Augustus is without doubt one of the most fascinating figures of history; and also one of the ancient historical figures we know most about because he left such clear marks on the world: politically, religiously, even physically.

He wanted everyone to know who he was, when he lived and what he did.

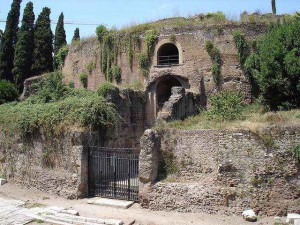

I started writing this article originally to mark the 2,000th anniversary of his death, which was in 2014: but I was waiting for Rome to restore and reopen the derelict Mausoleum of Augustus before posting it. That was the plan that had been announced by authorities in Rome at the time; but the highly anticipated restoration and re-opening of the Mausoleum never materialised, due to lack of funds.

2016 was then given as a date in which the project would finally see fruition; but so far there have been no announcements of progress – a subject I already covered here.

So, having waited a long time, I belatedly post this article up now: in commemoration of one of the greatest figures of history, a man still being written and argued about 2000 years after he shook off his mortal coil.

Augustus has of course always been a fascinating figure.

He lived, however, in a time that produced a number of equally fascinating figures: Caesar, Antony, Cicero, Brutus, Claudius and Caligula, to name just a few. And it is perhaps because of the time and environment he lived in and because of his life and story in relation to those other contemporaries’ stories that Augustus retains such an eternal hold on our imagination.

It also helps, of course, that so much historical record, written text and archaeological record exists in order for us – so far removed from his world – to retain a sense of connection.

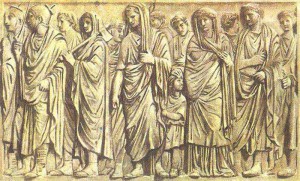

More statues and busts of Augustus have survived than of any other emperor. His ‘official’ face remained, throughout his reign, one of eternal youth and vigor — a perfect illustration of Augustus’ careful management of his own image, which we can see echoed in dictators right through to our modern age.

Temples and monuments in his honour or built in his name can still be found in multiple countries, while statues or busts of him, along with coins bearing his image, are unearthed as far as Africa and the Middle East. Remains of striking busts of Augustus have been found as far afield as Sudan and Tunisia.

It is possible that no figure from distant history was able to leave such a far flung mark on the world and for so long.

Here was a figure who is credited with (or blamed for) having overseen the end of the Roman Republic, while being regarded the founder of the Roman Empire; yet also a figure credited with having brought peace and an era of stability and growth to a chaotic, warring civilisation. He was also, prior to his adoption of the title ‘Augustus’, also able to claim the title of ‘Son of God’ on account of the Senate posthumously recognising his adoptive father (real-life uncle) Julius Caesar as a divinity of the Roman state.

Caesar was a ‘god’ and so Octavian was a ‘Son of God’. Within his own lifetime, he was regarded as divine; beyond his lifetime, his deification was never in doubt.

Adding to this Messianic aura around Augustus, Suetonius describes omens and dreams that predicted the birth of Augustus. One suggested that his mother, Atia (portrayed unforgettably by actress Polly Walker in HBO’s ROME), was a virgin impregnated by a Roman God: an idea that would later be echoed in other Messianic figures’ traditions.

Aside from memorials and ruins in Rome and Italy, across Europe and even into the Middle East, Augustus’ name and ghost remain a permanent presence or echo in our modern lives and cultures. Both his title ‘Augustus’ and his adoptive surname ‘Caesar’ were adopted as permanent titles for rulers of the empire for centuries beyond his death. Beyond Rome itself, ‘Caesar’ became the word for emperor, translated in Germany as ‘Kaiser‘ and in Russia as ‘Tsar‘, so that even rulers and powers as little as a century ago during the First World War were bearing Caesar’s name.

We still pay tribute to him in the eighth month of every year, named for him, and we still use the term ‘Augustan Age’ to refer to any golden era of any society or civilisation. His early title ‘Pontifex Maximus’, which made him Rome’s most senior religious authority — was a title later adopted by the popes in Catholic Rome.

And we can also wonder how many leaders, nation builders or dictators all the way through to the present day have modeled their reigns – knowingly or otherwise – on what Augustus did 2,000 years ago. Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, for one, has always struck me as a leader bearing much in common with Augustus.

It is tempting to attempt to wax lyrical here about Augustus’ life and accomplishments and try to carve out a lengthy recounting of his life and character: but his life, actions and character have already been so comprehensively analysed and interpreted and re-interpreted over the centuries that it becomes a needless task, as well as a herculean one given the sheer volume of information and considerations that the record of Augustus’s life gives us.

The Roman writers and historians themselves analysed Augustus to death, with their differing perspectives, while the analysis has continued for centuries to the modern day, with books and essays still trying to assess and re-frame Augustus’s extraordinary life and the extraordinary times in which he lived.

Ruling from 27 BC to his death in 14 AD, Rome’s first emperor was the founder of the dominant imperial dynasty that laid the foundations of Western civilisation and was the cementer of Roman domination. Augustus’s reign laid the foundations of an empire that prevailed for centuries. Some would say not just up to the decline of the Western Roman Empire, but for some 1500 years up to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

But the story of how Augustus rose to power in the first place is just as compelling as what he did once he attained it.

Spurred on by the murder of his uncle Julius Caesar, Augustus – then called Octavian – had launched himself into the tumultuous civil wars and power struggles raging in Rome in order to attain essentially the power for himself that his uncle had had violently taken away from him. One by one, he found the means and the fortune to defeat the legions of the other contenders who sought to succeed Caesar as master of the Roman world.

He should’ve in fact been the underdog, particularly when pitted against the Republican forces of Brutus and Cassius who had the aristocracy and the weight of name and tradition behind them, and the sheer military prowess and weight of the people’s hero Mark Antony.

Yet Octavian (depicted above in Egyptian style at the Temple of Kalabsha), who was no military genius himself, was the ultimate victor: he was the last man standing as the Republic crumbled around him.

After defeating Antony and Cleopatra at the legendary Battle of Actium, Augustus established the ‘Pax Romana’ (The Roman Peace) throughout the empire. After years and years of wars and violence, Augustus presented himself as the bringer and ensurer of peace.

Yet Augustus is a figure of contradictions. He was absolutely committed to a return to traditional values and ideals and spoke of restoring Rome to what it had once been in the past: yet at the same time he was a revolutionary in everything but name, who transformed the nature of Roman politics and government forever.

He paid lip service to the virtues and integrity of the republic, yet subverted that republic entirely.

While assessments of Augustus’s reign differed over time, with some later Roman writers highly critical of him, the Augustan era poets Virgil and Horace praised Augustus as a great defender of Rome, a guardian and promoter of moral justice, and as the man who took it upon himself to preserve the integrity and stability of the empire. To others, particularly later on, he was a tyrant who had doomed Rome to endless dictatorship.

But Augustus’ rule was about more than government, military or political dynamics: he sought to be a shaper of society itself, of hearts and minds, morals and culture. Aside from building and restoration, he was also a great patron of the arts, of literature, poetry, and learning. A builder of roads and temples, a spreader of civilisation, Augustus also heavily rebuilt Rome itself, establishing it as the capital of culture, and setting up the city’s first police and fire-fighting services. Among the monuments built under Augustus’s watch were the Temple of Caesar, the Baths of Agrippa, and the Forum of Augustus; but building and tribute extended well beyond Italy and all across the Roman world.

Much of the world remained a tribute to Augustus for centuries beyond his lifetime: carved in stone or marble or bronze, written on tablets or struck on coins.

This is part of the context for his famous last words being “I found a Rome of bricks; I leave to you one of marble”. However, his alternate last words were reported to have been the more pleasing “Have I played the part well? Then applaud as I exit”.

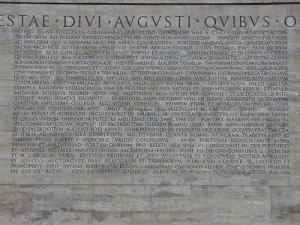

His foreign policy was layered, favoring a great deal of diplomacy and bridge building. The third section (paragraphs 25–33) of the famous Res Gestae (‘The Deeds of the Divine Augustus’, which was issued on his death and reproduced all over the empire) describes his military deeds and how he established alliances with other nations during his reign.

Beyond the existing frontiers, he secured and expanded the empire and created a region of client states, as well as establishing peace with Rome’s bitter rivals the Parthian Empire through diplomacy. He also established the Praetorian Guard and transformed the nature and dynamics of power and government in Rome; for better or worse.

After the demise of the Second Triumvirate (consisting of himself, Antony and Lepidus), Augustus restored the outward facade of the free Republic, with governmental power resting in the Roman Senate, the executive magistrates and legislative assemblies. In reality, however, he built up his own autocratic power over the Republic as a military dictator in all but name: a modus operandi that would copied or echoed by numerous dictators over the centuries.

By law, Augustus acquired a collection of powers granted to him for life by the Senate, including supreme military command and the powers of tribune and censor. And over several years, Augustus cleverly developed the framework within which a republican state on its surface could nevertheless be governed under his sole rule. In effect, he had accomplished for himself what his uncle Julius Caesar had once sought, but he had also somewhat learnt from some his uncle’s mistakes and made sure that his position and powers were framed within terms that allowed for the illusion of a free republic.

In essence, he subverted the Republic via a mixture of soft and hard means and incrementally.

Roman historians, and even modern historians, differ in their ultimate view of Augustus, some regarding him as a tyrant who was responsible for the end of the Roman Republic, others as a great stabiliser and nation builder and a man of moral virtue.

The consensus reality probably has him as both. He was obviously ruthless and ambitious and autocratic; but he also appears to have been a sincere idealist, genuinely seeking the best interests of the state and the society, which itself may have coalesced logically with his own personal power or ambition for a long time. What we, with our modern sensibilities, tend to regard as the negative or tyrannical traits, can of course co-exist within the same person with what we might regard the positive, noble traits, with both guiding his actions and, together, defining his nature.

There were and would later be plenty of equally ruthless dictators in Rome, but who would be driven primarily by their own thirsts for power and prestige: no one would suggest that Augustus was as one-dimensional as that. His ideals and vision appear to have been sincere.

Octavian is often portrayed as being ruthless and merciless towards enemies; yet he was also given much credit after Actium for pardoning many of his opponents.

We can see his ruthlessness in, for example, having Cleopatra’s young son Ceasarion killed; yet at the same time he spared the lives of Cleopatra’s other children by Antony. He couldn’t let Caesarion live because he was a son of Julius Caesar and therefore a direct threat to Augustus’s position; but he had no strategic reason to kill Antony and Cleopatra’s other offspring, so he didn’t. Some of the later emperors wouldn’t have exercised such mercy or restraint.

One of the most ruthless acts he was involved in was near the end of the Second Civil War, in which he – then under the name Octavian – was in an uneasy alliance with Mark Antony in a war against the heroic Republicans Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus.

The triumvirate of Octavian, Antony and Lepidus set in motion proscriptions in which much of the Roman aristocracy and senatorial class, including 300 senators (the figure given by Appian; though Livy suggests only 130), were branded as enemies of the state, having all of their wealth and property seized and many of them being executed. High rewards for action taken against the proscribed names offered incentive for some Romans, including criminals, to carry out the purge. The assets and properties of those in question were seized by the three triumvirs.

It has been a debated question as to which of the three was most responsible for the brutal purge.

Marcus Velleius Paterculus seemed to suggest Augustus tried to avoid the proscriptions and was goaded by Antony and Lepidus. Cassius Dio also suggests Augustus tried to spare as many of the officials as possible. But it is mostly agreed that this action was a means for all three of them to tidily eliminate all their personal enemies. Appian doesn’t share Paterculus’s sympathetic view of Augustus’s role, maintaining that Octavian shared an equal interest with Lepidus and Antony in eradicating his enemies, while Suetonius forwards the case that Octavian, although reluctant at first, actually pursued his enemies with more rigor than the other triumvirs.

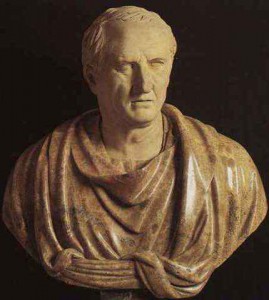

Interestingly, in the superb HBO/BBC historical drama series ROME, Lepidus is depicted as the most reluctant, with Antony depicted with a kind of casual ruthlessness and Augustus (Octavian) shown as being more logical and calculated (and to some extent, goaded on by his mother). It depicts Octavian, in any case, as being fully committed to the proscriptions. Among those purged included the great orator and statesman Marcus Cicero (depicted in bust above).

One of my favorite anecdotes concerning the older Augustus was that, according to Plutarch, he in later life would praise and extol the virtues of Cicero when in private conversation.

The proscriptions that had led to the murder of Cicero and numerous others might be seen as a strategic necessity or as excessive and corrupt killings, depending on who you talk to. There is also a case to be made that his ruthlessness was necessary in a ruthless time and in order to be able to try to implement his vision for Rome and for Rome’s place in the world.

____________________

While some argue he is ultimately a dictator and autocrat, there is the counter-argument that, firstly, he did what he had to not only to acquire his own power and status but to bring peace and stability to Rome after years and years of civil war and power struggles, and secondly, that he simply could not later give up his authority without risking a return to civil wars in Rome and power struggles between ambitious generals or aristocrats.

We can see this, for example, in the bloody ‘Year of Four Emperors’ that followed the death of Nero, the final emperor in Augustus’s Julio-Claudian dynasty: in that year, the imperial leadership changed hands three times in a bloody, violent game of thrones between rival claimants and their armies.

An argument is made that even if he had desired no position of authority whatsoever, both his position and his outlook demanded that he look to the well-being of the city of Rome and the Roman provinces. And while it is certainly true that Octavian/Augustus presided over the decisive fall of the Roman Republic and its transformation to empire, it is also the case to be argued that the Roman world would never have stabilised and prevailed for as long as it did if Augustus hadn’t followed the course he followed.

It is one of the fascinating questions of history to wonder what would’ve happened if Brutus and the Republicans had won the Battle of Philippi and Octavian and Antony had been defeated.

Would the Republic have prevailed in the long term? Could Republican Rome have established its own ‘Pax Romana’ and ended the power struggles, bringing stability? Or did destiny really need Octavian himself to live to do those things? Or, regardless of Philippi, would there have been eventually been an Imperial Rome anyway: was this simply an organic, inevitable destination?

It is difficult to re-imagine Imperial Rome without Augustus (immortalised in kameo in the picture below) as its architect or the end of Republican Rome without Octavian as the last man standing.

But Augustus, like anyone else, wasn’t just a phenomenon in a vacuum, but the product of his life and times.

He had grown up witnessing and experiencing the instabilities and bloody consequences of a corrupt, failing Republic. He had watched rival, feuding parties and interests tear Rome apart. And he had watched his uncle and probable role model Julius Caesar be brutally murdered in the Senate.

All of this had no doubt imbued him with a sense of righteous destiny: believing he had both the intelligence, vision and education to rescue Rome and be a ‘saviour’ of the Republic, who would step in and bring peace and order. A savior is precisely what he later presented himself as and what many Romans received him as.

The fact that the ‘saviour of the Republic’ would in fact abolish the Republic and establish an Imperial Dynasty was either a genius sleight of hand or simply one of the great ironies and contradictions.

It is, however, questionable whether Augustus was simply power hungry or whether he perceived that autocracy was the only way to shepherd Rome away from a tumultuous era. In establishing what would become the Julio-Claudian Dynasty, he was arguably also still seeking to ensure Rome’s stability and that the things he had accomplished or implemented in his reign wouldn’t be tossed to the wind. The alternative to a clear line of succession might’ve been a simple resumption of power struggles and civil wars upon his death.

One of the saddest elements of Augustus’ later life in fact were the premature deaths of his intended heirs and his struggle to resolve the succession problem: which eventually resulted in his stepson Tiberius becoming his successor.

Having lived a long and extraordinary life, Augustus died at the age of 75: most sources say from natural causes, although there were rumors that his longstanding wife Livia had poisoned him. This implication of Livia has been a subject for debate; though the idea of her having poisoned has been popularised more in modern times, such as in Robert Graves’ classic novel I, Claudius (and the brilliant 1970s BBC series of the same name).

As for the question of whether Augustus was a force for good or a force for ill, it is still debated to this day and will never have a definitive answer.

But the truth, as in most things, probably rests somewhere in the middle. He was both; and, arguably, much of what we might consider ill about what he brought about is to do with the actions and character of later emperors and regimes rather than the actions of Augustus himself.

Anthony Everitt, in Augustus: The Life of Rome’s First Emperor (2006), argues that Augustus is in fact a contradiction; and that these contradictions don’t need to be resolved by historians, but rather seen as dual natures of his own personality. ‘Selfishness and selflessness coexisted in his mind,‘ he writes. ‘While fighting for dominance, he paid little attention to legality or to the normal civilities of political life. He was devious, untrustworthy, and bloodthirsty. But once he had established his authority, he governed efficiently and justly, generally allowed freedom of speech, and promoted the rule of law. He was immensely hardworking and tried as hard as any democratic parliamentarian to treat his senatorial colleagues with respect and sensitivity. He suffered from no delusions of grandeur.’

And yet, far from suffering no delusions of grandeur, he was also a divinity and sought to impose his will on the world and to exercise power over all society.

‘The deeds of the divine Augustus, by which he subjected the whole wide earth to the rule of the Roman people…’ says the introduction to copies of his all-important ‘Res Gestae’. But of course we cannot make the mistake of judging a 1st century figure through the lens of 21st century sensibilities.

That is in fact one of the reasons why such remote figures as Augustus, Claudius, Tiberius and co are so endlessly fascinating: because they lived so long ago and in such a different world that we don’t feel any need to make absolute judgements on them or take moral positions regarding their actions.

I have often wanted to get into the mind of Augustus: often wished I could go back in a time machine and interview him. Did he really believe in the Republic, even as he was helping consign it to history?

And did he think he was the founder of an empire that would last for thousands of years or did he sense, in his heart, that it would collapse much sooner than that? Did he suspect his family dynasty would end after only a handful of successors? And what would he think if informed that his temples and monuments, his busts and coins, and biographies would still be the subject of interest and analysis 2,000 years later and long, long after Imperial Rome had vanished?

Well, one thing we do know is that Augustus wasn’t modest: and he wanted to be remembered for as long as Rome stood.

The ‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’ (‘The Deeds of the Divine Augustus’) is the famous funerary inscription, providing a first-person record of the life and accomplishments of Augustus. The inscription itself is a monument to the establishment of the Julio-Claudian dynasty that was to follow Augustus. According to the text it was written just prior to Augustus’ death in AD 14; but it is regarded by experts to have been written years earlier and likely went through many revisions.

Augustus left behind the text for the inscription with his will, which also instructed the Senate to set up the inscriptions. The original, which has not survived, was believed to have been engraved on bronze pillars and placed in front of Augustus’ mausoleum. Numerous copies of the text were made and carved in stone on monuments or at temples throughout the empire, some of which have survived. A nearly full copy, written in the original Latin and a Greek translation, was preserved on a temple to Augustus in Ancyra (Ankara, Turkey).

The Res Gestae is especially significant because it gives an insight into the image of himself that Augustus portrayed to the Roman people; an image that was carefully cultivated and maintained over his lifetime and beyond. Over the centuries, various inscriptions of the Res Gestae have been found across what used to be the Roman Empire. The first section is concerned with Augustus’ political career, recording the offices and honours he held (like an ancient WikiPedia page, albeit a self-written one). To demonstrate his apparent humility, Augustus also lists the numerous offices he refused to take and privileges he refused to be awarded.

The second section (paragraphs 15–24) records his donations and kindnesses to the citizens of Italy and to his soldiers, and all the public works and gladiatorial events he commissioned. The main motive for this section of the Res Gestae is to point out that all of these things were paid for out of Augustus’ own funds.

The last section (paragraphs 34–35) consists of a statement of public approval for the deeds of Augustus.

No doubt, the text provides a highly idealised, glossed over version of his reign: and probably one that he dictated in part himself.

_________________

Beyond historical accounts and later academic analyses, Augustus/Octavian has also been portrayed in various ways. In modern terms, the two portrayals that come most to mind are in the classic I Claudius TV drama series (in which he is portrayed by Brian Blessed) and in the more recent HBO/BBC ROME series.

Interestingly, even using these two portrayals, Augustus is portrayed very differently. In I Claudius, he is depicted as a kindly, even jolly, elder statesman type and patriarchal figure. He is fair, high-minded, sympathetic, and generally portrayed as the Good Guy (contrasted to his wife Livia’s coldhearted scheming). In ROME, however, he is a much more a cold, calculating, ruthless figure, albeit one who isn’t corrupt but supremely ambitious.

Interestingly, ROME depicts him as the child Octavian for the entirety of the first season (and some of the second), showing him growing up, learning, formulating his thoughts and ideas, and watching everything going on around him, including the Civil War. We often see him watching political clashes and schemes from behind a corner or in the background, observing the dynamics of the Roman state as well as the corruption. He is frequently shown watching his uncle Julius Caesar. Then in the final several episodes of the series, we see the older Octavian – a young man beginning to carve out his path to power.

The fascinating thing about ROME’s handling of Augustus is that it he is ultimately the central historical figure of the show in the end: the series depicts how Octavian the boy schemes and navigates the travails of late Republican Rome until he emerges finally as the last man standing, and in a position to take control of Rome’s future and enact his will.

The interesting thing is that if you take both depictions together – that is to say, you start with the ROME depiction and then go onto I Claudius – you probably end up with something close to what the historical consensus ends up as: a ruthless, ambitious young Octavian who, after his consummate victory and attainment of absolute power, grows into a more pragmatic nation builder and overall less aggressive and more sympathetic man.

But reading the Roman writers’ take on Augustus is always the most interesting.

Tacitus, writing decades later, appeared to be no fan of Augustus’s reign. Livy, who was on good personal terms with Augustus and would also be something of a mentor to Claudius, is regarded by some as being an unreliable source for information on Augustus on account of his personal connection.

Livy believed, as Augustus did, that there had been a great moral decline in Rome: but he actually didn’t believe that Augustus could reverse it.

He believed, however, that Augustus was necessary, but only as a short term measure. Livy’s view can actually be seen to have been validated by much of what happened in Rome after Augustus’ death; in as much as the ‘necessary’ Augustus may have countered the ‘moral decline’ during his reign, but clearly hadn’t entirely reversed it, as there were scandals and depravities that unfolded post-Augustus that were in excess of even anything that had gone prior to his reign.

Suetonius has a largely flattering view of Augustus, which included excessive mythologizing, such as the suggestion of a virgin birth. Some of his portrayal of Augustus more resembles the manner in which some later Christian Gospel writers would mythologise the birth of Jesus (who was, as it happened, born during Augustus’ reign).

For example, he also suggests that in 63 BC (the year of Octavian’s birth), during the Consulship of Cicero, several Roman Senators dreamt that a king would be born and would rescue the Republic.

Even that close to his lifetime, the character and life of Augustus was already inextricably bound up in myth, religion and propaganda – much of it of his own making – so that recovering the real person from all of these layers is ultimately a difficult task.

But one gets the impression that Augustus himself might’ve liked that.

Of the many lost works from Roman writers, the one we might most dearly wish to have survived (or to yet come upon in some spectacular find) would be the history of Augustus’s reign known to have been written by Augustus’s grandson, the Emperor Claudius himself.

To read those texts, written by a member of the family, someone who knew Augustus (and was also the grandson of Mark Antony, no less) and who himself would rule as Emperor, would be utterly fascinating.

More: ‘MUAMMAR GADDAFI: A Psychological Profile of Man, Myth & Reality…’

Suddenly much to take-in via media with this, a welcome less-contemporary relief? Yet, how much about now, is specifically about what came via Rome-then? Get the world’s a complex mix of wider, progressive influences but instinctively hunch, dark roots happened soon after – yes, y’guessed – Jesus birth. Recently noted, M. Heiser popularising the theory, was on September 11, 3 BC. (OK – many say, fantasy-ised). Therefore, the post-Augustus period. Mithras and mysterious and how Rome took on the Greek mantle and went even one-step NWO mad-er. Comparisons in our midst abound. So thanks for this fine write. Will use as a springboard into trying to find the infections and keys. Wanting to be found and exposed -yet- secrets and subterfuge. Best compliment; makes me want to know more, about this man and era.

Yeah, I’ve seen it strongly suggested either 3 or 4 BC. Something to do with the Christian/Roman historian’s calculations being off because he was dating based on the reign-lengths of Emperors and he knew that Jesus had been born a certain number of years into the reign of Augustus – but he had forgotten that Augustus had also ruled several years under the name ‘Octavian’ and so he was four years or so off in his calculations.

Yeah, in terms of less contemporary content like this, I’d love to do a lot more of it. The problem is that no one (except you and one or two others) will read it. Still, I guess, better to write about what you’re genuinely interested in than produce content just for ‘hits’.