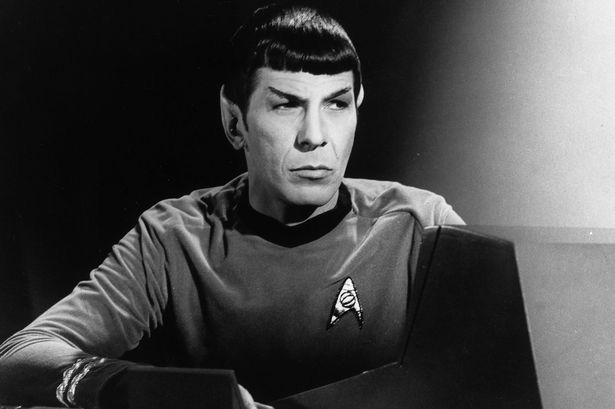

It’s hard for people sometimes to explain why someone mattered to them; someone they’ve never met, that is. Someone they had no personal relationship with. But Leonard Nimoy’s passing is one of those that hits you in a very felt way.

I still also remember how surprised I was by how upset I was at Deforest Kelly’s death many years ago, but it taught me how significant a part people like Kelly and Nimoy do actually play in our lives. Since then, the advancing years of both Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner have always been in the back of my mind, so though I haven’t been caught off-guard by the news of Nimoy’s passing, it’s still a marked moment; in which one of the great pillars, one of the great gods, of our childhood or our collective cultural edifice departs off beyond the Great Barrier to whatever lies beyond.

It’s because people like Nimoy and Shatner, through their immortal and mythical alter-egos, are people we do actually have a personal relationship with; they are part of our lives in that they are part of our inner-lives, part of the deep landscape of our consciousness and part of our mythologies – and what more personal a relationship could there be than that, you might ask? The same could be said for the relationship many people have had with say Luke Skywalker and therefore Mark Hamill, to cite another popular example.

Those characters are part of our eternal landscape both in a broader cultural sense and in a more personal, individual sense too.

I remember my very first experience of Leonard Nimoy and of Star Trek itself; aged about six or seven years old I watched the TV premiere of The Wrath of Khan. I remember vividly watching Spock’s death scene for the first time, his heroic self-sacrifice, and then that poignant, emotional final farewell between him and Kirk, the famous “I have been and always shall be your friend” scene. That scene embedded itself in my consciousness so much as a child and stayed with me for so long that it may actually be my defining fictional representation of both friendship and death (as it probably is for a lot of people). Seriously, if I had to pick any on-screen exploration of death and mortality that remains the most stirring, Spock’s dying in Star Trek II comes absolute top of the list, with all its accompanying themes of regeneration, rebirth, ageing and lost youth, friendship and devotion.

Now that I’ve just heard the news of Leonard Nimoy’s passing, I can only think of that permanently evocative scene of Shatner’s quivering lip as Spock’s burial tube is being launched out into space and into the literal place of rebirth. If I was to watch that scene now, given today’s sad news, I would definitely shed a major tear; but actually whenever I watch that (and those) scenes I get a lump in the throat anyway.

I tend to watch The Wrath of Khan and its sister film The Search For Spock once every year, because those films are special to me and because they speak so powerfully, so epically, about life and death and the big, ineffable, indefinable issues, struggles and mysteries of existence. I only recently covered that subject in this post about the third Star Trek film, which Nimoy himself directed, so I won’t rehash all of that here. Even listening to the epic James Horner soundtracks for those two films has that effect on me, both for how extraordinarily good the music is and also for all of the thematic and emotional associations; and Spock’s death and life are at the center of those themes and its Nimoy we most think of therefore.

I’m not sure I could even handle the emotional punch of those two films if I was to attempt to watch them any time in the next few weeks, given Nimoy’s real-world passing. For that matter, his ‘passing the torch’, father-figure type role in the modern Star Trek reboot now perhaps take on even more poignancy; admittedly I didn’t entirely enjoy seeing him in those films, purely because I didn’t like watching him as such an older figure; which ironically plays back into the very themes that make those two older movies so poignant – ageing, the life-cycle, death and how we react to them.

Watching the repeats of the Star Trek: Original Series as a kid, admittedly it was Kirk I loved most as a child, but even then I fully understood that Kirk, Spock and McCoy were in essence inseparable; that the three of them together were what made that show so superb.

I’ve never personally got the whole sex-symbol thing as far as Spock is concerned (but then why would I?), though I was fascinated to read, via Nimoy’s own writings, about how iconic the character (and Nimoy) was for the late sixties counter-culture zeitgeist. Gene Roddenberry was even famously told by NBC execs to “drop the Martian”, which once again shows how clueless most execs are when it comes to creative vision.

Some younger than me probably don’t realise just how famous Nimoy when I was a kid and how much his character and its franchise was all-pervasive in the culture; not just the TV series being permanently re-run or the big-screen releases, the merchandising, books and collectibles, but the loving satire and parodies of which there were so many, even the (admittedly terrible) pop songs and the like. Someone a few years ago bought me a CD called ‘Spaced Out: The Best of Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner‘ for my birthday, thinking I would love it. The CD features all of the pair’s various pop-song exploits, from Beatles’ covers to Nimoy’s ‘Ballad of Bilbo Baggins’. It’s awful; all of it is awful.

And I must’ve listened to it thirty or forty times, because it’s so awful that it becomes entertaining; and because it’s Nimoy and Shatner, for God’s sake. Who else but Nimoy and Shatner could have us wilfully listening to such awful music and enjoying it?

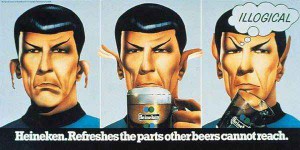

I also remember seeing those famous Heineken billboard ads from the eighties, being possibly the only adverts that have ever gotten a reaction out of me in probably my whole life; for weeks I’d be yelling out ‘Look, there’s Spock!’ to my parents in the back-seat of the car every time I saw one. Sadly, even though I was a whole six or seven years old by then, my parents wouldn’t buy me any Heineken (even though Spock said it was alright).

I also notice at various times how much of ‘Spock’ there is in me, and also in one or two of my friends and people I’ve known over the years, the same being true for a few other classic Star Trek characters over the years (McCoy, Odo, Rom, one or two others). I’ve often wondered if it’s because fiction reflects reality or because we are significantly influenced as we grow up by the characters we spend our time watching and we take some of their characteristics on board on an unconscious level.

It’s a strange thing, but when I think of ‘people’ who’ve most influenced me in terms of my personality, thinking and traits as I’ve grown up, it is rarely real-world people but more often mythical or fictional figures; Nimoy’s Spock certainly being one of them.

I was talking to someone quite recently about the extent to which our modern, shared mythologies form a huge part of the cultural, even moral or ethical, framework of our lives because they’re such an embedded and such a rich point of reference; the way that people of older generations referred to Bible stories and characters or religious stories, for example, is the same way people like me, and (I’ve discovered) some of my closest friends, refer to our modern mythologies like Star Trek, Star Wars, or, for me also, things in old comic-book mythologies, among other examples.

I’ll talk about Luke Skywalker in the Dagobah swamp trying to decide whether to confront his father the same way someone else might talk about Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemene.

Or I’ll think about some Kirk or Spock moment the same way; for example, the noble self-sacrifice Spock makes in The Wrath of Khan to save his ship-mates or the incredible level of platonic love and devotion Kirk displays in Star Trek III in order to rescue Spock’s “immortal soul” from its place of death.

I’ll refer to or draw upon mythical events like those the same way more religiously-inclined people draw upon scripture.

That’s getting into the famous Joseph Campbell/George Lucas level of modern myth-making and mythology and their power over us. The point being that someone like Nimoy and the fictional character he played then go far beyond mere ‘acting’ or ‘television’ and into a level of cultural relevance, both at the broader, shared level and at the smaller, personal level, that is frankly extraordinary.

I’m not sure if Nimoy himself would’ve even been aware of that level of effect; though given his interaction with fans over the decades, it’s possible he was. That is an immensely powerful legacy to leave behind; a cultural immortality of the most powerful kind and that very few performers or artists in any field get to lay claim to.

I was very sick once and actually for a few weeks or more was thinking about my own mortality for the first time in a serious way. When I was in that state and finding it very difficult to find any meaning or comfort in anything, it wasn’t religion or traditional spiritual ideas (even though I’d been raised in a significantly religious, albeit multi-faith, background) I found myself turning to, but it was genuinely the first three Star Trek films more than anything else.

I don’t know how our collective culture will develop in the future of course, but it seems to me that our modern mythologies have become far more powerful than they were ever intended to be; this is something I recall hearing George Lucas talk about once or twice, though he seemed to regard it with some negativity. I’m not regarding it as negative or positive, just as fact.

In the recent article I posted about the third Star Trek film, I wrote; ‘You can’t have watched films like this when you were a child and not have developed a long-term affinity; with their evocative, dual scientific and spiritual motifs, the refrained emotionality and emotive heroism, these films become a permanent part of your consciousness, seeded in childhood and growing with you as you age. And particularly as you start to experience some of those themes in your own life experience; at which point these films start to resonate even more.’

‘These characters and their epic struggles are to us what the Epic of Gilgamesh must’ve been to young Babylonian men as they grew up or what the Greek demi-gods or Roman myths must’ve been to their respective enthusiasts within those cultures. Every culture, every generation, needs its heroes, especially flawed ones, and needs its mythologies.’

People like Leonard Nimoy and Mark Hamill – and I keep using Mark Hamill as a comparison because he, like Nimoy, felt he had his acting career ‘suffer’ from being too associated with a specific, iconic character – may not have had the kind of diverse or long acting careers they once wanted, but they achieve a true immortality by being such significant figures in our shared mythologies. A Tom Cruise or a Will Smith may have long, highly lucrative film careers and scores of big, hyped roles, but it’s highly doubtful either of them will acquire the sort of long-lasting cultural immortality that someone like Leonard Nimoy, or for that matter William Shatner, has.

As with many actors, there is often a resentment a performer has for a pop-culture role that they become too associated with and that comes to define them.

Nimoy certainly felt that way for a long time and was open about his resentment; but did entirely come full circle. I still have my old copy of Nimoy’s I Am Spock biography from 1996 (a follow-up to a much earlier I Am Not Spock book) – a Christmas present from my Mum at the time. I haven’t read it for a while, but will probably end up re-reading in these next few weeks. I highly recommend it to fans (along with Star Trek Creator: The Authorised Biography of Gene Roddenberry by David Alexander, which is a remarkable insight into Roddenberry’s life), as it provides a fascinating insight into the life of both Nimoy and his Vulcan alter-ego and in many ways represents Nimoy having come to terms with both his fame and his inexorable association with the character that had made him so famous.

It was always discernible that Nimoy, more than Shatner, wasn’t all that comfortable with fame and preferred to keep his distance. After a certain level of fame, he seemed to prefer to work away from the limelight, focusing on directing, writing, photography and his other passions.

Meanwhile the recent Star Trek reboot, which unlike a lot of ST fans I actually think are very good as entertainment, showed that you can effectively and successfully recreate, re-imagine and amplify something like Star Trek, but that you can’t replace someone like Leonard Nimoy. Zachary Quinto’s Spock is perfectly watchable, of course; but he just isn’t Nimoy. Because no one can be Nimoy; a role as iconic as that and as deeply associated with one actor as that role is cannot be replicated.

In his 1996 memoir, I Am Spock, Nimoy first writes as ‘Spock’ and then answers as himself the following. Spock: ‘Live long and prosper…’. Nimoy: ‘I’ve already done the former, and thanks to you certainly done the latter’.

Leonard Nimoy is Spock, as he said himself in his book. They could remake Star Trek for the next hundred years, but there will only really have been one Spock and that’s the first. That is a manner of immortality that most people, and most actors too, can only dream of. Because the fact is that Star Trek is so permanent a part of our shared culture that people are still going to be watching Leonard Nimoy’s Spock a hundred years from now, the same way we still watch Chaplin.

Leonard Nimoy is and will remain one of the immortals, a permanent feature in our lives, our shared points of reference, and on our screens.

___________________

LISTEN TO THE BURNING BLOGGER/MUMRA 2K PODCAST TRIBUTE TO LEONARD NIMOY HERE.

___________________

A beautifully written post, one I found hard to read through my blurry eyes.

Thanks Mumra 🙂 For anyone reading, Mumra and I recorded a podcast on the night of Leonard’s passing – it will be available on this site some time in the next couple of days.

Leonard Nimoy will be missed, may his memory be eternal††† I remember when I was young I did not call it Star Trek, I called Mr. Spock.

It’s remarkable how pervasive his character and the Star Trek mythology is, involving all types of people, every part of the world, every age group and generation. Thanks JRJ.