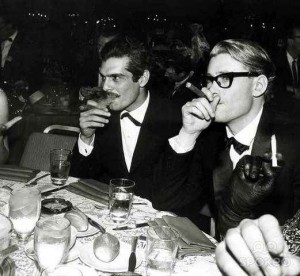

“Omar Sharif…? No one is called Omar Sharif! Your name is… ‘Fred’!”

That was what Peter O’Toole said to his then unknown co-star the first time they were introduced, on location filming what would become a legendary film, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’.

And true to his word, O’Toole continued calling him ‘Fred’ for the decades that followed; the two actors had remained close friends right up until O’Toole’s death in December 2013.

Legend has it that the two of them got themselves arrested on their first night in Hollywood.

The 1962 epic, Lawrence of Arabia, was the breakthrough film role for both actors. For O’Toole it was the beginning of his cinematic career and it made him an immediate star; for Sharif, it was the role that brought him to Hollywood and to Western fame, having previously been a star of Egyptian cinema up until that time.

David Lean had cast Sharif in the movie because he’d wanted ‘authenticity’ to the Arab character who was to have the most screen time; this was especially desirable as the two other key Arab roles had already been filled by veteran American and British screen stars, specifically Alec Guinness as Prince Faisal and Anthony Quinn as the tribal chief Auda Abu Tayi.

Sharif proved perfect for the role and, as Sharif Ali, he became an unforgettable part of an unforgettable film.

From that point on, Omar Sharif was not only a star in his own right, but remains essentially the only significant Western film star of Arab origin; and once David Lean had turned to him again, this time to play the lead role in Doctor Zhivago, Sharif was elevated to ‘leading man’ status and guaranteed a place in film history for playing key roles in two of the most important films of the twentieth century.

Doctor Zhivago is of course another David Lean masterpiece; though I return to this film a lot less than I do with Lawrence, it is without doubt one of the abiding cinematic monuments.

The extent to which Doctor Zhivago became so entrenched into culture and popular consciousness was largely linked to the amount of time it remained in the cinema, allowing people to go see it months and months after its initial release. It wasn’t, in financial terms, a success at first; if it were judged in today’s cinema context of ‘opening weekend profits’ or box-office stats, it would be judged a catastrophic failure.

But in those days a movie had much more time to draw in its audience and build up a reputation and a level of popularity. And cinema was still the dominant medium for film, with television being secondary and with even VHS tapes (let alone DVDs, streaming or NetFlix) being a long way off yet; this meant, for one thing, that films could afford to be more ‘complete’ and less narrowed for pop consumption and low attention-spans.

Doctor Zhivago, which also made a lifetime star out of a young (and extraordinarily beautiful) Julie Christie, is probably regarded as Sharif’s defining performance, comparable to how Lawrence is regarded in relation to O’Toole.

Sharif’s performance in Doctor Zhivago, noted for his refrained, almost passive nature throughout the drama, is something special. If Doctor Zhivago were remade today, one imagines it wouldn’t be anything like as enduring.

But in truth, neither Doctor Zhivago nor Lawrence ever need to be remade; both films have that rare, timeless quality that means they never really age or look overly dated. Which is a testament to, among other things, David Lean’s film-making.

And when it comes to a love story wrapped up in a historical epic, I would take Doctor Zhivago over Gone With the Wind any day.

Lawrence of Arabia, however, remains my personal favorite. A film that I usually watch once a year, it is in every sense an absolute masterpiece; cinematography, the scope of David Lean’s vision, the performances, everything. Omar Sharif’s own performance in that film is, even by his own later admission, one of the least immediately outstanding; certainly compared to O’Toole’s Lawrence, or to Anthony Quinn’s truly marvellous Auda Abu Tayi or Alec Guinness’s measured, eloquent portrayal of Prince Faisal Ali Hussein (the key figure of the Arab Revolt and would-be Hashemite King of Syria and later Iraq).

Yet by the third or fourth time you’re watching this film, you start to realise how crucial Sharif’s role is and how endearing his performance is. The scene below (the “nothing is written” scene) gets me in the gut every single time.

Unsurprisingly, Lawrence of Arabia has a whole lot of interesting anecdotal trivia around it, some of the most interesting involving Sharif.

One of the best of these, aside from the story of O’Toole refusing to acknowledge Sharif’s far-too-exotic name, is the story, as told by Sharif himself, of how Alec Guinness summoned the young Egyptian actor to his tent soon after arriving on location. To the young Sharif’s bemusement, the veteran British actor served him tea and then began questioning him about his life. This went on for some time, and the young Sharif noticed that Guinness wasn’t doing much talking himself, simply asking questions and then studying the younger actor closely as he gave answers.

Sharif was then dismissed, left confused as to what the purpose of the meeting was. It was only later that he found out Sir Alec had called him in to carefully study his Egyptian accent and mannerisms so that he could incorporate them into his own performance as the Arab Prince Faisal.

Alec Guinness’s charismatic portrayal of Faisal is in fact one of the very best things about Lawrence of Arabia; you tend to wonder if Sharif was watching him, thinking ‘he’s doing me better than I am’! But you do realise, once you’ve watched Lawrence enough times, that Sharif is crucial to the dynamics that work so well in the film. Guinness’s Faisal it all eloquence and politician, while Anthony Quinn’s magnificent Auda is the proud, almost Klingon-like warrior; but Sharif’s character is the more personable, idealistic, even naive, face of the Arab Revolt – a character who undergoes a discernible evolution through the course of the film.

Sharif Ali begins as Lawrence’s antagonist and judge, but ends up as his conscience and the innocent mirror to his actions. We don’t truly see how far Lawrence has gone, how much he has betrayed his own ideals, until we see it in Ali’s sense of disillusion and disappointment. Omar Sharif plays each of those stages perfectly; starting with the bravado and antagonism, evolving into guarded respect, then to true awe, even hero-worship, then to disappointment and uncertainty, and eventually to a form of true, pure friendship.

This evolution occurs all in just one film, and the fact that Sharif captures all of that vividly is rather extraordinary.

I wrote when Leonard Nimoy died earlier this year that with some actors, they become so much a part of our mindscape because they embodied characters that had become part of our shared mythologies. For me at least, Omar Sharif, like Peter O’Toole, was one of those; even though in fact he embodied something more like a myth within a myth, as Lawrence of Arabia was a cinematic mythologizing of a real-world historical period and event, which itself had already by then become an inseparable blur of myth and fact.

He is also the actor who has by far the most screen-time with O’Toole in the movie, and their inter-personal chemistry serves the film beautifully.

Sharif of course also had the most memorable introduction scene in the film; that famous long shot of Sharif Ali approaching from the distance on his camel, at first appearing to be a desert mirage, an almost ghostly figure floating on the horizon. It is classic David Lean film-making – unorthodox, visionary, and most of all patient; who else would have an approach-shot go on for that long and entirely in silence? But it’s genius; we, like O’Toole, are watching for what feels like a small eternity, waiting for this mysterious figure to take proper form and arrive.

Omar later revealed in interviews that this excruciatingly long scene for him actually needed multiple takes, because his camel kept making noises just as he was approaching his open dialogue – and every time it happened, he had to go all the way back to his start-point and do it again. What’s also remarkable about this scene is that it wasn’t merely Omar’s introduction into the movie, but his introduction into cinema itself (or at least into Western cinema); the first thing Western cinema-goers ever saw of Omar Sharif was this long, fascinating approach shot.

That being so, I’m not sure any actor in cinema history could necessarily lay claim to a more potent or memorable introductory moment.

Sharif and O’Toole meanwhile were lifelong friends, from the moment they met on location in Morocco to the day of O’Toole’s passing.

Like O’Toole himself, Sharif, despite appearing in some classic, enduring roles in his early film career, spent much of the rest of his life in the shadow of those early performances and subsequently appearing in a string of silly movies or projects that were probably beneath him (a made-for-TV movie with Angela Lansbury called ‘Mrs ‘Arris Goes to Paris’ is just about the worst of them, though the 1968 hit movie Funny Girl, co-starring the supremely untalented Barbara Streissand, though popular, is another I find virtually unwatchable).

However, he also appeared in some more genuinely memorable roles. One of these was the largely-forgotten, though actually very good, historical epic The Fall of the Roman Empire, which also features Alec Guinness as Marcus Aurelius, Christopher Plummer as a mesmerising Commodus (long before Joaquin Phoenix portrayed the same character in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator), as well as Stephen Boyd, James Mason and Sophia Loren. Anyone who’s never seen that film, by the way, should seek it out; it has a really fantastic opening 45 minutes or so, though it does kind of fizzle out.

Sharif’s comic appearances in Blake Edwards’s Pink Panther movies are also something I love watching, just for the sheer out-of-character randomness of it.

Among some of his other better-known movies, Sharif had the pleasure of starring with Ava Gardner (along with Catherine Deneuve and James Mason) in the film Mayerling (this time Sharif is Austrian royalty). I have a curious relationship with films of this kind, which in many cases aren’t any kind of cinematic masterpieces, but nevertheless lure me in out of sheer desire to watch people like Sharif and Ava Gardner on-screen together.

The aforementioned film he made with Barbara Streissand (1968’s Funny Girl) was angrily boycotted by almost all Arab states and caused particular outrage in his native Egypt, due to his on-screen romance with the highly pro-Israel Streissand. This was, to make matters worse, during the days of the Six-Day War between Israel and the Arab states.

For all the many places his career took him, everywhere he lived or worked, Sharif remained closely tied to his Arab roots; he was born in Egypt and he died in Egypt.

His exotic foreign persona (combined perhaps with his mastery of several languages) had made him a go-to-guy for foreign characters in American movies. Sharif joked that after Anthony Quinn had died, he now had the market in Hollywood Arabs all to himself. He wasn’t just type-cast as ‘the Arab’, however, but played everything from German, Austrian, Spannish, Latin-American, even the legendary guerrilla fighter Che Guevara (not to mention the Mongol, Genghis Khan).

Sometimes this resulted in almost comically mismatched performances; when he played a Wehrmacht General, for example, in the film Night of the Generals, he did the whole thing in his Egyptian accent (!). His friend Peter O’Toole was in that film too and he too played the entire thing basically as Peter O’Toole; there wasn’t a German accent in sight. I guess the method approach wasn’t really in fashion yet. It’s a pretty poor film, but I couldn’t help buying the DVD anyway, purely for watching O’Toole and Sharif ditching the Arab robes and donning Nazi uniforms.

The frustrating thing about the careers of people like Sharif, O’Toole, and for that matter Richard Burton, is that their filmographies are a highly up-and-down ride of utterly classic roles mixed with entirely forgotten or forgettable films and downright embarrassing ones.

This was in part due to the fact that their careers spanned a very changing, evolving period in cinema and film-making. Actors like them, in terms of their film careers, came to prominence during an era of particularly epic film-making in the early sixties (Lawrence, Zhivago, Cleopatra, etc) but were then left struggling to sustain their careers as film-making fashion shifted abruptly even in just the sixties, let-alone the seventies and beyond.

And Sharif, unlike say O’Toole or Burton, wasn’t a stage-actor and couldn’t return to the theater. So he was, after a certain amount of time, somewhat adrift as far as his film-career was concerned. That wouldn’t really happen today in mainstream cinema; I tend to think that actors, even as they age, continue to be offered good work and are, for that matter, more discerning about which roles they accept these days too.

Sharif, for his own part, downplayed his own acting abilities or caliber and regarded himself more a ‘film star’ than an O’Toole type Actor. He would’ve presumably remained an Egyptian film star for some time, but he really did owe his international film career to David Lean and to Lawrence.

Outside of film, Sharif was rather well known for his gambling habits and his obsession with casinos, where for many years he had spent a lot of his time, racking up substantial gambling debts along the way. But he was in fact less the classic ‘gambler/obsessive’ and more genuinely fascinated by the games themselves. Possessing a highly mathematical mind and faculty, one of the most interesting facts about him is that Sharif was once ranked among the world’s top 50 contract bridge players (and even once took part in a match in front of the Shah of Iran). He also once explained that it wasn’t the winning of money that drew him to the casinos, but a mixture of the ‘glamour’ and also the fact that it was one of the few places where, as a famous film star, he could go alone and not look like a loner (such as eating alone at a restaurant).

I remember seeing an interview the elderly Sharif did on Johnathon Ross’s BBC talk show a few years ago. What struck me was that it was one of the funniest and most entertaining interviews I’d ever seen on that (or any other UK) talk show. A large percentage of the audience probably didn’t know who Omar Sharif was, but he had a class of charisma and honesty that was so palpably different from what we’re used to seeing in contemporary ‘celebrities’ and ‘interviews’.

While Sharif had never necessarily been ‘chat-show gold’ on the kind of level that people like Orson Welles and Peter Ustinov were, he nevertheless still had some degree of that old-school charm and fascination. There’s something about some of those old-school performers that made them far more engaging interview subjects than what we get with most contemporary stars. This might be partly because the entire style of interviewing has shifted since then.

It might also be because the culture has also shifted and the modern ‘celebrity culture’ and the accompanying interview ‘circuit’ conveyor belt has gone into overdrive. It might also, however, be as simple as older people having much more interesting things to say, having had longer, more eventful lives. Or maybe there was something different in the water back then.

Not really that interested in plugging any latest product or project (which is what most interviewees on talk shows are there to do), Sharif began the interview by worrying he was “going to be an anti-climaxe” after the various younger, more ‘now’ guests. That said, Johnathon Ross was deferential enough to make Sharif the ‘headline’ guest on that show, despite the fact that he would’ve been largely unknown to much of the audience.

That was the last time I saw Sharif on TV, but it was a memorable interview (I’ve looked for it on You Tube, but sadly can’t find an upload; I did find this quite interesting Omar Sharif interview, however). Aside from talking about his career, he also talked openly about his gambling days and even his awkward history with women. Omar Sharif, remarkably for a Hollywood film star (especially one generally considered so handsome), only ever married once, and he had, for that matter, married his wife (the Egyptian actress Faten Hamama, with whom he’d co-starred in the film Struggle in the Valley) prior to being taken to Hollywood or becoming an international star.

But he had divorced her in 1974, claiming it was because he didn’t want to betray or dishonour her by “falling in love with some stupid Hollywood starlet”. The price was that he claimed to have never fallen in love again, and he regarded this as some kind of “divine punishment”.

Despite obviously being around scores of highly glamorous women in his career, including co-stars like Ava Gardner, Sophia Loren, Julie Christie, Audrey Hepburn and others, Omar appeared to have not been in any serious relationship after 1966. He joked to Johnathon Ross that he preferred “ugly women” to beautiful women anyway, adding that he liked a woman “to have gratitude”. It wasn’t entirely clear whether the 70-something year-old was joking or being serious; but either way, it was hilarious.

It is curious to note also that his only wife, Faten Hamama, also died this year, less than six months before Sharif.

With due respect for all the various elements of his life and career, for me the main thing I’ll always remember Omar Sharif for is Sharif Ali in Lawrence of Arabia, which is hardly surprising as this remains one of my favorite (maybe my absolute favorite) film and it is a role characterised by so many memorable scenes or moments.

And just as Sharif got that unforgettable opening moment in the movie, he (and Anthony Quinn too) also got a really special exit scene too; and when I heard Omar Sharif had died, the very first image that came to my mind was that very scene of him walking across the moonlit Damascus courtyard and disappearing into the darkness.

It’s a highly romantic moment, but then the two main movies Sharif is most associated with are so full of romantic heroism and imagery and David Lean’s characteristic cinematic Impressionism, that these are naturally the immortal images and memories that will linger long after Omar Sharif’s mortal lifetime.

Played bridge against him back in the 70s. He was indeed a top player.

Thanks John, I’m glad to know he wasn’t just bragging. I’m also delighted to exchange words with someone who played bridge with Omar Sharif.

Enjoyed your thoughts and anecdotes in this homage to Omar Sharif!

Thanks 🙂 I loved the guy, so it was easy.