The various Holocaust memorial events across Europe that marked the 70th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation received a great deal of (justified) coverage on news channels and in papers in recent days.

There have been entire libraries of art, film and literature inspired by the horror and suffering of the Holocaust of course.

I made the point a few days ago that this abundance of Holocaust-related material can sometimes have the side-effect of making people feel ‘over-fed’ on the subject, to the extent that it sometimes somewhat lessens the impact of the Holocaust’s reality. Which is why events like the Holocaust memorials of this week are hugely important in reminding people, even someone like me who considers himself fairly well-versed on the subject.

And sometimes new, inventive ways to express something about what happened in Nazi Europe provide a very effective means of re-connecting with the reality of the subject on a subjective level; a level that bypasses facts, figures and dates, and bypasses language (written or spoken) entirely, connecting instead with the purer sense level of perception.

A very good example of this was provided by the Dutch theater company Hotel Modern and their work Kamp from 2010; to start with, it was a 36-by-33-foot model of Auschwitz populated by 3,000 three-inch-tall figures. Pauline Kalker, the founder of the Dutch company, is herself the child of a Holocaust survivor. The compelling installation, made primarily of plain gray corrugated cardboard, included the guard towers, barracks, crematoriums, gas chambers with buckets of gas pellets, a dining hall for the guards, a train and tracks, and of course the infamous words that greeted Auschwitz inmates as they arrived at the camps; ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ (“Work Makes You Free”).

‘Kamp’ combined music, theatre, sculpture, puppetry and video to convey its highly inventive, novel, highly stylised, absorbing and ultimately very moving expression of Auschwitz.

The spirit of’ Kamp could be said to have followed somewhat in the footsteps of the acclaimed 1986 graphic novel, Maus, by Art Spiegelman, which portrayed Jews as mice and the Nazis as cats, opening the door for Holocaust stories to be conveyed in styles or genres that for a long time would’ve been seen as too irreverent and perhaps disrespectful.

Something like Kamp isn’t to everyone’s tastes, of course; but it was a remarkable work of art and expression that was aimed at the senses and not the intellect.

It is, the argument can be made, in the unfiltered senses that the strongest impressions and perceptions occur, without the intellect attempting to rationalise the information.

I watched a couple of programmes on the BBC this week focused on Holocaust survivors and their lives after being liberated; the programmes were naturally very moving, enabling even someone like me who’s read a lot of books on the Nazis and the Holocaust and watched countless documentaries on the subject, to reconnect anew with the same original feelings and reactions I had when I first saw Auschwitz footage on TV as a child – images that always remained in my mind.

Those grainy black-and-white images of the concentration camp prisoners staring with haunted eyes from behind barb-wire fences made so much of an impression on my mind as a child in fact that I can readily bring them to mind at any time and they are a more prominent fixture of my psyche than any of the detailed passages or facts in whatever books I’ve read on the subject.

Which goes back to the point about something like the Kamp installation and the power of sensory information.

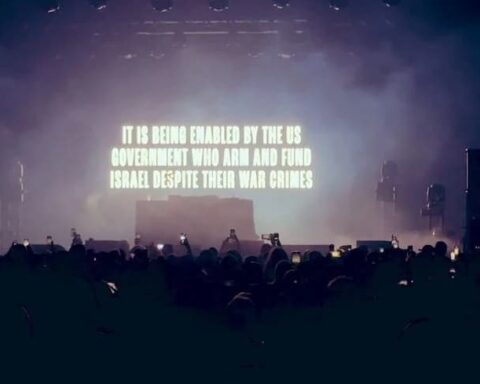

As all historians note, the Holocaust occurred in a supposedly enlightened, modern, educated country and not in some far-off wilderness cut-off from modern life. With enough deep-seated and widespread hatred of a religious or racial minority and a state that has been taken over by extreme right-wing politics, something similar could conceivably happen some time in the future; what happened in Kosovo and Bosnia was less than twenty years ago, bear in mind.

Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress, told a recent gathering of leaders, including France’s President Hollande, that Europe today “looks more like 1933 than 2015”; a troubling, if understandable, observation.

Another survivor of the Nazi horrors, Henry Wuga, told BBC Good Morning Scotland: “A government made a decision to eradicate a whole people. It is absolutely mind boggling and it should not happen again.”