It’s an extraordinary fact of Pakistan’s turbulent history that no Prime Minister has ever been able to see out a full term.

The reasons for this differ from case to case: corruption, criminal charges, military coups, etc. In the case of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, probably Pakistan’s most popular leader since its founding, he was literally removed from office and put to death by a military dictator.

In the case of his daughter, Benazir Bhutto (with whom Imran Khan was personal friends), it was assassination.

In the latest case, the case of Imran Khan himself, it was a ‘vote of no confidence’, which Khan apparently lost: leading to his removal from office.

Or… it was, as Khan himself claimed, a Washington-backed ‘regime change’ to oust his government and install what he called a ‘foreign imported’ administration.

So let’s look at this: both in terms of the current events and in terms of some of the historical context, both of which feed in to each other.

The historical context is really important, in order to understand Pakistan’s enormous problems. But let’s focus on the present controversies first.

We’ll also get to the fact that Imran Khan just met with Vladimir Putin in Moscow – in a state visit that was widely condemned by the US and the West. And that this event clearly formed the backdrop to the demise of Imran Khan’s term as Prime Minister.

I’ve never developed a fixed or particular opinion of Imran Khan’s leadership: some things he has done or advocated, I’ve disagreed with, while other things I’ve seen as positive. However, what he has always come across as is the most sincere Pakistani leader in decades, one of the most eloquent national leaders on the world stage, and someone capable of representing Pakistan’s sovereign interests in a way that has been sorely lacking for a very long time in the country’s string of failed leaders and dysfunctional or corrupt administrations.

His critics see him as a manipulative populist, who has presided over an ineffective administration that has failed to live up to its promises since he came to power in 2018. Some of this might be true,

What is abundantly clear, regardless of what you think of Khan as a leader, is the enormous popular support he enjoys.

Tens of thousands took to the streets in cities across #Pakistan in protest against the removal of former Prime Minister Imran Khan & rumored US efforts of regime change. Take a look & listen to their chant.pic.twitter.com/WgFJmhDije

— Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) April 11, 2022

This is evident from the sheer scale and fervour of the protests that have broken out in Pakistan following his removal from office. You don’t see rallies on this scale unless the leader in question has genuine public support. And very few Pakistani leaders have ever enjoyed that kind of mass support.

Khan’s substantial popular support makes sense, irrespective of actual politics or policy: he was, after all, a sports icon and legend in Pakistan long before he entered politics. Moreover, scores of Pakistanis (especially the youth, who are Khan’s most loyal supporters) believe Khan’s assertions – made prior to the no confidence vote – that the United States was trying to remove him from office: they therefore see Khan’s removal (rightly or wrongly) as a foreign-influenced plot and a violation of Pakistani democracy and self-determination.

Whether this claim was true or not is difficult to know, of course. But let’s give it a go.

Khan’s claims of a conspiracy may have been an act of desperation to avoid the no confidence vote – which is what his critics say it was.

What’s curious, however, was his claim that he had access to a letter involving an embassy official and perceived threats from the US: and which proved that such a conspiracy existed. He was prevented from making that letter public by the Supreme Court: which is in itself curious.

If Khan was lying about the existence of such a document, it’s odd that the court would ban him from making the document public.

According to media sources, ‘the letter was based on the minutes of a meeting of a Pakistan embassy official with officials of the host country… The details of the meeting were sent by the Pakistan ambassador in that country to the Foreign Office as part of internal diplomatic communication, which showed that the host country was not happy with the policy of the Pakistan government on Ukraine and its ties with Russia…’

The ‘host country’ being referred to is the United States, Khan said.

Attempting to stave off the no confidence vote, Khan had dissolved parliament and called for snap elections: on the grounds that parliament and the imminent vote were both compromised by foreign interference. But the Supreme Court ruled this action unlawful and allowed the vote to go ahead.

Given the apparent popular support for Khan, it seems likely that a snap election would’ve worked in his favor: and would’ve made it more difficult for the political opposition to remove him from office. It should also be remembered that Khan came to office with a massive election victory four years ago.

While the court’s ruling that the dissolving of parliament was unlawful is true, according to the ins and outs of the law, there is also a counter-point that can be made to say that the removal of a duly elected Prime Minister and the swearing in of an *unelected* leader (not to mention one who is himself under criminal investigation) could be considered just as questionable.

Certainly, however the legal justifications can – and are – being shaped and argued, there is a perceived lack of legitimacy here, as far as all those thousands and thousands of people on the streets are concerned.

Let’s also bear in mind that it was also the Supreme Court that legalised the military’s execution of the democratically-elected Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979: so, as much as the judiciary and its rulings are of course essential to the functioning of any state and the rule of law is sacrosanct, it doesn’t mean that said institution or its rulings are always just or always in the national interest.

Washington has of course denied any involvement in what’s happened in Pakistan.

But Imran Khan has been seen as one of the most openly anti-American leaders in Pakistan since the days of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. He has also been a fierce opponent of everything Pakistan was involved in during the US-led War on Terror – as well as the enormous price the country has paid from that entire period (both politically and in terms of sheer loss of life).

Khan, for his part, claims not to be anti American at all: but simply opposed to Pakistan being dictated to or controlled by foreign governments and being free instead to make its own decisions. The recent interview Khan gave to RT’s Oksana Boyko (during his ‘controversial’ state visit to Moscow last month) in fact lays out his disposition very clearly. I will include that video here at the end of the article, as it is a very good interview.

And one of the very obvious triggers that might’ve prompted any hypothetical Washington-backed plot would’ve been Imran Khan’s refusal to play ball in terms of the sanctioning of Russia over the conflict in Ukraine.

Which is clearly what is implied by the supposed contents of the ‘foreign conspiracy letter’.

This was something the United States was openly angry about.

Imran Khan not only refused to sanction (or even condemn) Russia for its Ukraine operation, but Khan himself made the extraordinary gesture of making a state visit to Moscow to meet with Putin – right in the midst of Western sanctions being implemented and the Russian operation in Ukraine unfolding.

Without doubt, this was seen as a serious act of defiance: by the leader of a country that has traditionally been closely allied to (or a vassal state of) the United States.

Khan was adamant about Pakistan having the right to decide its own foreign policy: he complained at the time about the US and the West thinking Pakistan was its “slave” and was simply expected to fall in line with Western policy.

There’s no question that Khan making a state visit to Moscow right in the midst of the Russian invasion into Ukraine was a ballsy move: and a major provocation. The implications in Pakistan were also that the military – which has mostly been friendly towards Khan until recently – wasn’t happy about Khan’s perceived anti American actions and apparently provocative trip to Russia.

That the US would be involved in some move to remove Khan from office at this point in time isn’t illogical: even if there isn’t any clear proof of it.

What Khan alleges is that various political figures in Pakistan were simply bought off as useful idiots to facilitate the vote of no confidence. Needless to say, this would include elements of Pakistan’s political elites.

It should be borne in mind, however, that if the military was by now no longer favourable towards Khan’s continuation as PM, then Khan was always going to be in trouble. But even given all of the interests and alliances apparently ranged against him, it is worth noting that the vote against Khan only barely got the numbers it needed. It was hardly unanimous.

It’s also worth noting that Shehbaz Sharif– the man being sworn in to replace Khan as Prime Minister – is from one of the country’s political ‘dynasties’ and is in fact the epitome of Pakistani politicians’ long history of corruption.

Sharif is the brother of two-time Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif – a man who was removed from office due to extraordinary levels of corruption and has resided in-exile in the UK ever since (to avoid arrest in Pakistan). Nawaz Sharif was in fact barred from ‘ever holding office again’.

So now his brother is taking over instead. Shehbaz Sharif has also lived in the UK: and is, extraordinarily, the ongoing subject of a criminal investigation for major financial fraud *even as he is being sworn into office*!

I mean, you couldn’t make this shit up.

The optics are very poor. While Khan has his critics and his failings (and some of his own inner circle have been accused of significant corruption), Khan came into power on a popular wave probably not seen in Pakistan since Benazir Bhutto, with one of his main stated agendas being to clean out Pakistani politics of the endemic corruption that has blighted the country for so long.

And, regardless again of whether you like him or not, he has been removed from office without any popular/public mandate – and replaced by an unelected member of Pakistan’s elite, who should’ve himself been facing criminal charges even before he took office.

Some media even shrugged off the popular opposition to Sharif’s installation by saying ‘Beggars can’t be choosers…’

This is also slightly reminiscent of events in Brazil a few years ago (covered here), where Dilma Rousseff was removed from government on the grounds of ‘corruption’, while most of the opposition politicians prosecuting her were themselves the subject of ongoing corruption cases – a brazen example of a country’s wealthy elites and corrupt establishment politicians using the courts to force an inconvenient leader from government.

In that incident too, there were certainly implications of the plotters having tacit approval from Washington.

But none of this means Washington was involved in the ousting of Khan. Those pooh-poohing Khan’s ‘conspiracy letter’ claims argue that the contents of the text merely reveal American displeasure at Khan’s Russia/Ukraine stance – and cannot be construed as in any way being evidence of an actual ‘regime change’ plot. Khan, they argue, is simply blowing the document out of proportion in order to inflame his supporters and paint himself as the victim of a conspiracy: while also trying to weaponise the widespread anti-American feeling in much of the country.

Which may well be the case. He is, after all, a politician.

But if what has happened in Pakistan *isn’t* a Washington-backed plot, it’s nevertheless a turn of events we can nevertheless assume Washington is comfortable with.

It’s just as likely that various figures in the judiciary and the political opposition might’ve been collaborating with both foreign interests and the ever-present Deep State or ISI to push things in this direction. Certainly since Khan assumed office, corruption cases or charges against various politicians have left the political classes feeling insecure and under too much scrutiny: so some of the motives for moving to remove Khan would’ve been predictably self-serving.

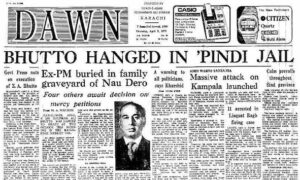

Still, given some of the previous fates of Pakistan’s elected officials, Khan has almost gotten off easy. Which is to say it could’ve been worse, if we cite the fate of the unfortunate Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

And this is where we have to look at some key aspects in Pakistan’s tumultuous and painful history: to see that there are certainly interesting resonances or parallels that can be drawn between those defining traumas in Pakistan’s history and the present state of affairs.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto remains Pakistan’s most popular leader to date: a figure whose judicial murder is still mourned by thousands every year in Pakistan. Among other things, Bhutto had been unhappy about Pakistan’s relationship with the US and was pushing for the country to be more independent. In essence, Bhutto – who was more or less a secular leader and a moderniser, as well as a left-leaning politician pursuing policies centered on social justice – was committed to preventing Pakistan being a puppet state under foreign dominance.

We can see the echoes of this in Imran Khan’s recent statements about Pakistan not being the West’s “slave”. Khan, like Bhutto, has talked frequently about Pakistan being free to pursue its own foreign policies, for example: which was, again, a big part of why he refused to denounce Russia and why he chose to go to Moscow at what was – through Western eyes – the worst possible moment.

Suspicions have long existed in Pakistan that Bhutto’s removal from office – and his execution on the orders of the military dictator Zia-ul Haq – might’ve been at least tacitly sanctioned by the US.

Declassified CIA documents at the very least show that the US was fully aware of the likelihood of Bhutto being put to death.

All of this generation-defining crisis in Pakistan stemmed from Bhutto and the Pakistan People’s Party’s main opposition – primarily an alliance of conservative Islamist parties – refusing to accept Bhutto’s sweeping majority win in elections and accusing him therefore of vote-rigging. What ultimately followed, along with Bhutto being put to death by hanging in 1979, was years of martial law and military dictatorship.

It is worth noting, historically, that the dictatorship’s friendly disposition towards religious conservatives and fundamentalists was something that directly benefited the US in the Cold War: because the Pakistani military was the major facilitator of the Mujahideen holy war in Afghanistan against the Soviets, which was of course a major part of the US’s anti-Soviet policy at that time.

We won’t bother to get into the pros and cons of the US or Pakistan’s Afghanistan policies here, as that’s a whole separate subject. There are good arguments for why the US supported the Mujahideen’s justified war against the Soviet invaders, as well as good arguments for how the whole thing ended up being a disaster for everyone in the long run.

None of this proves – or means – that the US was directly involved in the removal of Bhutto from office or in his execution: but it’s easy to see how the US would quietly sit the matter out and be perfectly happy for the military to put Pakistan’s duly-elected (and most popular) political figure to death.

Bhutto himself had said he was being targeted by what he’d called the two hegemonies over Pakistan’s fate – the internal one, being the military and the elites, and the external one being the United States.

It is entirely possible – and would be somewhat in keeping with the historical context – that Imran Khan may have been ousted by the same marriage of interests: albeit in a less horrible manner.

This video by TCM Originals lays out some of the reasons for suspecting the US of having quietly sanctioned the moves against Bhutto; including elements that are strikingly similar to the narrative that Imran Khan has been putting forward in the last few weeks – such as perceived threats from the US embassy and even reference to a letter or document that Bhutto was planning to expose.

These obvious parallels suggest either that a very similar series of events has genuinely unfolded or that Imran Khan has actually fabricated – or at least carefully framed – his own narrative of these events so as to deliberately resemble the ousting of Bhutto forty years ago (knowing, of course, how much the injustice done both to Bhutto, and by extension the Pakistani people, has resonated in the public consciousness for so long).

It’s difficult to tell for sure which of those is the truth.

But the fact that this vote of no confidence came immediately on the heels of Imran Khan’s visit to Moscow seems significant.

At any rate, conspiracy or no conspiracy, compared to what befell Bhutto, Khan at least gets out with his dignity (and his life).

And he has the chance to run for election again in the future: now with the added potency of being perceived as the wrongfully-deposed leader by his massive support-base. Given that the newly-restored administration of Sharif and the Muslim League is likely to be mired in corruption (in keeping with both that family’s record and the country’s politics in general), as well as being viewed by so many as illegitimate and unelected, Imran Khan could be in a very powerful position going in to the next election.

However, the danger isn’t over for him.

If either (or both) the Pakistan Deep State (the ISI and the military) and foreign interests are no longer favourable towards Imran Khan, then him even running for office again could be dangerous, regardless of popular support.

Benazir Bhutto, for example, was assassinated in 2007, essentially to prevent her from returning to any sort of power in elections that were imminent. I won’t bother going into the convoluted web of conspiracy theories and allegations concerning her assassination here – as that would be enough to fill a War & Peace sized book.

But if Imran Khan has powerful enemies opposed to his holding office, then he will need to be very careful.

What is always clear is that Pakistan is an extremely difficult country to govern, and being Pakistan’s leader a remarkably difficult job. Whether this poisoned chalice dynamic is due to deep-rooted corruption within the country’s politics, or due to continuous external/foreign interference in Pakistan’s affairs, is never easy to distinguish.

Perhaps because it’s both.

__________________

__________________