A first century BC villa on the fringes of Rome is likely to be destroyed by a modern housing development.

And not just a first century villa, but the villa believed to have belonged to Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus; the historical character immortalised by actor Stephen Boyd in the 1959 epic Ben Hur.

The remains of the villa are along the famous Appian Way, the ancient Roman road out of the capital.

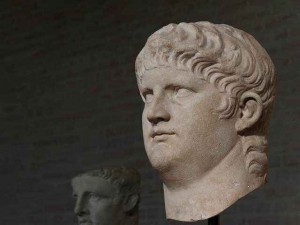

The Roman General featured both in the original General Lew Wallace book in 1880 and the classic Charlton Heston movie based on it; although the story’s principal character Judah Ben Hur was a fictional creation, Boyd’s ‘Messalla’ character (pictured above) was based on a real-world historical figure. Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus is believed to have played a significant role in the legendary and epoch-defining Battle of Actium, fighting for Octavian against the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. He was also believed to have been a highly connected Roman citizen, able to count the likes of Cicero, Ovid and Horace as friends or acquaintances.

The villa believed to have belonged to him is located close to two airports in the Ciampino area. There are plans to build multiple apartment blocks on the villa’s remains. The local council claims the site is only of “modest archaeological worth”, after seven statues were removed from the villa two years ago; they go on to say that the statues were the only significant feature of the site.

Only in a city as spoilt-for-choice as Rome is when it comes to historic sites could officials almost be forgiven for regarding something like the Corvinus villa as dispensable.

Archaeologists, however, are fighting to prevent the development plan, along with a local residents’ community. Alessandro Betori, a cultural heritage official, has insisted the entire area should be considered “a no-build zone”.

Of course it should; you can’t replace history. Once something like that is gone, it’s gone.

Sites like the Messalla villa, along with key historical sites all over the world, are part of our collective cultural and historic heritage, part of our collective identity. It is surely our duty to preserve such sites for future generations?

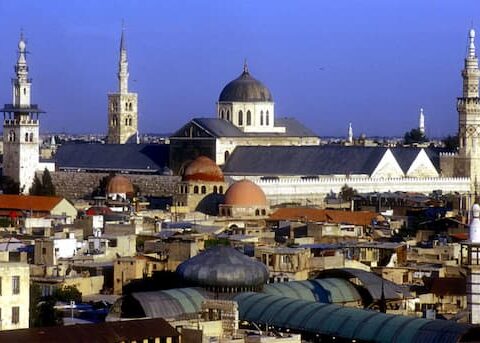

Unfortunately there are numerous reasons so many such sites fall into further ruin or come under threat from various modern factors; economic and corporate interests, the unrelenting pace of perceived 21st century building needs, and even war (as has been the tragic case in Syria, which has had so much of its rich, irreplaceable history destroyed in the passed three years).

The major problem in most cases is simply the austere economic times in Europe, meaning that spending has to be majorly prioritized; cash-strapped Italian authorities are simply struggling to foot the bill for the kind of preservation or restoration costs required for sites like the Messalla villa, Nero’s Palace in Rome, even parts of Pompeii.

One site undeniably of enormous historic and cultural value – the Mausoleum of Augustus – has been in a terrible state for years, having been vandalised, ransacked and built over for generations, eventually ending up as a haunt for prostitutes and a toilet for tramps. This was a site that once housed the ashes of not only Augustus, but Tiberius and Claudius as well.

That site hasn’t been open to visitors for a very long time; thankfully it has recently been rescued by Italian authorities able to secure the kind of funding needed to restore the site (which is intended to be reopened to the public in 2016).

But other sites will not be so lucky.

There’s the case of Nero’s extraordinary palace in Rome. Covered in gold leaf, it was once a majestic symbol of the wealth of Imperial Rome. The Domus Aurea is a sprawling complex of interconnecting dining halls, frescoed reception rooms and vaulted hallways perched on a hill opposite the Colosseum. But two-thousand years after its time, authorities in Italy were forced to launch an appeal for £25 million to help preserve the vast palace. A modern-day park sits on top of the site and has done major damage to the structure.

The danger of structural collapses means the enormous palace has been closed to visitors for nearly a decade; in 2010 the collapse of a section of roof renewed fears for the monument’s future.

Archaeologists from the Cultural Heritage Ministry recently announced plans to strip away the existing park, cutting down trees and removing the enormous amounts of soil in order to replace it with a landscaped garden designed to protect the palace below from more damage. The project is expected to take four years, after which the palace will be reopened to the public.

The plan appears to be sound; the problem was that the government had no money to donate to the project, so archaeologists were forced to take the begging bowl to private companies or corporations that might be willing to step in and pick up the tab.

It’s a sad state of affairs; and perhaps a sign of the economic times we live in.

Nero’s Domus Aurea is/was a genuine archaeological wonder. Five years ago archaeologists found what they believe to be the remains of a banqueting room that was able to rotate – a novelty the unhinged, fire-loving Emperor had concocted to impress his many guests.

The 50ft-wide dining area was underpinned by a broad pillar and a mechanism that allowed it to slowly rotate – therefore correlating with an account by the Roman historian Suetonius, who described a dining hall that revolved “day and night, in time with the sky”.

Sites of this type are our living, tangible connection to human history and are of immense, immeasurable importance. In the case of the Messalla villa, probably not regarded on the same level of importance as the Domus Aurea, I fear it may not be saved; that it will become one of the sites lost to us.

Which is lamentable. It’s one thing to be wistful about great historic sites no longer available to us (the Library of Alexandria, for example), but to have sites that are right here in our possession and to watch them literally built over in our own time is, culturally speaking, a tragedy.

The same thing applies, on an even bigger scale, to what has happened to the historic heritage of places like Syria and Iraq in recent years, both of which are absolute treasure-troves of immense archaeological value, both countries full of major historic sites spanning multiple eras (Sumerian, Babylonian and Mesopotamian, Roman, original Gospel era Christian, Islamic, etc), all of which has been severely at risk from both warfare and looting in recent years. There have been stories even this week of Islamic State fighters selling off Iraqi historic artefacts on the black market to raise money for their barbaric activities.

In the case of Syria, which is virtually unparalleled for its breadth and diversity of historic heritage, the full scale of the damage done to that country’s unique cultural landscape won’t even be properly known until after the Civil War is ended.

Returning to the subject of the Messalla villa in Rome; on a personal note, the fictional version of Messalla is one of my favourite all-time film characters, unforgettably brought to life through Stephen Boyd’s performance in the 1959 film; that character also has, in my opinion, the greatest of cinema’s death scenes (“The race goes on, Judah…”).

Sadly the historic villa associated with the character may soon have a death scene of its own.