It is, has been and will be, one of the most controversial storylines in Marvel Comics’ history. It is probably the most controversial event in the mythology and history of Captain America.

The road to Secret Empire has been convoluted, compelling and well planned out. In this article, I’m tracking back across the first few months of that road.

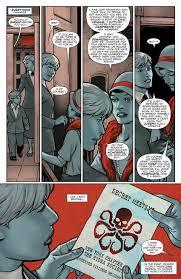

Written by Nick Spencer, Captain America: Steve Rogers #1 seemingly gave us one of the most surprising revelations in Marvel Comics’ recent history; Steve Rogers, the epitome of all that’s good and wholesome in the Marvel Universe, is an agent of Hydra.

Or at least we’re given that impression.

The story in #1 was split between past and present and served to introduce new elements to what is already one of the best-known backstory’s in comic books. In flashback mode, we discovered that a Hydra operative named Elisa Sinclair intervened in Steve’s mother’s life, specifically saving her from her abusive husband. Sarah and her son, the future Captain America, go to dinner with her, and we see Sarah being given a pamphlet bearing the Hydra logo.

Back in the present, we witness Rogers commit an act of treachery right before two words emerge from his mouth that we never imagined we’d ever hear him speak: that phrase recently made all the more famous by the Agents of SHIELD TV series – “Hail Hydra”.

Everyone went crazy, reaction was all over the web and Nick Spencer even allegedly received death threats. I had said at the time of reading Captain America: Steve Rogers #1 that – in the long run – there was no way Steve Rogers was going to be a Hydra agent; and that there would obviously be some form of get-out-clause for the writers down the line.

What that opening chapter did, however, was to create a stunning mystery, turn the established mythology on its head, and leave us all scratching our heads and trying to work out what was going on and what it was going to mean.

That’s a hell of a successful single-issue of a comic book, let alone a first issue. And all the media – and social media hype (and/or backlash) ensured maximum publicity and anticipation for the story that Spencer was proceeding to tell.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #2 opens with the Red Skull’s monologue, which is particularly good, as Schmidt deconstructs Rogers’ path and psychology in just a few panels. The full page image of Schmidt holding the Cosmic Cube is a magnificent visual.

What then unfolds is the Red Skull giving us a first-person narrative shedding light on the real nature of what’s been going on. And in no time at all, we get an explanation for Steve Rogers’ “Hail Hydra” moment that had caused such controversy among comic-book readers and Cap fans.

The Kobik child was always an interesting idea, bringing with her a lot of story potential. A character with the ability to rewrite history and alter the existing timeline, so to speak, could – if badly handled by writers – become an annoying deus-ex-machina.

But, at the moment here, and as applies to Cap, this is reasonably interesting stuff.

Some of the Red Skull scenes or dialogue are a bit on the silly side, as often happens with this character. But the Red Skull is basically the most irredeemably evil character probably in all Marvel Comics – and, lacking all charm or wit, he can become a little hackneyed. But he is the staple villain intimately tied to Captain America, so there’s no getting around his stature as a character and the need to revolve stories around him (he’s also the creepiest – and seeing him with any child, let alone a cosmic superbeing with god-like powers, ramps up the creep factor).

And in these highly toxic times in the real world, with Far-Right, ultra-nationalist and even Neo-Nazi parties and figures re-emerging across the Western world, the Red Skull becomes an extremely useful vehicle through which writers can explore, mirror or just generally comment on current events and worrying trends.

That has certainly been happening and not just in these pages: but Spencer’s handling of this Captain America: Steve Rogers title in particular is clearly utilising both the Red Skull and Steve Rogers as a way of exploring those issues.

And it’s a good example of the extent to which high-profile comic books can really act as important commentary or reflection on significant socio-political events.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #2 begins to retroactively answer the uncomfortable questions raised in #1 – just as I said it would when knee-jerk people were condemning Nick Spencer for turning Cap into “a Nazi” and refusing to even give the story time to develop.

As it happens, we didn’t need to wait long at all.

Onto Captain America: Steve Rogers #3 and, as with #1, the material set in the 1920s is possibly more interesting than the present-tense narrative.

The authentic look and feel of these 1920s scenes really helps create a fuller scope to the story. That said, this entire storyline is a little unsettling – but in the way it is no doubt intended to be. Everything, from seeing Steve Rogers bow to the Red Skull and refer to him as “Supreme Leader” to seeing a group of innocuous-seeming ladies in 1920s fashion casually chant “Hail Hydra”, serves to both trouble us and to prod at our sense of reality.

This is perfect, however, as Steve Rogers‘ own sense of reality – or, more accurately, the nature of his reality – is what is being manipulated.

On the subject of Elisa Sinclair, Sarah Rogers and those 1920s scenes, this again is where Nick Spencer’s use of Captain America as social commentary and as exploration of real-world current affairs really proves pertinent and engaging.

Just as Donald Trump‘s ‘America First’ inauguration speech in February (which was deliberately echoed in Captain America’s SHIELD inauguration speech in Civil War II: The Oath) was deliberately making reference to the Nazi-sympathising ‘America First’ organisation of the 1930s, so too are we here in this story going back to the early 20th century to explore the American Nazis of the day – and to really get the sense of how these forces and secret societies don’t emerge from nowhere but simply bide their time, always there somewhere in the shadows, waiting for the right conditions and circumstances to emerge into the light and make their play for power.

That’s generally always been the thing about Hydra anyway; but here in this title, Spencer makes this more tangible and meaningful than anything I can recall previously reading.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #4 continues the steady development of the complex storyline; though it arguably gets a little too complicated and crowded for a single issue, with everyone from Quasar to Taskmaster showing up, all while we get S.H.I.E.L.D controversies going on, and the central Captain America part of the story.

All of this AND it’s meant to act as a Civil War II tie-in, which it mostly isn’t – despite the misleading Rogers/Stark/Danvers cover and a shoe-horned and mostly unconnected appearance by the Inhuman Ulysses.

Still, in spite of this sprawling hotch-potch of goings-on, the central, Rogers-based story is still developing with suitable intrigue here, as Cap’s own motivations and agenda are starting to reveal themselves. Cap killing in cold-blood early on in this issue is a little disconcerting, especially the casualness of it.

On the other hand, his revealing – to Doctor Selvig – that he in fact isn’t under the thumb or sway of the Red Skull is an interesting twist, which raises the intrigue levels and keeps us guessing.

What Nick Spencer certainly isn’t doing in any of these comics is allowing the story to become stale, predictable or cliched.

And the material set back in the twenties with boy Rogers and Elisa Sinclair continues to provide even more scope – along with a noire flavor – to the intrigue.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #5, on the other hand, ties in to the Civil War II storyline much more meaningfully: and it does so very well, in fact.

Not only do we get the Rogers’-eye-view on specific scenes from the mainline Civil War II series (which makes for a fun crossover companion), but we learn that machinations on this side of the MU are impacting directly on what’s going on in the Civil War II pages.

Some of this works rather nicely. Some of it strains credibility just a little.

For example, the idea of Cap sneaking into New Atillan to kill Ulysses kind of works: but the idea that he is there, hiding in the shadows, watching Stark sneak into New Atillian to kidnap Ulysses (see Civil War II #2) is a bit too much. I mean, that’s a crowded scene by now: and it’s a little incredible to think that neither Tony nor Ulysses nor any of the Inhumans detected Rogers hiding there in the room.

This is perhaps an example of writers running away with things a little too freely.

Similarly, the idea that Rogers and Selvig were directly responsible for Dr Banner’s experimenting on himself (the thing that led to Banner’s death at the hands of Hawkeye in the pages of Civil War II) is a nice little crossover touch. On the other hand, the idea that they could’ve known doing this would lead to Hawkeye killing him (particularly as Banner had to first go to Hawkeye and ask him to kill him if things got out of control) seems a little far-fetched and it tends to undermine any organic feeling to the story developments.

While I am genuinely and substantially enjoying the Civil War II title, it seems as if the parallel situation of this Captain America storyline might actually be a complication that the Civil War II event could’ve done without.

On one hand, Marvel managing these two parallel stories and trying to make them compliment each other is admirable; on the other hand, I’m not sure it necessarily works that well. Both stories are genuinely good in their own right – together, I’m not so sure. Captain America: Steve Rogers #5 tries its best to make this work, primarily by acknowledging that Rogers and Selvig are worried about Ulysses’ visions and may need to postpone or delay their plans until the Ulysses situation is resolved.

But it feels, essentially, like a holding action to delay progression of this Steve Rogers story until the Civil War II event is over.

Aside from the Civil War II elements, Rogers’ own intrigues continue to make for engaging reading in their own right, however. And the nineteen-twenties material is, again, a welcome element in the mix. In this issue, this consists of boy Rogers being delivered into what is essentially a Hydra indoctrination/training school, essentially giving us a look at the psychological conditioning that is responsible for the Kobik-inspired Steve Rogers we’re currently seeing in our present. Daniel Whitehall’s presence is a good touch to this too.

What is generally unnerving about this side of things is how clearly it feels like a Nazi Youth brainwashing programme. No doubt, that’s the point.

This is expanded on further in Captain America: Steve Rogers #6, as we see the boy Rogers going through the hardships and isolation of Hydra youth ‘re-education’.

For die-hard or long-time Cap fans and fans of his mythology, some of this might be tough reading. If you’re particularly invested in or precious about the classic Captain America origins story, then this re-writing of that story might be hard to swallow (hence some of the negative fan reaction).

Understanding, however, that this is essentially even a ‘re-writing’ of that history in terms of the actual in-story paradigm itself should help alleviate that distress: the Kobik girl literally is re-writing Rogers’ history and what we’re seeing is – kind of – an alternate-reality replacing our more familiar Rogers’ reality.

Which is a bit confusing, as it isn’t clear how this re-shaping of Rogers’ reality is so specific to Rogers – seemingly without effecting other characters’ timelines or life-stories, despite the extent to which Steve Rogers’ life story and actions should, in theory, have impacted on the course of other characters’ lives.

I’m sure, somehow, it makes sense and I just haven’t properly understood it (wouldn’t be the first time).

The Civil War II elements on Captain America: Steve Rogers #6, however, are on better ground than in the previous issues. It is actually making re-reading the Cap moments in the Civil War II title more interesting. Watching Rogers manipulate everyone is interesting too.

Here, in particular, his manipulation of Tony Stark is more than a little Machiavellian, as he cynically prods and pokes under Tony’s skin to make him question everything he’s doing.

He even takes a particularly low jab by asking Tony if he’s been drinking again. This is where he wants Tony, as he says himself – ‘Off-balance, questioning yourself’.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #7 has the series reaching a new high.

Indeed, here in #7, any notion that the series has been only metaphorically or symbolically exploring real-world contemporary politics goes out the window: this story is overtly, explicitly dealing with real-world, current geo-politics, taking in not only the rise of ultra-nationalist politicians and looming shadow of fascism, but the War in Syria, the refugee crisis and the Islamic State terror group too.

This isn’t even subtle, but overt.

The Sokovia presented in this story is clearly Syria, with the corrupt regime (according to this narrative anyway) struggling to stay in place against an uprising by Hydra-backed ‘freedom fighters’ (ISIS/Daesh, essentially), while S.H.I.E.L.D and the Good Guys are struggling morally over whether to support the corrupt regime in order to stop the terrorists from winning and gaining more territory.

We even see Rogers and Romanov freeing a ‘freedom fighters’ from prison and promising to arm him and his fighters, just as the US did in real life with various terrorists in Syria. Perhaps, given this comic book’s closeness (time-wise) to the events in Aleppo, this was really trying to recapture some of what was happening in the real world.

Some of this is, unsurprisingly, very grim: an image of men being hung next to a Hydra symbol, for example.

The Red Skull conversation with the regime General is a particularly compelling moment, as we learn what the Skull’s game in Sokovia is. Some of his speechmaking, as in previous issues, is also designed to ape or mirror some of the rhetoric and speechmaking we’ve seen in recent times from real-world populists and nationalists.

I’ll say again: although he can be a very silly-feeling villain a lot of the time, the Red Skull – on his day – is still the most evil villain in Marvel books and one of the most scary.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #8 doesn’t feature Schmidt, but fleshes out substantial new/revised backstory for Baron Zemo in the past, while the present-tense plot develops further, centering on Carol Danvers, Alpha Flight, Quasar and the Chitauri.

The latter is a lot less interesting than the former; however, it is a credit to this series that it effectively juggles so many balls, bringing in so many different players, connections and situations all the time.

The development of Avril/Quasar and her immense powers is interesting, while Cap’s actions and motivations continue to intrigue.

Really, however, it is again the material set in the past that provides the most interest. The reworking of Rogers’ history with Zemo is fascinating, while in general the scenes involving Elisa Sinclair and the 1920’s Hydra cabal make for fascinating reading. In particular here, her casual dismissal of Hitler as “not the one we’ve been waiting for” is intriguing for how far above even Hitler and the Third Reich they consider themselves, with the implication that Hitler and the Nazis are almost minor fodder in the context of the greater cause of Hydra.

On the other hand, the suggestion that Steve Rogers is the Hydra Messiah – even above Adolf Hitler – gets us back to the underlying idea that was making a lot of fans uncomfortable right from the start of this title.

Which brings us fill circle and back to the question of whether this whole story is a ‘sacrilege’ against the Captain America mythology – or whether it’s a genius concept that enables high-quality storytelling.

Given the sheer sublime quality-level that Spencer has achieved in this remarkably long-form story, I would be astonished if anyone still thinks this was a bad idea or that it should’ve been a no-go area. What Spencer and co have achieved with this entire story – and where it is ultimately leading – is absolutely epic in scope.

But, moreover, the real joy is in getting there: it’s in all the details, all the steps along the way, and all the superb, gripping storytelling therein.

And at this point – in Captain America: Steve Rogers #1 – 8 – we’re haven’t even got going properly yet, with so much more to come. And yet even at this point, the storytelling and execution is on a level so good that ‘justifications’ ceased being pertinent a long time ago.

This is superb, compelling stuff.