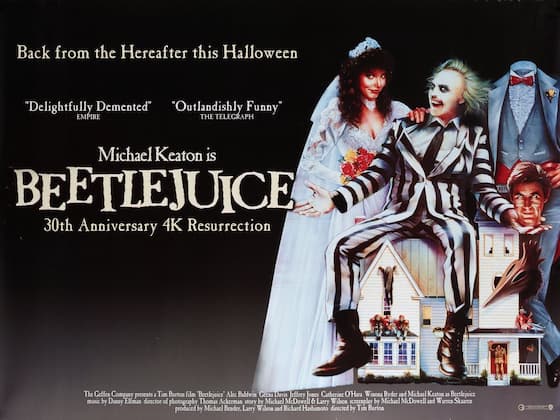

35 years after the original film, the sequel to the cult classic Beetlejuice has just hit cinemas.

And it appears to be both doing good business at the box office and receiving mostly positive reviews.

Which I’m glad about, I think: it’s refreshing for one of these nostalgia sequels to actually be well received, instead of provoking backlash or criticism.

From reviews I’ve read (and I haven’t seen the film yet), this might be partly because Beetlejuice Beetlejuice manages to retain both the weirdness and the visual uniqueness of the original without feeling entirely like a cynical rehash or cash-grab.

I mean, it is a cash grab, really: it would never have been green-lit if it didn’t have that nostalgia-bait potential for turning a profit.

We’re in the era of nostalgia product and trying to recreate the past.

And while much of this results in ill-conceived or bloated and badly executed projects like Disney’s train-wreck Star Wars sequels, the recent Indiana Jones movie that everyone’s already forgotten, or the shoddy Ghostbusters reboots, it isn’t necessarily automatic that a nostalgia-based project has to be bad.

That being said, the upcoming Gladiator sequel is going to be bad: it has to stand as one of the most unnecessary films of all time.

But Beetlejuice Beetlejuice appears to be bucking the trend.

It might help that this decades-later sequel was in the hands of the original’s creator and not some new committee or corporate think-tank. And Tim Burton probably has enough fondness for his old cinematic oddity that he wouldn’t commit to a sequel unless he had a good vision for it.

He hasn’t tended to revisit or try to revive old works: otherwise a sequel to the animated masterpiece Nightmare Before Christmas would’ve been a no-brainer for a commercially profitable enterprise at any point in the last two decades.

Given Burton’s creative decline in the last fifteen years or so – taken up by stale blockbuster franchise productions and lifeless Disney projects – he probably welcomed going back to one of his earlier worlds, back when he was a visionary filmmaker with a unique style

And not simply a safe pair of hands for major studios and the blockbuster machinery.

I was a fan of the original Beetlejuice film. As a little kid in the late eighties, I watched that VHS tape over and over again.

As an adult rewatching that Gothic slice of weirdness and offbeat comedy, I can appreciate it even more: except now I’m not so much laughing at the gags or going wide-eyed at Michael Keaton’s off-the-wall shtick, but noticing the stunning use of colour and of light and dark, or the surrealist effects of the stop-motion animations, and in general the addictive visual style that permeates Burton’s early films.

I’ll always have a fondness for the offbeat surrealism of those late eighties and early nineties Burton productions: and Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, The Nightmare Before Christmas, and the Keaton-era Batman movies remain some of my favourite films.

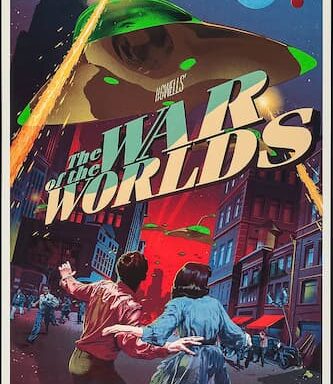

There was something also about that era in cinema – the eighties primarily – that seemed to encourage or allow wacky ideas and highly creative concepts to get studio support: and therefore for very creative filmmakers to flourish.

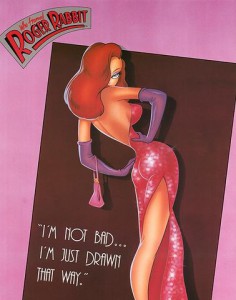

Burton’s films, as well as films like the original Ghostbusters, a landmark live-action/animation hybrid like Who Framed Roger Rabbit, or an entirely puppet-based fantasy like The Dark Crystal, are some obvious examples.

Little Shop of Horrors is another.

And these types of movies had an edge to them: they weren’t sanitised or overly child-friendly fare like you might think.

Roger Rabbit, for example, has some genuinely unsettling moments and is in some ways a very grown-up movie in tone. And let’s not pretend Jessica Rabbit wasn’t one of the most sexually suggestive movie characters ever.

The Dark Crystal, despite being a kid’s film, actually has dark and upsetting themes.

And there’s fairly adult humour in most of these films, including things like Beetlejuice and Batman Returns.

Some of the horror elements in Beetlejuice, despite being comedic, are still pretty grotesque: and looking back as a grown-up, probably not all that suitable for kids.

Geena Davis’s rotting corpse face comes to mind as an example.

But that allowance for edginess to some of these films, and genuine weirdness in tone, is part of why they tend to hold up so well.

I’m even going to go out on a limb here and say that I still prefer David Lynch’s Dune film to the modern Dune franchise.

As deeply flawed and imperfect as that eighties Dune is, what it has is that absorbing quality of weirdness and surrealism: even seeming sometimes to revel in its messiness and unperfected nature.

The modern versions feel highly streamlined and sanitised by comparison: making for much better and more cosmetically immaculate blockbuster fare, but less entertaining and less absorbing.

That said, David Lynch doesn’t even defend his Dune film: so maybe I should get off that subject.

But chances were being taken with big-budget undertakings, maverick creatives and original visions. These days, everything feels far more streamlined and far more about playing it safe and formulaic for maximum profit and minimal creative risk.

The very existence of this Beetlejuice sequel is, somewhat paradoxically, proof of that: as Burton and the studio would rather revisit an old classic with a preexisting fanbase rather than Burton looking to create something new.

One of the other discernible things about some of those eighties movies is that they tended to defy easy categorisation: and this seems very significant.

Is Beetlejuice a kids film? Not really. But kids watched it. Is it horror? Comedy?

Was Gremlins a kids film? Again, not really: but it was mostly kids watching it.

What was Ghostbusters primarily? Comedy? Sci-fi fantasy? Horror?

A lot of these movies didn’t have an obvious pigeonhole. In today’s cinema environment, you sense studios and committees wouldn’t even green-light a movie unless they were absolutely clear about target audience demographics – and most crucially, how to market the film.

In the eighties, it didn’t seem to matter that much. It seems to be that it was more like, ‘Here’s the movie, here’s the poster, here’s the trailer – make of it what you will’.

Which seems like a more exciting creative environment for a filmmaker: perhaps richer with possibilities, and more margin for error.

Anyhow, these are some of the reasons I think films from that era seem to endure so well: Beetlejuice included.

And, as much as this sequel endeavour seems like simply more nostalgia-driven content typical of this current era, it at least seems to have a different vibe around it.

Unlike something like the bafflingly dull and pointless Indiana Jones & the Dial of Destiny from last year, this at least feels like a passion project with some enthusiasm behind it.

And just existing for a bit in that strange little world with its unique visual language and oddly comforting sort of surrealism might be a welcome distraction.

If the reviews are anything to go by, this might be one of the few instances where a nostalgia-driven movie project might actually hit the mark.