You don’t have to be Christian or even religious to appreciate the compelling and magical properties of the Nativity story, with its evocative and timeless images and the ideas it evokes.

The imagery and mythology of the Nativity narrative – Magi, star, Herod and all – is something I’ve explored and navigated here before, in an older Christmas time piece. This time we’re focused more on the historic setting of the Nativity – and its modern day counterpart: Bethlehem.

And especially how the Bethlehem of today actually has curious parallels and resonance with the Bethlehem and broader Judea of the Gospel period. Many centuries and a great deal of history may separate that time period from today: but it is remarkable how much appears to have circled back on itself.

Modern Bethlehem of course resides on the fault-line of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, its urban sprawl part of the West Bank. When most tourists or ‘pilgrims’ approach from Jerusalem, the “Little town of Bethlehem” is in fact their first taste of Occupied Palestine. Some cinematic depictions of the Nativity story over the years have had Mary and Joseph having to negotiate Roman checkpoints during their journey: today the checkpoints are Israeli.

Two thousand years or so after an anomalous star or star-like object – or so the story goes – rested over the town, having apparently guided three wandering Magi, something occurred last Christmas that harboured a strange resonance with the Nativity narrative.

Specifically, the extraordinarily rare conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn that took place in December 2020, a few days before Christmas.

The resonance is because the theory has grown in popularity for some years now that the mythical Star of Bethlehem might’ve actually been a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, creating an extraordinarily bright object in the sky. This theory in fact goes as far back as the 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler, who suggested a similar conjunction had occurred in 7 BCE (three years before the death of Herod) – and might’ve been the origin of the Star of the Bethlehem story.

Articles last December were unabashedly referring to the 2020 conjunction as ‘the Christmas Star’: a cosmic event not expected to occur again until 2080.

Aside from being a fascinating spectacle in itself (look at the video footage above, uploaded to YouTube), it also prompted me to wonder what would happen if the 2,000 year-old Nativity narrative was transposed to the modern day.

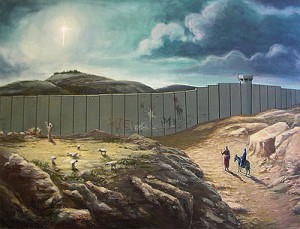

Well, the first thing you can’t help but realise is that any prospective ‘holy family’ trying to make that journey today wouldn’t actually *reach* Bethlehem, given the enormous wall that has been erected (aptly satirised in the image below, whose source I’ve sadly been unable to definitively identify, though it is commonly attributed to Banksy).

Even before reaching the wall, they’d have to get through the various checkpoints.

Something like 90,000 people reside in the broader Bethlehem area, with three refugee camps having come to embody the struggle of the Palestinian people that has now been going on for something like 70 years. The continuing occupation places Bethlehem’s residents under severe economic and social pressure.

The ‘Separation Wall’ runs around the northern edge of the city, over two miles inside Palestinian territory, inhibiting the movements and possibilities for residents.

It wouldn’t take much in the way of imaginative faculties to look at the situation of Palestinians today and to think of the oppression of Jews under the Romans during events of the Gospel narrative.

History is of course replete with ironies and recurring motifs. You could look at the more extreme elements of modern day Palestinian ‘terrorism’, for example, and see the parallel to Gospel-era Jewish Zealots or Sicarii and their violent campaigns against the Romans.

Different time periods – but very similar dynamics.

Whatever Bethlehem may or may not have been like two thousand years ago, today it is characterized by military checkpoints and the extraordinarily oppressive security barrier that separates Bethlehem from Jerusalem, along with the shuttered homes and boarded up shops that are symbols of the stagnating economy and the illegal Israeli settlements that are still appearing around Bethlehem.

82% of Bethlehem apparently falls inside ‘Area C’, which is territory under direct Israeli military and administrative control.

Modern Christian pilgrims sometimes report their surprise at the essentially Arab sense of the town, being different from the somewhat idealised image or idea of Bethlehem that has imprinted itself on Westerners’ minds since childhood via all the age-old religious iconography.

In all likelihood Gospel-era Bethlehem probably had that same flavour to it and was nothing like the picture-book fairytale image to be found on Christmas cards.

The Muslim and Christian Palestinian community has lived and worshiped alongside each other for centuries, with the Church of the Nativity itself hallowed and preserved for Christian use over the years. Tolerance and a sense of communal brotherhood has traditionally been a defining feature of Arab Bethlehem, with the town’s Muslims often to be found praying inside the Church of the Nativity.

It is a Sunni Muslim family that looks after the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, one of the holiest sites in the Christian world. And, as explored previously, it is the Sunni Hashemite King of Jordan who has legal custodianship over both the Christian and Muslim sites in the Holy Land and is charged with their protection.

The ‘No taxation without representation’ campaign initiated in Beit Sahour in 1989 helped spark the Palestinian campaigns of civil disobedience that marked the early stages of the First Intifada, lasting around six years. Halfway through the Second Intifada, dozens of Palestinian fighters sought sanctuary in the Church of the Nativity itself; the Israeli siege lasted almost five weeks, with around 200 Christian monks trapped inside the church.

At the conclusion, the church’s bell-ringer was killed along with nine Palestinian fighters.

Bethlehem remains at the forefront of the Palestinian national movement and identity; an identity that has for the most part been just as Christian as it is Muslim: the Palestinian cause has traditionally been regarded as a secular one by those living it (although this pluralistic and secular identity has been severely compromised in recent years: much of it by design).

In more recent times, particularly with the violent spread of extreme Islamism in both Palestine (the rise of Hamas – parallel to the rise of Israeli extremism) and in the broader Middle East, there has been a reported exodus of traditional Christians from both Palestinian towns and other parts of the region: though it isn’t clear how large this exodus has been.

A particularly interesting Washington Post piece from a few Christmases ago reported on Vera Baboun, Bethlehem’s first female mayor, who wanted to make the city open to all again, especially to Christian pilgrims and to those Palestinians who had fled. A Christian whose late husband had spent three years in an Israeli prison during the first Intifada, Baboun was calling for Bethlehem’s former community to return home, hoping to restore some of Bethlehem’s previous make-up and spirit.

The state of Bethlehem today is one symptom of the breakdown in inter-faith relations and social harmony that has been characterising the Middle East in recent years due to various divisive and polarising factors: again, some of it by design – witness Israel’s role in supporting the rise of Hamas, for example, or the role of various foreign powers (Iran, the Saudi and Gulf States, the UK and the US included) in igniting and manipulating sectarian strife in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere in the region.

Culturally and sociologically speaking, the 21st century has seen things going backward rather than forward.

Not that 1st century Bethlehem was likely to have been idyllic either; according to the story, Mary and Joseph had to knock on a fair few doors before finding anywhere to settle down and even then the best they were offered was allegedly a stable – the spirit of human kindness clearly wasn’t in broad currency even for a pregnant woman, according to the gospel authors.

Given today’s toxic and widespread anti-refugee, anti-migrant sentiment around the world, I’m not sure a modern day Mary and Joseph would necessarily find much sympathy. Then again, in Bethlehem they just might.

The climate and environment that the Jesus of the Gospels emerged into was one of religious and political strife, extremism, military occupation and terrorism: it really isn’t too different now.

And life under Herod on the one hand and the Romans on the other was clearly no picnic for the Jews then, just like it isn’t for Palestinians today. Even many of the more modernised, Hellenistic Jews of that period were also caught in the crossfire between their more extremist Jewish counterparts and both the Romans and Herodians on one hand and the Jewish priesthood on the other.

It always strikes me as odd that more Jewish commentators of the modern day don’t see or point out the obvious similarities between 1st century Jewish rebels or resistance fighters and modern Palestinian resistance (the Jewish Zealots included suicide agents, just as the modern suicide bombers have become such a trope).

Perhaps it’s an uncomfortable subject: after all, those 1st century resisters of occupation – and in particular their apocalyptic last stand at Masada (ending in mass suicide) – are seen as a heroic symbol for modern Israel.

Drawing any comparison with current day Palestinian resistance would obviously cause problems in the national narrative and might create a tricky cognitive dissonance. That being said, I’m not sure Palestinian terrorists would particularly like being compared to ancient Jewish fighters either.

Obviously, it’s a highly sensitive issue. For one thing, that very cycle of violence and resistance by the Jewish Zealots is ultimately what led to the destruction of the Jewish Temple in AD70 and the end of the Jewish homeland for nearly two millennia. In historical terms, the Jewish people have only just returned to Palestine after two thousand years in diaspora: Israel is still a relatively new nation.

Maybe it’ll take another generation or so for these kinds of observations or reflections to gain any currency. Or maybe they never will.

But again, the point is that Bethlehem and Palestine today really aren’t too different to two millennia ago. Jesus and his contemporaries in 1st century Judea would probably recognise a lot of the dynamics and issues of the region today and understand them very well.

Though the part they would possibly find strangest – or most ironic – is that the role of the Jewish State in this transposed narrative would inevitably have to be likened to that of the Romans in the original narrative: with the Palestinian resistance movements inevitably being analogous to the Jewish Zealots and various anti-Roman factions of 1st century Judea.

Quite what they – or any 1st century Jew in Palestine – would make of that is anyone’s guess.

Jerusalem, Trump, the Christian Zionist Crusade & the Biblical Apocalypse…

It started busy but has dropped off quite a bit! That part of it was especially fun I must say. Would be great to talk about the universe and related issues (although I guess “the universe” pretty much covers everything really!)

Here’s a link to the article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hughes_(astronomer)

The photo is top right (and there’s another at the bottom). You’ll also see reference to his book “The Star of Bethlehem: an astronomer’s confirmation”. And here’s a link to a clip of David Hughes on Sky at Night talking about the theory: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgQDPKoydxs

That’s fantastic, thanks for sharing. I’ve always liked the theory, but had never come to David Hughes specifically. As for you yourself, you’ve had a busy life, it seems like 🙂 Would love to discuss the universe with you some day.

History doesn’t repeat but it rhymes. (Mark Twain I think.) Btw, the conjunction theory of the Star of Bethlehem was popularised by the astronomer Dr David Hughes. There’s a short wikipedia article about David Hughes (who also has an asteroid named after him) including photos of his research group back in the early 90s. I’m the young guy in that ear-piercingly loud jumper!

You’re right – it rhymes rather than repeats: I didn’t think about that sentence long enough. I’d like to see that photograph with the loud jumper. Thanks for commenting.