-line components.

Even as I type that sentence and these words, I feel like I’m undermining the reality of what I’m referring to – just by the very process of trying to put it into words.

Which is part of why listening to the testimony of living survivors of the Holocaust remains so important and so powerful; a ‘warning from history’, as one famous documentary series once put it, concerning where it is that racism, hatred and lack of compassion can ultimately lead. These links are to particularly poignant examples of Holocaust survivor stories and recollections recently published to mark this anniversary. But there have been many more over the decades of course; some famous like Viktor Frankl, Primo Levi, Dr Jacob Bronowski and Elie Wiesel, and many more others privately endured and undisclosed to posterity.

And every time you start to think you’ve read or heard every story, every distressing or poignant human tale or damning, dispiriting testament to Mankind’s capacity for evil, you come across some new personal story or account that reminds you that there are just too many stories and that the sheer scale of the horror is just too vast to be able to comprehend.

In this piece from The Independent, survivor Tadeusz Smerczysnski, now 91 years old, relates how his day “is wrecked ” if he hears anything from the opera Tosca on the radio. It reminds him of the afternoon in Auschwitz during which he heard the strains of one of the opera’s arias coming from a camp barrack room.

“The SS just went in and shot him – just for singing. He was the star tenor in the Brussels opera. His entire family had been gassed that morning.” Smerczysnski goes on to say, “I don’t believe in God. I’m just glad that most of today’s generation have not had to experience what I did.”

Muselmann (the German for “Muslim”) was slang for concentration camp victims who had relinquished any hope for survival. These inmates would apparently squat with their legs tucked in an ‘Oriental’ manner, their heads dropped in despair. The renowned Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi once said that if he could encapsulate “all the evil of our time in one image, I would choose this image.”

Heinrich Himmler, head of the murderous SS, ordered the evacuation of all camps in January 1945, charging camp commanders with “making sure that not a single prisoner from the concentration camps falls alive into the hands of the enemy.” Believing that a reconciliation with the West might still be possible, Himmler wanted to eliminate all evidence of what the SS had been doing.

On January 17th, 58,000 Auschwitz detainees were evacuated under guard, largely on foot; thousands of those who hadn’t yet been liquidated in the death camps then died in the subsequent ‘death march’.

One of the most bitter stories from those days at the Reich’s end (they’re all bitter) concerns how, after the various concentration camps had been liberated, thousands of people who had been starved, beaten and worked to the point of exhaustion died within their first week of freedom. This included some who even died from over-eating sweets and chocolate provided by soldiers, having been starving and malnourished prior to that.

The fact that just this month we’ve had Far-Right rallies going on in Europe reminds us that the reality of Nazi Europe is already being either forgotten or no longer regarded with as much disdain by certain sections of otherwise sophisticated societies.

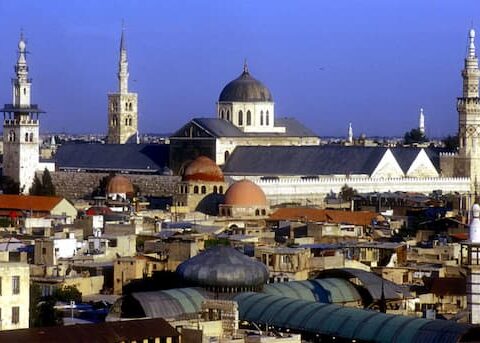

Which is possibly what starts to happen when the generations that lived through the horrors of the past begin to die out. Think about it: this 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz takes place not only against a backdrop of resurgent anti-Semitism in Europe and elsewhere, but it comes against a backdrop too in which anti-Muslim feeling is rampant and growing in Western societies, leaving the minority Muslim communities feeling just as threatened, having already felt marginalised by anti-Muslim propaganda for years now.

In some societies, particularly Germany (of all places) the “anti-Islam” rallies have garnered great attention, with many seeing the rise of the Far-Right and intolerance as a serious concern in terms of the direction things might be going in in Europe. As if that wasn’t enough for connotations, senior Pegida figure Lutz Bachmann, a driving figure behind the anti-Islam rallies, was recently ‘outed’ dressing up as Hitler, as though that association is just a minor joke (or worse, something to be proud of).

What the mainstream historical narrative often fails to remember is the lack of sympathy or care from other states or nations for the plight of the Jewish communities in Europe. As Jews fled Hitler’s Europe, representatives from Great Britain said it had no room to accommodate Jewish refugees. The Australians said, “We don’t have a racial problem and we don’t want to import one.” Canada said of the Jews that “none was too many.” Only the Dominican Republic offered to take 100,000 Jews, but their relief agencies were so overwhelmed that only a few Jews could take advantage of the offer.

Prior to World War II, and particularly prior to those first, disturbing images emerging from the liberated concentration camps, there clearly wasn’t much sympathy for the European Jews despite their desperate situation.

But it can happen in any time, any century. In the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and yes, in Europe again.

The idea that we’ve all learnt from history or understood the reality of Nazi Europe’s crimes (and I keep saying ‘Nazi Europe’, because it’s too easy and too lazy to blame Germany alone when several other countries were complicit in the mass genocide too) can be seen to be false.

If that were true, there would have been no ethnic cleansings in the world beyond 1945, but that hasn’t been the case.

And we live now in a very unsettling time and climate in which race-hate, insidious propaganda and even war-crimes are on the increase and in which human life is again being objectified and cheaply treated. We are in a time again where races, religions or cultures are being vilified and demonised based on stereotypes or skewed propaganda (the amount and the nature of both anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim propaganda to be found on-line is astonishing in this day and age). And in which renewed and heavy militarisation is occurring on various fronts.

If ever there was a time when societies in general need to be reminded of the realities of Nazi Europe and the Holocaust, it is now.