Recently, during a standard, heated argument about the Star Wars prequels, someone challenged me to “name ten things” that were good about The Phantom Menace.

I’ve been having this argument with people for years and have therefore already expended plenty of brain-power thinking about this in the years since 1999. As a new chapter now begins in the Star Wars saga, I thought now was a good time to cast our minds back to 1999 and the last great beginning of the last great chapter.

We could talk about all the things that are wrong with Episode I – and that’s precisely what far too many whinging people have been doing for fifteen years. There are problems with Episode I, without doubt; a number of questionable decisions, misfires and iffy moments.

But there was plenty right about the film too and a number of genuinely, really good things in the movie.

If you had never seen The Phantom Menace but had simply been exposed to the tiresome plethora of hatred for the film and the accompanying hatred of George Lucas, you might be forgiven for thinking Star Wars: Episode I is the worst film ever made. You’d be forgiven for thinking there was nothing good in this film and that it wasn’t worth even watching.

You would be extraordinarily wrong, however.

Though a very long way from perfect and though deeply flawed in specific areas, The Phantom Menace boasts some of the very best things Star Wars has ever offered; and one or two of the best things cinema itself has ever offered.

Here are 10 things that were genuinely great about The Phantom Menace; and I’m not even going to include the incredible trailer, those tone poems or that wonderful Anakin/shadow poster (which, by the way, still hangs unashamedly on my wall)…

Exquisite Design and Craft, Beautiful, Breathtaking Worlds and Settings

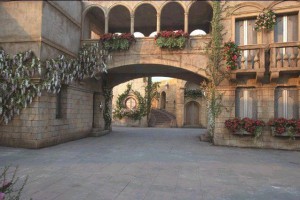

This is something a lot of people tend to overlook. But the settings in The Phantom Menace are wonderful and are one of the first things I think of when I think of this movie. Conceptually, it’s all stunning, from the Roman-esque or Renaissance majesty of Naboo to the stunning underwater city of Otoh Gunga to the evocative, compelling Metropolis of Coruscant. In terms of exotic or interesting worlds and backdrops, The Phantom Menace does better than any other Star Wars movie.

In fact, it does better than almost any sci-fi movie I can think of. And from concept art to on-screen realisation, it’s just epic.

Clearly this kind of magnificent backdrop is something Lucas really dreamt of doing for a long time and was unable to truly accomplish within the technical constraints of the Original Trilogy. However, this difference between the prequel trilogy and the Original Trilogy also makes perfect sense within the logic of the Star Wars narrative and therefore sits comfortably within the broader mythology. As Lucas himself explains, the world we knew from the Original Trilogy – that dusty, beat-up, second-hand world – was a universe removed in time from the ‘golden age’ of the galaxy.

This was a post-Republic era, a darker, grimier time in the galaxy, where things don’t work so well, things are more broken down.

But the galaxy we were introduced to in Episode I was in essence the only time in Star Wars we glimpse what the galaxy was like in its (relatively) enlightened era, where the Republic is still fully functioning and there is democracy and peace. By Episode II, things are starting to change already but here in Episode I we’re still seeing that Augustan Age and it is beautifully reflected in the visual feel of the settings.

But the fact that Naboo and Tatooine are so opposite in scale and character is a testament to the diversity of the galaxy George Lucas always envisioned; a galaxy filled with diverse and vastly different worlds and societies. The Tatooine we revisit in Episode I is thoroughly engaging, for that matter. It’s a much more expanded and explored Tatooine than we saw in the Original Trilogy. While the podrace gives us those epic, expansive backdrops, canyons and other megalithic features, Mos Espa gives us a vibrant, bustling little desert trading port, filled with character. The Mos Espa scenes have a wonderfully Middle-Eastern flavour, while the slave quarters and homestead evoke the kind of historic settings and mythologies of those old epics like Ben Hur and The Robe.

Meanwhile the costume design and the general, broader quality of concept designs and the visual look of most of the film is exquisite.

This was really craftsmanship of the highest level to create visually stunning elements all over the place; from some of Amidala’s costumes to the Coruscant interiors, the breathtaking aesthetics of Naboo and Theed, the gorgeous design of the podracers, the sleek, elegant design of the Naboo Starfighters, the nerd-gasm of the Battle Droids in general and the Destroyer Droids in particular, and much more.

Darth Maul

Darth Maul is one of the coolest, most bad-ass characters in the Star Wars saga. He is also the Boba Fett of the Prequel Trilogy; that same kind of silent, mysterious, bad-ass figure as Fett was in Empire Strikes Back. The fact that Maul is kept so mysterious and quiet is part of why he’s such a great presence.

We know so little about him or his thoughts, but the silence only serves to amplify the palpable sense of anger and Dark Side malice emanating from his every expression, his every sneer and his every ultra-aggressive move. The ill-will and negative energy is so palpable in Maul in such a visual way that dialogue would actually only ruin it. Lucas was spot-on with this character in every respect.

Maul is the mystery figure (the ‘phantom menace’) who is the visible manifestation of the crisis facing the Jedi and the galaxy – the visible threat representative of the greater, though as-yet-unseen threat of Darth Sidious. And for a figure who represents this intrigue and mystery, Lucas made him suitably and visually intriguing and mysterious to reflect this. You sense that Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan have a dozen questions they want to ask him to figure out where he’s come from and what’s going on; but Maul remains the silent figure, who’s mission is to fight and kill and to reveal nothing.

The entire idea of this bad-ass Sith Apprentice hunting down the Jedi on Tatooine is a great plot device in itself, even if we only see a little of it (even that night-time shot of him arriving on Tatooine in his Sith Interceptor is terrific). The initial clash between Maul and Qui-Gon on Tatooine is brilliant; it gives us a taste of what’s to come later, but is otherwise a quick, fleeting scene, the two of them like ships passing in the night before Qui-Gon flees and Maul is left dissatisfied. It’s a great moment, brilliantly paced (the Anakin drop is a great detail), knowingly refrained, but entirely exciting.

This is, remember, the first encounter between a Jedi and a Sith in thousands of years; so while Maul, who has been waiting for this for ages, is visibly relishing the fight, Qui-Gon, who is caught entirely off-guard and mystified, is on the defensive and wants to get away safely with Anakin and resolve the mystery later.

In all, Darth Maul was a brilliant presence in the mix. And that big reveal later on, with the doors sliding open to show him standing there, is one of the best entrance scenes in all cinema.

The Duel of the Fates Lightsaber Battle

The climatic confrontation between Darth Maul and the Jedi is of course the centrepiece of the entire movie and is, I maintain, one of the greatest moments in all Star Wars. It is superb on multiple levels, some obvious and some more subtle. The choreography is just magnificent, the sequence is visually stunning, and the whole thing is bathed in the glory of John Williams’ epic ‘Duel of the Fates’ score.

One of the things we have to remember is that we had never seen lightsaber fighting like this before; from the Original Trilogy, we were used to comparatively slow, stilted duels. That of course makes sense; by the time of the OT era, lightsaber duelling was a thing of the past as the Jedi were extinct, therefore it makes sense that the elderly Kenobi and elderly Vader in A New Hope would be laboured and rusty, and it also makes sense that Luke would be equally as slow and halting in his duels with Vader, as he has had minimal training and he doesn’t live in a galaxy where lightsabers are common.

But of course in the Episode I era, we are right in the midst of the Old Republic and the Jedi Order and therefore the lightsaber fights we see are much more fluid and skilful. It blew us away in 1999, and it still blows me away even now. This sequence is just cinematic brilliance; and if it wasn’t for the fact it keeps getting disrupted by cut-aways to Gungan antics, it would be even better.

From the moment the (phantom) menacing Darth Maul makes that brilliant entrance, revealed as the doors slide open, the entire sequence flows beautifully, like a stunning synthesis of opera and performance art.

There are terrific little details too; Maul using the detached droid-head to open the doors, for example, or the fact that we can really feel the anxiety and impatience of Obi-Wan when he is separated from the fight and is forced to watch his Master from behind a forcefield.

That sequence with the forcefields is itself a brilliant touch, as it plays with momentum and increases tension – before this, we’d been watching a fast-flowing, highly kinetic fight sequence, but then it suddenly just comes to an abrupt halt.

Obi-Wan falling away and having to leap and run and try to keep up with the Qui-Gon/Maul fight is also cool, depicting Obi-Wan’s inexperience and Padawan-ness. There is naivety in Obi-Wan’s fighting; though visibly more skilled than Qui-Gon, Obi-Wan is more over-eager and lacking in caution, which is why he’s briefly knocked out of the fight and is the reason he ends up separated from his Master (and the reason, therefore, why Qui-Gon dies).

This is later subtly touched upon in both Episode II and III, when the older Obi-Wan cautions his own apprentice about fighting Count Dooku “together” and not rushing in separately. Obi-Wan’s naivety at this stage is also shown in his solo duel with Maul once Qui-Gon is incapacitated; although he comes rushing out with brilliant speed and flowing swordsmanship, his lack of discipline lets him down and a wild, unfocused swing at his opponent allows Maul to outwit him, and before he knows it Obi-Wan is hanging on for dear life, watching his lightsaber topple into the abyss.

This is terrific, albeit subtle, little detail. What we see here is a young, reckless Obi-Wan who comes at Maul with too much aggression and emotion, while Maul, by comparison, is all calm, eloquent and at one with the Dark Side of the Force. In Episode III, an older, wiser Obi-Wan is now the one fully in-tuned with the Force and it is Anakin who is emotional, undisciplined and pretty much self-defeated, the way Obi-Wan is in Episode I.

There are two things in particular I think are superb creative decisions on Lucas’s part in this sequence. The first, as I noted above, was having Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon be separated by the forcefields. It just added so much more tension to the sequence. We may take it for granted now, but think about it: it wasn’t necessarily an obvious choice. Lucas could’ve just as easily had Qui-Gon killed during a continuation of the three-way duel. But by separating Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan, the sequence becomes so much more dramatic. Every time I watch it, I can *feel* Obi-Wan’s tension and helplessness as he watches, unable to join in; I mean I literally feel twitchy and restless, almost wanting to get up and join in myself.

The second genius thing is when Qui-Gon is eliminated and we get down to that brief Obi-Wan/Maul solo duel – which is so good, by the way. Aside from the stunning speed and fluid choreography, it is also aided by the complete silence; this was a genius dynamic, because the whole sequence until then was awash in the compelling choral tones of the ‘Duel of the Fates’. But after Qui-Gon is out of it and we come back to an angry, over-eager Obi-Wan waiting to get revenge, there is no music: instead Kenobi and Maul fight in silence, the hums and clashes of the lightsabers themselves becoming a sort of naturalistic music.

For all the legions of Lucas-haters who, rather astonishingly, refuse to give him any credit for anything, this sequence and its dynamic elements is a shining example of how brilliant Lucas’s conceptions can be.

Qui-Gon’s death itself is a compelling moment for the abrupt way it happens, with a sudden upper-cut to the chin disorienting him and then an immediate once-through with Maul’s weapon. This whole sequence sort of made me think of something like Enter the Dragon; interestingly enough, the fight choreographer, Nick Gillard, did say that Lucas had asked him to basically “invent a martial art” for the Jedi/Sith dynamic and for this sequence in particular. And that’s pretty much what we get; something that feels like a cross between swordsmanship and martial art. This was particularly achieved through Darth Maul and the winning decision to cast a martial-artist, Ray Park, in the role in order to truly achieve that superb level of physical ability on-screen.

Finally, having Obi-Wan reach into the Force in order to leap up and cut Maul in half is a terrific moment, in keeping with the OT vibe of what the Force is really about: his leap is literally a leap of faith in the face of despair and imminent death. The fight is lost, Qui-Gon is dying and Obi-Wan is experiencing a moment of utter hopelessness; but to the last breath, he doesn’t give up hope in himself, he believes in the Force and he takes this leap of faith in order to finally overcome his superior opponent.

It is a moment, a conclusion, totally in keeping with all those classic, nostalgic Yoda teachings to Luke in the Dagobah swamps of Empire Strikes Back; a moment that really exemplifies what the Force and the Jedi are about, more so than any other moment in the Prequel Trilogy.

For anyone who mocks The Phantom Menace or dismisses it out of hand, I invite you to re-watch this entire sequence.

The Podrace

I don’t comprehend how anyone can dismiss The Phantom Menace when it has this sequence in it. On a technical level, the Boonta Eve Podrace might even be the greatest overall action sequence in Star Wars.

It’s just brilliant. It’s immaculately conceived and realised, it’s tongue-in-cheek, it’s visually incredible, it’s rich in detail and layer, even the sound design is utterly superb. The amount of meticulous work that went into creating this sequence – which on its own took two years to complete – is mind-blowing. The artists and designers who brought this thing to life, from the conceptual stages to the end product, did an extraordinary job. Setting out those amazing backdrops and gargantuan canyons, ravines and landscapes in the desert was an immaculately executed job in itself, even without the actual race.

The race itself is fabulous, partly inspired by the chariot race in Ben Hur (right down to Sebulba trying to do the dirty tricks like Messalla) and part Wacky Races, but underline by Lucas’s love of motor racing and fast cars. It’s just an immense sequence that is pulled off perfectly and that no other filmmakers would’ve even dreamt of attempting. The scale of it, the ambition and vision, is to be marvelled at, from the vast backdrops, the Roman style arena and the panache and bombast of the race, right down to the great designs of the pods themselves and all the little add-ons like the intriguing shot of Aurra Sing, the wandering Jawas, the Tuskens sniping at the racers, and the fact that we see a younger Bib Fortuna with a younger Jabba the Hutt who watches the whole thing like a bemused, bored Pharaoh (and even falls asleep).

There are some annoying things in this sequence – Jar Jar, the cutaways to the kids, the annoying-as-hell commentator; and much of the stuff revolving *around* the race is really bad, such as some of the Shmi dialogue (the “you have brought hope to those who have none” line is just awful). But overall the podrace is one of the most spectacular and brilliant sequences there’s ever been in *any* film, let alone just in Star Wars. And this was 1999, by the way.

One of the things I loved about the podrace sequence is that it really evokes that larger-than-life, old-style historic epic, partly made obvious by the Ben Hur homage. Aided by the desert settings of Tatooine, it makes the Anakin Skywalker origin story evoke the kind of thing you’d find written in long-lost scrolls, telling great stories of long-gone epochs and great heroes and grand races. The film as a whole actually more broadly has that effect too, which was something I always loved.

I challenge anyone to find me any sequence in any film ever made and put it up against this podrace sequence for technical, visual or editing brilliance. The fact that a technical or special-effects Oscar wasn’t forthcoming for this sequence alone is demonstrative of the extent to which Hollywood resented and disliked George Lucas.

Naboo

From that very first shot of the Royal Palace and the waterfall, Naboo, and Theed in particular, are utter breathtaking. The concept art for Theed is pretty evocative on its own, but what we end up with on-screen, in all its rich detail and Renaissance splendour, is truly special.

Both at the macro level, with the wide shots and epic backdrops, and at the micro level with the specific details, every element of Theed is masterfully rendered. Although Caserta in Italy was used as a kind of base layer, most of this is a computer-generated city that doesn’t exist in the real world; but it’s utterly compelling and looks more real than anything in Episode II. Every shot we see of Theed, every interior and every exterior, is so rich with fine detail and nuance, bringing to life a grand and idyllic city and society.

There are elements and details that, if anything, aren’t exhibited enough, where you have scenes that move too quickly and you only get a fleeting glimpse of the background; for example, the scene where the Battle Droids are leading the Amidala decoy and her entourage down the palace steps, there is this wonderful background of the enormous statues on giant plinths flanking the wide stairway – it’s the kind of visual you want to linger on a little more, conveying that there’s so much more to see in the setting. This demonstrates the depth of the work that went into making this city and planet genuinely complex and visually/architecturally engaging.

Theed really is the conceptual centrepiece of Episode I and may be the most magnificent world/setting we’ve ever had in Star Wars, even if the more familiar settings of Tatooine – really the exact opposite of everything Theed is – are where we have the most nostalgia.

Meanwhile, Otoh Gunga, the underwater Gungan city, is just as breathtaking as Theed. Of course it’s ruined somewhat by how annoying Jar Jar and the Gungans are, but conceptually and visually, this is a stunning sequence. That first sight of Otoh Gunga, as the fish clear away to reveal these luminous, transparent bubbles arranged in their complex, bewitching configuration, is truly gorgeous.

Whoever came up with this whole concept of the organic-feeling underwater village was a genius. And as annoying as the Gungans themselves are, this idea Lucas pursues here of the two vastly different societies inhabiting the same planet – one on the surface and one below the water – is a genuinely interesting one; probably more so on paper than on the screen.

In the end product, the exploration of this ‘symbiont circle’ theme in the film falls flat because the Gungans are so difficult to watch or take seriously; but I can totally see and appreciate what George was conceiving of on paper.

The “Boring” Politics and the Republic

One of the things that bothers me most about the common, whiney criticisms of The Phantom Menace is the constant complaining about all the ‘boring politics’ and the ‘boring Senate’, etc. This is a complaint, essentially, of pop-corn munching, action-movie enthusiasts who have the attention-span of fish and can’t stomach twenty minutes without an explosion or speed-chase.

The ‘boring politics’ are in fact one of the most interesting things about Episode I and were, moreover, always going to be necessary, because the prequels were always going to be just as much about the fall of the Republic than about the corruption of Anakin Skywalker.

The politics we get in Episode I are genuinely interesting, much more considered than anything we’d had in The Original Trilogy. We see a Republic that has grown fat and tired, crippled by a massive, ineffective bureaucracy and bogged down in regulations, corporate interests and influences, and with, as Palpatine puts it, “no interest in the common good”. That’s a very interesting dynamic to encounter, because I always assumed that some big dramatic coup or crisis is what ended the Old Republic; but what George shows us in Episode I is much more mundane, much more layered. The Republic has simply become a complex corporataucracy filled with lazy politicians and representatives bogged down in rules and regulations and “mired in corruption”.

There are no ideals or passions, just day-to-day business. It’s this condition on Coruscant and in the Senate that allows Palpatine/Sidious to step in and begin his master-plan to take over the galaxy. And Episode I gives us that start-point for the process that will eventually end the Republic and also make Palpatine the Emperor we knew and loved/hated from Return of the Jedi.

It astonishes me that people have complained so much about this part of the story, given that it’s only basically two or three scenes and it establishes so much. Also, in terms of it being ‘boring’ or slow-paced, I think George was trying to depict the mundanity from which tyranny or vast corruption can occur; just a hum-drum day in the Senate, involving a minor crisis and a minor planet, actually turns out to be the mechanism by which essentially an Anti-Christ type figure is able to manipulate everyone into installing him into what will soon become a dictatorship.

I have to confess here also that I’m of the school that is able to see the Star Wars story as very much a parable about real-world geo-politics and false-flag terrorism/war. I also think that George – whether he admits it or not – deliberately intended it to be. In the earliest drafts for Star Wars in the 1970s, George even wrote on one of his documents that “the Empire is America ten years from now”.

That being so, it’s always interesting to me to watch the false-flag war of Episodes II and III, where Palpatine is controlling both sides of the war in order to advance his plan, and then to watch real-world geo-politics and proxy wars in, for example, Syria and Iraq. In that context, the ‘boring politics’ of Episode I are especially interesting, because it’s clear George was writing a story about both a corrupt, lazy bureaucracy, and about the rampant corrupting influence of corporate leviathans on democracy and government. That was clearly why the main villain faction in Episode I was called ‘the Trade Federation’ and then in Episode II we also get a whole bunch of factions with names like ‘The Corporate Alliance’ and the ‘Banking Guild’ or whatever.

Without doubt, George was trying to write a galactic story about corporations corrupting government and undermining the common interest.

It’s in Episode I that this parable is most pronounced, as we have the ‘Trade Federation’ illegally ‘taxing trade routes’, leading to an invasion of Naboo. Now, yes, all the talk of ‘taxation of trade routes’ is, on the surface, pretty dull language – but that’s the whole point. It’s this dull, bureaucratic speak and equally dull, bureaucratic response of the Senate, that perfectly illustrates the ineffectiveness of the vast government institutions at this point. It’s this dull, procedural business – with everyone bogged down in legal-speak, equivocation and the letter of the law instead of morality or humanitarianism – that results in a planet being invaded, in a well-meaning Chancellor being ousted and in a Sith Lord being appointed to control of the Senate.

That’s the point of this part of the story; Amidala comes to Coruscant pleading for help against illegal domination by a vast corporation, but she instead finds a hesitant Senate quoting procedures and regulations to her.

Those scenes – and the actions of the Trade Federation – are *meant* to be a little boring, because it’s showing the mundanity that the tyranny came from.

And the fact that Palpatine is precisely relying on this quagmire of the Senate and the “greedy, squabbling politicians” in order to carry out his scheme shows just how predictably ineffective the political system and the Senate has become.

Palpatine’s Manuevers

The story of how Palpatine, a seemingly minor representative in the Senate, schemes his way to power is genuinely interesting to watch. It’s entertaining to watch him maintaining this nice guy act, this concerned, well-meaning politician act, throughout the film, and then watching his Darth Sideous alter-ego operating from the shadows. Sideous is of course the ‘phantom menace’ of this film, and this Jekyl and Hyde routine throughout the film is one of the best storytelling ideas Lucas went with for Episode I.

The sight of the future Emperor appearing in menacing holographic form to his collaborators and issuing orders, while also doing the Mr Nice Guy Palpatine act elsewhere is a really good dynamic. Those scenes are ruined somewhat by the silliness of those Neimodian Trade Federation characters and their silly accents, but the dark, occult influence of Darth Sidious in the shadows is still put across.

After Return of the Jedi I had always wondered what the Emperor had been like in the past and how it was he had come to power, and Episode I begins to answer the question.

It’s great to watch Palpatine at this stage, being such a manipulator and schemer, while still having to put on the facade of the caring politician. The Palpatine we were used to was the Emperor of Return of the Jedi, where he didn’t have to do anything but sit on his throne and sneer, the whole galaxy under his dominion. But here, we meet a Palpatine who still has lots of work to do and is working his way towards his diabolical goals. And it adds effectively to the overall mythology; Episode III would do it much better and put the final touches to the story, but Episode I sets the path up nicely. Watching Palpatine manipulate Amidala so completely is cringeworthy for all the right reasons, particularly when he’s whispering in her ear during the Senate session.

That lingering shot of Senator Palpatine’s expression after Amidala leaves and tells him “I pray you can bring sanity and compassion back to the Senate” is priceless, rich with foreboding and dramatic irony. In the same vein, I always loved the way the moody, atmospheric scene of Qui-Gon’s funeral has the camera pan across everyone’s face before finally settling on Palpatine’s just after Mace Windu asks Yoda “which was destroyed – the Master or the Apprentice?”

In general anyway, this first look at Palpatine – the secret Sith Lord – skilfully navigating his way to power via the corruption and inadequacy of an ineffective political system is really good material. His scheme is executed expertly, all geared towards having Chancellor Valorum ousted from his position, and the Dark Lord of the Sith, firmly entrenched in the politics and bureaucracy of the Senate and government, is able to manipulate everyone easily, all while the great minds of the Jedi Council have absolutely no idea that the Sith Lord is right in front of their eyes.

The prequels, as much they are a story about the Sith Lord’s expert manipulations and foresight, are also a story about how inadequate the Jedi are – but that’s another matter.

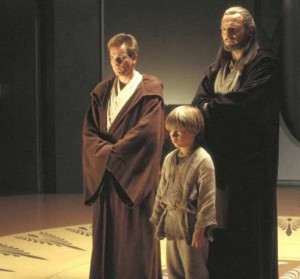

Qui-Gon Jinn

Some may argue that the character of Qui-Gon Jinn was ultimately unnecessary in the broader trilogy and that his role in Episode I could’ve simply been carried out by Obi-Wan Kenobi on his own. However, what you’re missing if you think that is that George Lucas obviously wanted to show what Jedi life was like in the Republic era (“before the dark times”, as Alec Guinness would later put it) – and a key part of that was showing the Master/Apprentice dynamic in action.

Further, Episode I was set in a time-frame that meant Kenobi would be too young to be a Jedi Master himself; therefore it was logical to have him as an apprentice.

And further, had we not had the character of Qui-Gon Jinn, we would’ve missed watching Liam Neeson as a Jedi Master – which is one of the strengths of Episode I. Liam Neeson gives us the most perfect embodiment of what I always imagined a Jedi Master would be like; aside from Alec Guinness, I don’t think anyone actor has captured and embodied that Jedi Master dynamic as effectively Neeson does throughout this film. Calm, thoughtful and contemplative, tempered throughout, Qui-Gon Jinn is a character I’m glad we had, however ultimately short-lived or disposable he was.

It’s interesting that while Episode I has some noticeably awkward, stilted performances in some areas, Liam Neeson is the one who looks most comfortable, able to easily play his part with quiet conviction and subtle charm. Think of how much more awkward this movie would’ve been if every one else had given basically the same performance but Liam Neeson/Qui-Gon wasn’t in it at all. But Qui-Gon brings to Episode I essentially the same weight and gravitas that Alec Guinness brought to the first Star Wars.

Coruscant

And then there’s a first experience of Coruscant. Well, ok, not our first experience precisely – we did see a quick glimpse of Coruscant in the Return of the Jedi Special Edition. But even so, in 1999 this was one of the things I was most curious about seeing. In the old Star Wars novels (I only ever read the early ones, up until around 1995), we always heard about Coruscant and how it was the capital of the Empire, but that it used to be this great, magnificent capital of the Old Republic.

In Episode I, we finally saw it and it was suitably absorbing, a rich feast for the eyes, with its gargantuan skyscrapers and complexes and ever-streaming airlanes.

Futuristic, densely-packed cities have been shown in films before, of course; but Blade Runner was much grimier and more industrial than what we see in Episode I, while The Fifth Element was dirtier, messier and more overtly New York. The Coruscant of Episode I, on the other hand, was much more majestic and more clean. In Episode II we get more of a street-level view of the planet and in fact it loses some of its charm; here in Episode I, we’re seeing it from an aloof perspective, only from high vantages and with fascinating, evocative backdrops.

Pretty much all of the Coruscant scenes are visually gorgeous; the moody reddish hue to the scene where Anakin is facing the Jedi Council, for example, with the rich details of the vast backdrop intruding in via the broad window, or that magnificent sunset shot as Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon are walking on the gantry and looking out at the city. This is CGI at its very best.

In Episode I, there is still a strong element of real-world reality to the vast settings, even though most of it is computer-generated, whereas in Episode II the CGI completely takes over and the sense of reality starts to erode in places. The interiors are just as rich; the interior design to Amidala’s quarters on Coruscant are superb, really giving those scenes a strong aesthetic, while the ever present shots of the cityscape from the windows keep even the smaller moments visually engaging.

John Williams and the Soundtrack

I know John Williams pretty much goes without saying as a major strength of any Star Wars movie, but for The Phantom Menace I think he warrants specific citation. The Episode I soundtrack is just unbelievably good – I mean pretty much off-the-scale. While all the music in Star Wars is generally wonderful, if I had to pick the individual film with the best overall score I would be picking either Episode I or Episode III.

In terms of Episode I, even though the entire tracklisting is superb, there are the two central themes that are the most memorable and the most significant; the Duel of the Fates theme and the softer, slower ‘Anakin Theme’.

The fast-paced, choral magnificence of Duel of the Fates really was whole new ground for Star Wars in 1999, taking things up a level in musical terms. Aside from a brief – though brilliant – swell of music during Luke Skywalker’s final assault on Vader in Return of the Jedi, I don’t recall there ever having been choral element to Star Wars music before this. It really imparts something extra epic to the three-way duel at the end and it’s impossible now to think about that sequence without that music. It’s strategic re-use during the end duels in Revenge of the Sith weren’t quite so effective (the ‘Battle of the Heroes’ score that Williams wrote for the Anakin/Obi-Wan duel was actually even better, though it was conceived as an evolved version of this original ‘Duel of the Fates’).

The ‘Anakin Theme’ is also a real masterstroke, a real piece of John Williams brilliance, that captures the emotional core of the movie.

It has an obvious air of romanticism to it, but it’s essentially bittersweet and it has that clever, subtle hint of the Original Trilogy’s Vader/Imperial March theme. But that tonal, musical link is so subtle and refrained that it qualifies as genius.

It really is a beautiful piece of music, lucidly capturing an obviously intended sense of childhood and innocence, but yet with that subtle, underlying sense of foreboding for what the future holds.

The fact that Williams was able to express or capture all of that in a composition of classical music, right down to musically expressing the shadow of Vader in key notes, is testament to his genius.

____________________

And you know what, I could probably stretch it to more than ten (I haven’t even mentioned Watto the slave owner); there were other things I still like in this film too, not least the expansion of the mythology to more epic proportions.

But for those of you hate The Phantom Menace, I know nothing will change your view, so it probably isn’t worth trying too hard to evangelise for this movie.

Episode I ultimately remains, and always will be, an immensely frustrating thing. Brilliant and memorable in places, misjudged and problematic in others. Intriguing and clever in parts, while confused and jarring elsewhere.

The biggest underlying problem is that Lucas never seemed to settle on a tone. There is stupidity mingled with genuinely magnificent storytelling. Badly scripted, even badly acted, in places, it nevertheless boasts a handful of beautifully rendered scenes and at least two absolutely spectacular, brilliant sequences, all the while there is a stunningly high level of artistry involved in various aspects of the production and of a standard that leaves most big-budget cinema trailing miles behind.

The most frustrating thing for me as a lifelong Star Wars fan is that I can sense what Lucas might’ve been going for with most of this and I can tangibly *feel* and *see* how much better Episode I could’ve been had key misjudgements not been made. This is evident in just reading the novelisation, let alone just using your imagination.

Because the conceptual side of it is staggeringly good. And the story itself is very, very good too. What’s frustrating is knowing how good so much of this film genuinely is and then also seeing how much so many people hate it; the worst part is that I can obviously understand why people hate it, because there are some obviously valid reasons.

But ultimately I feel that those people are missing out on what special pleasures this film still has to offer. And the cliché of simply branding this film as “bad” simply reveals a lack of insight; it has never been as straightforward as that.

More: ‘Is REVENGE OF THE SITH the Greatest Work of Art in Our Lifetimes?‘, ‘Every STAR WARS Film Revisited/Re-Analysed‘, ‘Why RETURN OF THE JEDI is the ONLY Fitting End-Point for the Star Wars Saga’…

It’s obvious you disagree, but in addition to everything you said that helps make Phantom not only my favorite Star Wars film but my favorite film period is in fact – Jar Jar. I think a lot of people missing key points with Jar Jar. Yes he is “annoying”, but he’s clearly supposed to be as evidenced by the fact that he has this effect on most of the characters in-universe. Obi-Wan calls him “pathetic”; R2 and 3PO find him “odd”; Amidala doesn’t know what to make of him prior to her epiphany on Coruscant, and likewise Anakin seems to do a bit of side-eyeing until their in the same boat of being left out of everything in the city-planet; Qui-Gon only championed him because he values all life in the living Force, and even his patience wears thin. Hell, even his own people banished him upon pain of death for being such a pain in the ass.

And yet – every major good turn in the plot is either directly or indirectly the result of Jar Jar doing something. Jar Jar allowed the Jedi to reach the queen in time. He momentarily blocked R2 from going up on the hull of the Nubian allowing him better positioning for the escape. Amidala’s aforementioned epiphany was due to an offhand comment by Jar Jar. General Binks caused the most damage during the diversionary battle. Most importantly, Qui-Gon would have completely ignored little Anakin had the boy not been there to rescue a hungry Gungan from an especially dangerous Dug.

It’s clear the message here is reinforcing Qui-Gon’s rather Taoist philosophy that everything in life has value and is useful, no matter how valueless and useless it may appear. For me, who knows what it’s like to be the clumsy awkward kid that just wants to do well but only seems to screw up and irritate people, it makes Jar Jar endearing. I empathize and identify with the poor schmuck, and just want to give him a giant hug. And he does genuinely make me laugh.

The real tragedy is that I suspect many Star Wars Fans know this feeling, but rather than empathize they are in denial and rage against anything that reminds them of it – hence the Jar Jar hate. Oh, and also tragic is that lesson of “use for the useless” being learned by Palpatine in time for Clones…

Senator Binks, that’s a really great observation. I’ve never really thought much about what you’re saying, re the Taoist philosophy. But that’s precisely the kind of thing Lucas would do.

I actually don’t hate Jar Jar. He’s not one of my favorite characters by any means; but I never had that much of a problem with him. And actually the Clone Wars made me appreciate him a lot more too.

I have to admit though that I’ve never heard anyone ever say TPM is their favorite film. It’s refreshing to hear you say that – refreshing to know that someone regards it that highly. I’ve always loved the film for its broad qualities.

Thank you. Phantom really is just everything I love about movies and what they can do in one glorious package. I recognize some films may be “better” in certain technical aspects, and art is 99.99% (repeating of course) subjective, but no other film makes me as consistently happy from opening fanfare to closing credits.

Also, I apologize for the grammatical errors. Writing this on mobile, and autocorrect has a nasty habit of changing my words.

Actually, when you say it makes you ‘happy’, i totally get what you mean. TPM is probably the ‘feel-good’ movie for me too. As a movie I much prefer ROTS; but ROTS is incredibly grim and depressing, whereas TPM is more ‘fun’ to watch.

I actually vividly remember how much of a ‘positive’ feeling I used to get just from the Anakin ‘tone poem’ teaser for TPM – do you remember that?

By the way, I only discovered your site recently and have been enjoying going through some of the posts.

I actually cited this article in an essay for the college English course I’m taking now. Your opinions and analyses were very helpful in proving that the main reason people don’t like the PT is because of bias. I agree with your arguments completely, and actually found some that my friends and I can use the next time we end up in a debate with our other friends about whether the Prequels are “good movies” or “trash”. So, thanks.

You’re welcome, Karic Orynn. I’m very tired of the prequel-bashing, and I take every chance I can to defend George Lucas, who I regard as a genius.

Articles and analyses of this kind are shockingly rare; it seems as though many people really are afraid of having an opinion conflicting with the reactionary short-sighted narrative against the prequels. I entirely agree regarding the podrace and duel of the fates sequences; two of the 5 best action sequences of the saga without question. I really like the “stately” manner of camera composition in this film especially. And the fact that it lacks a “traditional” protagonist is actually one of my favorite things about it; it gives it a more detached, mysterious, unpredictable feel (especially with the closest character to a protagonist dying in the end), of being swept along for the ride in a completely different world, just getting a glimpse of it. The seemingly out of place humour elements I often attribute to an interpretation that each of the prequels is seen through the lens of Anakin (childlike here, as a moody young petulant teenager with his first crush in Ep II, and as a conflicted young adult with too much responsibility thrust upon him in Ep III). I also agree regarding the locations. Ep I is more purely transportive in the sense of seeing how another world works than any of the saga, and the art design is incredible. Seeing Otoh Gungah for the first time in theaters was chilling, and led to a long fascination with both architecture and underwater construction and pool designs. The creatures in the planet core are still some of the best creatures in film as well. And Qui-Gon was a fascinating character, truly monk-like in the way I imagined the most pure Jedi to be, fatherly, trusting, meditative, but a maverick to the corrupting order. I rate Ep. I as my second favorite of all the sage even now after Revenge of the Sith.

Thanks very much, Zihark.

Yes, I think a lot of people just don’t want to be seen to like a film that the Internet consensus insists is terrible.

There’s so much scope and scale and brilliance in Episode I, even though there are flaws too. Lucas is so underrated as an artist and especially as a visual artist – the way he frames scenes, the complete way he conceives of images and sequences, the way he does his establishing shots, etc. Ep1 is full of that – and it gets completely overlooked.

I think most people now are unable to get subtleties in films; and there also seems to be an intolerance of filmmakers who do things their own way; it’s as if everything needs to be standardised and generic in order for it to be deemed ‘a success’ or for it to ‘connect with its audience’, etc. But I’ve always liked and respected that Ep1 and the prequels completely do their own thing. These films have much more in common with old, historical epics like Ben Hur, Spartacus and Cleopatra than they do with modern, generic blockbuster cinema. That’s something most people don’t seem to get.