While no one is likely to dispute Muhammad Ali’s claim to the title of Greatest Sports Star of All-Time, it was his potency and relevance as an inimitable cultural and social icon that many more people beyond the realm of sport will always remember him for.

There has been no one else in the world of sport – and practically no one in the world of entertainment – who was so significant a symbol and so loved in so much of the world and so far beyond his trade; in Britain, in Latin America, across Africa and Asia, from Louisville to London, Rio to Pakistan, he was adored and celebrated like no one else before or since.

When he went to Zaire in 1974 for what is regarded as the greatest sporting event in history – the famous ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ title fight with George Foreman (which I have watched several times in its entirety, despite not even being a fan of boxing) – he was mobbed by locals who chanted and sang and who celebrated him as their own hero.

“Muhammad Ali was not just Muhammad Ali the Greatest… he belonged to everyone,” the late Maya Angelou summed it up in the 2001 book Muhammad Ali: Through the Eyes of the World. “His impact recognizes no continent, no language, no color, no ocean.”

Nelson Mandela has said that when he was serving out his imprisonment on Robben Island, Muhammad Ali gave him hope that the walls would some day come tumbling down.

He was a powerful symbol *everywhere* and his cultural stature was enormous. In 1991, during the Gulf War, it was Ali who was sent to Iraq to meet Saddam Hussein to try to negotiate the release of American hostages.

Despite all those unmatched moments of sporting triumph that allowed him to irrefutably fulfil his own immodest boast of being ‘the Greatest’, and all those bursts of verbal eloquence and free-style poetry or those golden interviews he gave with the late David Frost or with Michael Parkinson, for some, Ali’s greatest moment might not have been in the ring at all, nor in the field of light entertainment; but in his defiant refusal to be inducted into the armed forces during the Vietnam War.

Flatly stating that he had “no quarrel with them Vietcong”, Ali proceeded to take one of the most memorable anti-Establishment, anti-war stances in history.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he complained with true Ali flourish and melody. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father…. How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

It is one of the most beautiful (and justified) diatribes you will ever hear. We can see it now as a righteous, entirely justified reaction; but most people at the time saw it differently.

Most people in America at that moment saw the Vietnam War as justified and Ali as an unpatriotic upstart and troublemaker.

His stance cost him greatly. Ali was sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine, though he remained out on bail while he appealed. He was also stripped of his title as world champion – which seemed more vindictive than anything else. He would later win it back in what would be one of the greatest moments in entertainment history. But for now, he was systematically denied a boxing license in every state and was stripped of his passport.

Unable to fight from 1967 to late 1970, he was essentially robbed of what should’ve been the best part of his career (aged between 25 to almost 29). By 1971 the Supreme Court overturned his conviction, but Ali had already paid the price for his defiance. In reference to this cost, his trainer Angelo Dundee said way back in 2000, “One thing must be taken into account when talking about Ali: He was robbed of his best years, his prime years.”

“I had the world heavyweight title not because it was given to me, not because of my race or religion, but because I won it in the ring,” Ali himself had later said. “Those who want to take it and start a series of auction-type bouts not only do me a disservice, but actually disgrace themselves…”

But Ali’s bold defiance “rang serious alarm bells,” Noam Chomsky later wrote, “because it raised the question of why poor people in the United States were being forced by rich people in the United States to kill poor people in Vietnam. Putting it simply, that’s what it amounted to. And Ali put it very simply in ways that people could understand.”

What shouldn’t be overlooked from our present vantage is that Ali was speaking at a time when general public support for the war in Vietnam was still very high, with the more popular protest movement having not emerged yet. But a month after Ali’s brutally honest reaction to the army, support for the war had slipped below 50 percent for the first time since the hostilities had begun, indicating his highly publicized act of rebellion was already starting to influence opinion.

For some time, Ali remained under public pressure to change his stance, to apologise for his statements, or even just to enter the military for entertainment services (performing for troops, endorsing the war, etc, and essentially becoming a Black Bob Hope). He refused.

Attending a rally for fairer housing in Louisville, Ali expanded further on his position: ‘Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality… So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.’

And as this account highlights, even ‘some of his allies turned against him.

The Nation of Islam, the same religious group that anointed him Muhammad Ali, disavowed him for his style of active resistance, according to Dave Zirin’s A People’s History Of Sports In The United States. Jackie Robinson, an athlete and activist himself during his playing years and beyond, ripped Ali for disappointing black war veterans, and by and large, black soldiers agreed with Robinson: Ali was being too radical.’

It is remarkable, with hindsight, how much Ali’s position was seen as ‘radical’ even by some of those who might otherwise have been on his side in other regards.

We now know that in 1963 (fifty days before his assassination), John F. Kennedy had ordered a complete withdrawal from Vietnam. So Ali – ‘the radical’ – was, in 1967, simply refusing to participate in a foreign war that a US President had already tried to withdraw from four years earlier.

Ali’s eloquent snubbing of the army occurred on April 28th 1967. This was around the same time Robert F. Kennedy (pictured above) was developing his three-point plan to end the war in Vietnam.

In that context, Ali was hardly being all that ‘radical’ at all.

On June 4th 1968, Robert Kennedy was himself assassinated to prevent him being able to run for the presidency – and the Vietnam War raged on.

Eventually, of course, protest against the War in Vietnam would become much more pronounced and widespread and would not be seen as a racial issue at all, but a moral one.

But Ali, who at that time was regarded a ‘radical’ and not interested in assimilation or in appeasement of the mainstream establishment, was able to be more honest and blunt than many others were willing to be. In fact, it is believed by many that Ali’s radicalism was what pushed the much less radical Martin Luther King to begin speaking out against the war. King, who had been reluctant to address Vietnam out of fear of falling out with the Lyndon Johnson administration (and thus losing White House support for the Civil Rights movement), was forced by Ali’s defiance to the draft to begin addressing the war.

It is recorded also that King had warned the White House that failure or delay in accommodating the Civil Rights movement would lead to an escalation of radicalism and of support for people like Ali, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam.

While it could be argued that those who work patiently and temperately within the system (or at least in cooperation with the Establishment) might be better placed to bring about change and progress in the long-run, the argument can also be made that it is the radicals and the hotheads who force things to happen and who engender more of a sense of urgency: Ali could be cited as a prime example of that in the broader context of the Civil Rights movement, even if he was ideologically at odds with King and the others at the time.

The point is that Martin Luther King, for all his eloquence and all his commitment to doing things the Gandhi way, might not have accomplished anything had the mainstream, conservative establishment not also been genuinely unsettled by more ‘radical’ figures like Malcolm X or Muhammad Ali.

Dave Zirvin portrays that moment in these terms; ‘For an emerging movement that was demanding an end to racism by any means necessary and a very young, emerging anti-war struggle, he was a transformative figure. In the mid-1960s, the anti-war and anti-racist movements were on parallel tracks. Then you had the heavyweight champ with one foot in each. Or as poet Sonia Sanchez put it with aching beauty, “It’s hard now to relay the emotion of that time. This was still a time when hardly any well-known people were resisting the draft… and here was this beautiful, funny poetical young man standing up and saying no!’

What Ali did was not just at significant cost to himself and his career, but could’ve potentially been endangering his life.

But he took an uncompromising stand, and more than that he was using his position as heavyweight champion of the world and an immensely popular celebrity to draw people’s attention to an issue and to re-frame the paradigm of the Vietnam War in a powerful way for a lot of people.

_____________________

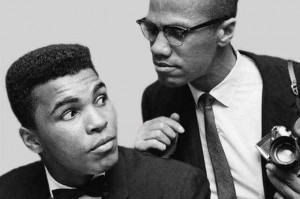

In terms of his general ‘radicalism’ in the sixties, his position on race relations and in particular his relationship to Malcolm X, and how he was seen as an extremist and was immensely disliked at the time – by both the white, conservative establishment and even sections of the Civil Rights movement – that could really constitute a whole separate article.

Which I would be keen to come back to; after I’ve finished re-watching When We Were Kings for the seventh time and all Ali’s interviews with Frost and Parkinson again.

In fact, thinking about Ali’s three-decade struggle with Parkinson’s from the mid-eighties onward, one of the saddest things about it is that so powerful and entertaining a communicator and poet was rendered virtually unable to speak for the final third of his life. He was robbed slowly of his ability to communicate and we, in general, were also robbed of the opportunity to hear more of him.

But Dave Zirin, writing on The Nation yesterday, aptly summed up the enduring importance and power of Ali as a cultural, social and political icon. ‘Full articles can and should be written about his complexities: his fallout with Malcolm X, his depoliticization in the 1970s, the ways that warmongers attempted to use him like a prop as he suffered in failing health. But the most important part of his legacy is that time in the 1960s when he refused to be afraid. As he said years later, “Some people thought I was a hero. Some people said that what I did was wrong. But everything I did was according to my conscience. I wasn’t trying to be a leader. I just wanted to be free.”

Meanwhile, the title he’d had stripped from him for his refusal to enlist in the army was regained a few years later the hard way – through fighting his way back to reclaim what was his and becoming Champion of the World again. Which is pretty much what he will remain forever.

__________________

The Louisville Lip – may he rest in peace.