This year’s Christmas piece was originally going to be like last year’s and focus on an element of the Nativity tradition; instead, given current events and the popular reaction to them, I decided to go with a different subject – specifically, Islam and Christianity.

There is now, perhaps inevitably, a growing trend in some sections of Western commentary to see things in terms of a Muslim/Christian divide; or the idea, more specifically, that Islam is a threat or enemy towards Christianity.

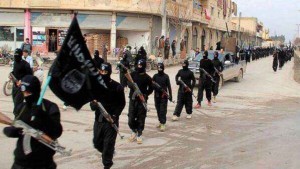

To some extent, there is a sub-sect within Islam – a radical, extremist ideology – that probably could be described as a threat to Christian interests or ‘Christian values’; but that same sub-sect is also the same threat to mainstream Muslim communities and ‘values’ too – probably more so, in fact.

An attack like we just saw in Berlin – perceived by many as an attack on ‘Christmas’ or on Christianity – could on some level be taken that way (if we assume, for the moment and for argument’s sake, that it wasn’t a false-flag, even though it probably was); but it really was just an attack in general on the West. The same, relatively modern ideology that drives such acts of terrorism is also responsible for countless attacks on mosques and Muslim sites across the Middle East too, where it is essentially ‘Muslim on Muslim’ crime, if you pardon the expression.

I’m not denying that there are some serious issues in parts of Muslim communities in some places in Europe – which seems to be a problem of integration and identity, exploited by radicalism – and that work needs to be done. But the idea of the Muslim/Christian divide seems like a patently false construct that isn’t borne out by history: and before we read any more deliberately divisive articles about the ‘attack on Christmas’ (or bullshit ‘Alt Right’ revisionist history concerning the Crusades), we really should get back a proper perspective.

And I write all of this as someone with no particular axe to grind either way: I write this as a general student of history and not as someone invested in any religion.

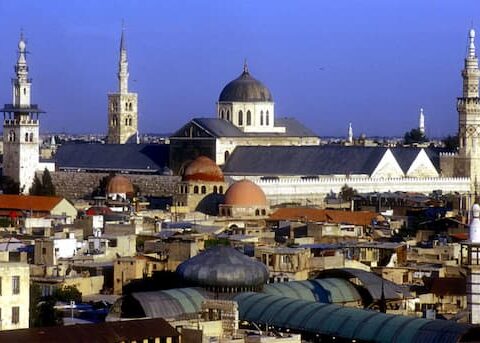

The real dynamic between Christianity and Islam has to be observed first in the Middle East.

The ‘Crisis of Christianity in the Middle East’ was rightly being made much of two years or so ago; but it is worth putting these events in their proper context. Beginning with correcting the false premise that ‘Islam’ and ‘Christianity’ cannot co-exist or that Islam somehow sees Christianity as an enemy. In reality, the collapse of inter-faith harmony in the Middle East doesn’t have its primary basis in religion, but is part of the broader collapse of the Middle Eastern cultural and socio-political fabric, primarily following the invasion of Iraq and expanded by the covert war on Syria.

In 2003, before the US-led invasion happened, there were an estimated 1.5 million Christians living in Iraq. Today, experts say, there are fewer than 400,000.

The ISIS rampage through Iraq’s Nineveh plains forced an exodus of the Chaldean Christians and other minorities from areas in which they had co-existed for nearly 2,000 years. Attacks targeting Christian communities across the region were substantial, including in Baghdad and Mosul, the persecution of Egyptian Copts in post-Mubbarak Egypt, the occupation of the ancient Christian town of Maaloula by the Western-backed Al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, and the mass eviction of Christians from their homelands in Nineveh in Iraq.

Propagandists love to spin those events as indicative of some kind of prevalent Islamic attitude towards Christians: this, however, isn’t borne out by history in general, particularly the twentieth century. The No.1 reason for the societal/cultural fragmentation and collapse in the Middle East is the sudden collapse – in just a few years – of the secular, Arab Nationalism that defined states such as Iraq, Syria and Libya prior to war or foreign intervention.

In Iraq, for example, there was never any persecution of Christians under the Ba’athist party – even if there was general oppression of the general population. Indeed Saddam Hussein’s Foreign Minister, Tariq Aziz, was famously Catholic.

Aziz, the stories go, used to dismay foreign dignitaries by breaking into ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ in Aramaic, the language of Jesus.

There has never really been a major sectarian divide between Muslims and Christians in the Middle East beyond the medieval Crusades (which, let’s remember, were started by European Crusaders). While there were doubtless instances of tension or scattered incidents of religious dispute (particularly in countries that have been flooded with low-class ‘madrassas’ or Wahhabi-funded literature, such as in parts of Pakistan), places like Syria were for the longest time fairly well balanced in their rich cultural/religious tapestries.

Writing in the 1920s, for example, British historian Richard Coke wrote the book Baghdad: The City of Peace, recalling “the magnificent scale on which the Christian festivals were celebrated in the churches” and “the many Muslims attending the services, and it was, we are told, a popular custom at holiday times to repair to one of the country monasteries with which the neighborhood abounded, ‘for dancing, drinking and pleasure-making.’”

It is also widely under-appreciated that since around the 19th century, Christian Arabs were playing a central role in defining the secular Arab cultural identity that would later be adopted in Iraq and Syria. Many of the founders of secular Arab nationalism (of the kind that would later be adopted in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and Gaddafi’s Libya) were men like Michel Aflaq – a Greek Orthodox Christian from Damascus, who is widely regarded as the founder of Ba’athism.

Syria prior to the Civil War was a rich tapestry of diverse ethnic and religious groups, sheltered by Syrian government and society; groups that had all but disappeared elsewhere in the region. As well as the Alawites there were large minorities of Kurds, Armenians, Circassians and Druzes, as well as more arcane groups such as the Yezidi, the Mandeans (a Gnostic sect descended the from followers of John the Baptist) and the Urfalees (Syrian Orthodox refugees from the early Christian centre of Edessa). There were also Sufi brotherhoods, the preservers of culturally important musical and mystical traditions and the vanguards of the more mystical side of Islam.

All of the sectarian and inter-faith bloodshed that has happened in Syria in recent years has been a sole and direct consequence of the proxy warfare that has unfolded since 2011 – most of which has been orchestrated by foreign powers and entities.

Post-war Iraq has suffered the same – and probably worse – with its cultural make-up completely wrecked. This current sectarianism and violence therefore isn’t something that has grown inherently out of Islam or the long history of Muslim/Christian relations – but of collapsed states and widespread disorder due to geopolitical interference.

All of this propaganda perception of a Muslim/Christian divide is entirely post-Iraq War and is a consequence of the destabilization of the region, which has served to displace Arab intellectualism and disempower Middle Eastern progressives and secularists, allowing toxic and extremist ideologies (mostly inspired from Saudi Arabia and based on a sect that only goes back a hundred years or so) to gain a foothold and to violently change the cultural fabric of societies where they previously weren’t allowed to have much influence.

The result has been an avalanche of polarisation, which began in the Middle East and parts of the Muslim world elsewhere and is now being echoed in Europe and the West.

Even in Gaza and the West Bank, Palestinian Christians were reported from a few years ago to have been emigrating, increasingly caught between the Zionist extremists of the pro-settler Israeli government and the more and more radicalised elements of the Muslim Palestinian community. Where in the past, Palestinians had zero sectarian issues and were united in their national (rather than religious) identity, the increasing extremism of Hamas (the result of the parallel extremification of Zionist nationalism and lack of international intervention) has been changing all of that – ultimately to the lasting detriment of the Palestinian cause.

This course of events, however, has suited the more extremist right-wing Zionists very well: because, by slowly turning what used to be a secular Palestinian national movement (that included and unified Christians, Muslims and atheists) into something more easily caricatured as an extremist Islamist movement, the Israeli right-wing can justify its own extreme policies and more easily discredit Palestinian resistance to outside observers.

As much as divide-and-conquer propagandists may try to suggest otherwise, there isn’t any real, inherent Islamic enmity towards Christianity.

The more one understands or examines history – which is what most scholars and experts do, as opposed to relying purely on current affairs and contemporary biases – the more it is evident that Muslims and Christians have largely lived in peace with each other, including Christians living within Islamic societies. If anything else was the case, then the Christian holy sites in Jerusalem simply would not have remained Christian for all these centuries.

Nor would Christian communities and sites in Syria and Iraq have remained unscathed for centuries prior to the current conflict(s). It is famously known, for example, that one of the holiest sites in Christianity, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem – held by Christians to be where Jesus was buried and rose from the dead – has been under the continual custodianship of Muslim families since at least the 12th century to this day and preserved an an entirely Christian site, in part because differing Christian denominations have rival claims to the site.

This culture of tolerance was even brought to Southern Europe for a long time, where Muslims, Christians and Jews were living in peace and the science, agriculture, political science and the arts of the time were able to flourish, echoing what historians regard as Islam’s ‘Golden Age’ (principally under the Abbassid Dynasty, from roughly the mid 8th century until the mid 13th century, and which any number of historians credit with having carried the torch for civilisation at a time when Europe was languishing in the post-Roman Dark Ages).

A significant feature of the Fatimid era were the liberties afforded to thinkers and the emphasis given to mind, logic and reason, with people entitled to believe in whatever they wanted – contrast this to what was going on in Europe for centuries prior to the Enlightenment.

The famous ‘House of Wisdom’ in Baghdad is regarded to have included many Christian scholars and is believed to have been led by a Christian physician named Hunayn ibn Ishaq.

Various Islamic scholars of course also regard Muhammad’s position on Christianity as having been enshrined in his letter to the monks of St. Catherine’s – the oldest monastery in the world.

The “Achtiname of Muhammad” is a letter, held to have been dictated by the Prophet Muhammad, and addressed to a delegation from St. Catherine’s monastery (which, again, is an ancient Christian site that has stood uninterrupted in an Islamic nation for centuries). His message read: “This is a message from Muhammad ibn Abdullah, as a covenant to those who adopt Christianity, near and far, we are with them. Verily I, the servants, the helpers, and my followers defend them, because Christians are my citizens; and by Allah! I hold out against anything that displeases them. No compulsion is to be on them. Neither are their judges to be removed from their jobs nor their monks from their monasteries. No one is to destroy a house of their religion, to damage it, or to carry anything from it to the Muslims’ houses. Should anyone take any of these, he would spoil God’s covenant and disobey His Prophet. Verily, they are my allies and have my secure charter against all that they hate. No one is to force them to travel or to oblige them to fight. The Muslims are to fight for them. If a female Christian is married to a Muslim, it is not to take place without her approval. She is not to be prevented from visiting her church to pray. Their churches are to be respected. They are neither to be prevented from repairing them nor the sacredness of their covenants. No one of the nation (Muslims) is to disobey the covenant till the Last Day (end of the world).”

Salafists and radical, extreme Islamist preachers or propagandists have presumably found some way to bypass or omit those kinds of facts of Muslim/Christian history: but the point here isn’t to deny that there are people seeking to weaponise religion or religious differences for modern times, but simply to highlight it has no real basis in the religious traditions themselves.

Of course, plenty of people could counter that message by cherry picking verses from the Koran that apparently contradict it. It isn’t my business or interest to ‘defend’ anything in the Koran or from any religion (there are passages in both the Koran and Bible that I find difficult to deal with from a twenty-first century perspective): but most respected Islamic scholars simply argue that specific verses (relating to war, violence or ‘jihad’, for example) are to be understood within their historical context, primarily referring to events or situations contemporary to the time they were dictated in.

Which is why, having this understanding, ordinary Muslims in Europe aren’t out carrying out violent attacks, waging holy war, or interfering in anyone else’s right to live according to their own preferences – and that handfuls of radicalised individuals, indoctrinated into an extremist, non-nuanced interpretation of the religion, should never be the measure by which one judges an entire, diverse community.

The nature – and some would say the problem – with Islam and the Koran is that anyone can pretty much interpret any of it however they want.

And the problem within the Islamic world – especially going forward – is the question of who is going to win or dominate the battle of interpretation.

This is particularly dangerous in regard to the younger generations currently growing up in both an environment of toxic Islamophobia and division in the West and a situation in the East where sectarian, extremist groups and ideologies are flourishing in certain areas due to the conditions that have been created. If today’s Muslim teenagers and kids – such as the kids who carried out the horrific act in Normandy where a priest was murdered or the young men who go over to join ‘ISIS’ – have their world-view defined by ‘ISIS’ propaganda and Saudi/Wahhabi teachings on one hand and the growing Western anti-Islam propaganda on the other, then there is very little hope for the future.

If, however, Islam’s intellectuals, proper scholars, and its progressives and peacemakers, control the dialogue and the set the paradigm back to its proper form, then the crises can be diffused over time. What is clearly needed is more intelligent/intellectual Islam, such as what was traditionally to be found at the El-Azhar University in Cairo, and far less of the intolerant Salafist, Wahhabist nonsense that has been disseminated by its wealthy patrons for far too long now.

It will take combined efforts over time and a fight to curb extremism on all sides – including both the extremism within parts of Islam and the Far Right extremism rising in Europe – and it will take, most of all, a common desire to preserve or achieve a modern, secular, multi-cultural and non-sectarian society, but it is what needs to happen; because the alternatives aren’t worth thinking about.

In my own opinion, there’s no question that a secular society is always the answer and should be defended above the interests of any religious denomination or group; but one that respects and protects the rights of different religions and cultures, seeks or encourages harmonisation and belonging, has strong counter-radicalisation programmes and seeks not only to cut off or diminish the sources of extremism or sectarianism but actively seeks to empower bridge-builders, peace makers and inter-community dialogue, affording less prominent space to hate preachers and more space to voices of conciliation and integration, including, for example, the works of academics and experts like Karen Armsrong, author of Islam: A Short History and Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence, among numerous other books.

Pope Francis has also proven to be a leading figure in this regard; as much as I have issues with the papacy and the Roman Church in historic terms, I have to confess a fondness for this particular Pope and the way he has tried to lead the way as a bridge-builder (fittingly enough, as the original pre-Christian Roman meaning of Pope or Pontifex was literally ‘bridge builder’).

He also sought to lead the way for Western leaders last week by sending a letter of sympathy and solidarity to the Syrian people, but addressing it to President Bashar Assad as the recognised leader of that country – a gesture that a number of Western governments or officials would’ve disapproved of.

It might even be something of an irony that Syria might, depending on how things develop, manage to successfully preserve its own multi-cultural, secular society at a time when some European nations might find themselves willfully losing theirs in the coming years.

_____________

As for the idea of ‘Christmas’ itself being under threat, it simply isn’t true. If Christmas – in the traditional, Christian sense – is under threat from anything, it is from mass consumerism and commercialization.

It might not be shown on most Western news outlets, but in newly liberated Aleppo, Syria, this week, there was a big, public Christmas celebration.

In Lebanon, and in Palestinian Bethlehem, Christians and Muslims will celebrate Christmas together this year as they do every year.

Some – particularly those being drawn increasingly down the sectarian route – will think what’s being said here is naively optimistic or ignoring some of the serious issues that exist in some parts of society: but it really isn’t – it’s simply observing factual history.

Besides, sometimes we really do owe it to ourselves and to the future to be idealists and optimists and to seek the best scenarios for ourselves and each other rather than obsess about the worst. If I remember correctly, according to the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus also had good things to say about the peace makers too.

That being said, he might be a little baffled by Christmas itself, given that the season we’ve inherited as a celebration of his birth is actually a strange fusion of Christian ideas with Saturnalia and pre-existing Roman and pagan traditions – which rather neatly demonstrates that Christmas itself is a product of multi-culturalism in the literal sense. And that’s before you even factor in the fact that Christianity came to Europe from the Middle East in the first place.

Which makes the whole business of ‘them and us’ and ‘our tradition and their tradition’ seem all the more wrongheaded.

Beautifully said. I wish more people read your blog. I am a Syrian-American woman, and my mother is Muslim while my father is Christian. There has never been enmity between the two sides, not any more than a half-Catholic, half-Protestant family would feel! And yet, I have to explain this to my American friends repeatedly.

Thanks, FictionChick, I appreciate your contribution – especially as someone with an obvious understanding of what I’m trying to express.

Divisions of all kinds serves the masters of our world. Where none exists, they will foment one. We-humans fall into their quagmire every time.

In the New Year, may we re-discover the ties that bond us as humans of all colors, cultures, and belief systems.

Rosaliene Bacchus, Amen 🙂

‘Muslim values’ are easier to define as intended within a land, as they are specified for this purpose, a direct correlation and the desiring of Islamic society. It’s a religion designed for this and not really for places/peoples yet to arrive at this goal. As for Christian… says little more than, we’re better off with ever more and wider peace, and the church – an alternative within – community. Trying to make politics-christian, or a say a country thus, is generally a substitute for failing to better build the church. “If we can’t win them to us: try make everyone live like we want/believe should”. Not that we all can’t have our say/influence in line with beliefs/values, but claiming it’s a Biblical mandate is asking for co-opting corruption and… anyway, not found in the whole-of the Book. Most pronounced in evengelical-exodus-ing America, this divided up between a relatively strong socialist line (progressive evangelicals/liberals), and the more trad evangelical majority, who priorities a handful of concerns but most-often only see end-time decline and fall – therefore underlying “so/so what?” Where ‘Berlin’ is an attack upon (my understanding of) God, is the most-likely/almost certain, perpetration of lies. The anti-Christ’s religion. To have as many, and to as large an extent – have faith in bullshit and thereby mock ourselves unknowingly or, in going along-with for public/private ideological expediency/or fear. Worship the beast moves, toward the goal of more blatant and literal ‘bow-down’. And you rightly underline the other tenets of this wicked dark side; have them/us-all-a-fighting. Blame the Is. violent relatively-few and certain authoritarian clergy-led-Govt’s and lackeys, on the belief that multitudes see as up-for, let’s get along with ‘others’. As for; ‘All of this propaganda perception of a Muslim/Christian divide is entirely… …previously weren’t allowed to have much influence.’ Adjusting for historical context – one big Yup to this. And more yep and the exposure of more enemy tactics: “Make those we oppose extreme to justify fighting”. Not so sure about; ‘The export of Islamist terrorism to Europe’. Get the ‘other hands’ involved caveat although yet to be convinced, contemporary acts of terror aren’t theatre? Terrorising the gen. public nevertheless.

Much in the rest of your informative and sober article, but won’t exceed on. One thought: The need to project-on to. Make Islam/Koran the simple roots of said-destruction and oppression. There’s some truth to ‘as written’ but only ‘some’ and the myriad of merging influences are too nuanced for those sickeningly on headline ramping, sarcastic hate. Especially galling, when links between false-flags (where’s the evidence/makes sense, otherwise?) -and- complete psy-opp-ing fakery (where’s the evidence/clearly demonstrates couldn’t be?) – and Allah inspired, are found pitifully wanting. And somewhat purposely, not covered-up enough, to show the intention is part deep state/cult unveiling aka ‘apocalypse’ and along the way allegiance we-to-must confess our faith. End on some sermonising: to quote J. Strummer, ‘the future is unwritten’ and so saith the God of the Bible. At least, in there’s much room for maneuver and freedom for freedom, to be won/held/won and on. AND: The claimed purpose of why Jesus etc etc – is that we may ‘know’ God and this one all encompassing up for us and loves.

Epic stuff, Mark – as per usual. And I didn’t imagine this post could possibly elicit a Joe Strummer quote, so good work, bro 🙂

Last night at the end of the BBC’s Who do you think you are, Ricky Tomlinson made the following statement which kinda fits in with your sermon…”practice a religion if you want to but don’t use it as a weapon against anyone else”. Being of no religion myself this simple sentence sums it up for me. From my perspective religion is about power and control of the masses. Each time a new sect comes out of one religion or another it has been about taking power and control away from the original group and that divides us. While I agree with you that we need more acceptance of each others religious beliefs (including those with no belief) we also need to learn to stop giving the leaders of our religions power and control over us.

Is Ricky Tomlinson the Royle Family guy? I think I met him once – nice bloke. Yeah, I agree with his quote too. I agree with you to a point about power and control of the masses; but I think that’s at the point where a belief system becomes institutionalised and therefore ‘administered’. I think I have a lot more respect for religion at the root/origin levels *before* the ideas get taken into the power/control level.

It’s very tricky though, admittedly.

Reblogged this on Lolathecur's Blog Below are two very important entries from the "Jewish Encyclopedia". Read them VERY CLOSELY..