History is cyclical, they say.

Or, to quote George Lucas, “it’s like poetry, it rhymes.”

That idea has been very much in mind as I’ve watched this Imran Khan saga and the degradation in Pakistan’s politics unfolding.

I examined the important details concerning Khan’s removal from office here: and, crucially, his allegation that the US was behind a conspiracy against his government.

What’s fascinating is how much this state of affairs echoes another key moment in Pakistan’s tumultuous and painful history: to see that there are certainly interesting resonances or parallels that can be drawn between those defining traumas in Pakistan’s history and the present state of affairs.

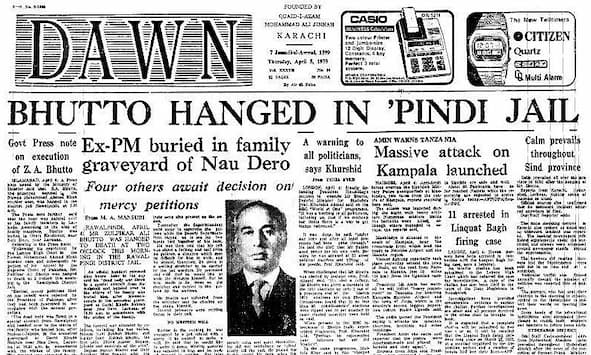

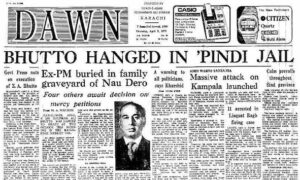

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto remains Pakistan’s most popular leader to date: a figure whose judicial murder is still mourned by thousands every year in Pakistan.

Among other things, Bhutto had been unhappy about Pakistan’s relationship with the US and was pushing for the country to be more independent. In essence, Bhutto – who was more or less a secular leader and a moderniser, as well as a left-leaning politician pursuing policies centered on social justice – was committed to preventing Pakistan being a puppet state under foreign dominance.

We can see the echoes of this in Imran Khan’s recent statements about Pakistan not being the West’s “slave”. Khan, like Bhutto, has talked frequently about Pakistan being free to pursue its own foreign policies, for example: which was, again, a big part of why Khan recently refused to denounce Russia and why he chose to go to Moscow at what was – through Western eyes – the worst possible moment.

Suspicions have long existed in Pakistan that Bhutto’s removal from office – and his execution on the orders of the military dictator Zia-ul Haq – might’ve been at least tacitly sanctioned by the US.

Declassified CIA documents at the very least show that the US was fully aware of the likelihood of Bhutto being put to death.

All of this generation-defining crisis in Pakistan stemmed from Bhutto and the Pakistan People’s Party’s main opposition – primarily an alliance of conservative Islamist parties – refusing to accept Bhutto’s sweeping majority win in elections and accusing him therefore of vote-rigging. What ultimately followed, along with Bhutto being put to death by hanging in 1979, was years of martial law and military dictatorship.

It is worth noting, historically, that the dictatorship’s friendly disposition towards religious conservatives and fundamentalists was something that directly benefited the US in the Cold War: because the Pakistani military was the major facilitator of the Mujahideen holy war in Afghanistan against the Soviets, which was of course a major part of the US’s anti-Soviet policy at that time.

We won’t bother to get into the pros and cons of the US or Pakistan’s Afghanistan policies here, as that’s a whole separate subject. There are good arguments for why the US supported the Mujahideen’s justified war against the Soviet invaders, as well as good arguments for how the whole thing ended up being a disaster for everyone in the long run.

None of this proves – or means – that the US was directly involved in the removal of Bhutto from office or in his execution: but it’s easy to see how the US would quietly sit the matter out and be perfectly happy for the military to put Pakistan’s duly-elected (and most popular) political figure to death.

Bhutto himself had said he was being targeted by what he’d called the two hegemonies over Pakistan’s fate – the internal one, being the military and the elites, and the external one being the United States.

It is entirely possible – and would be somewhat in keeping with the historical context – that Imran Khan may have been ousted by the same marriage of interests: albeit in a less horrible manner.

This video by TCM Originals lays out some of the reasons for suspecting the US of having quietly sanctioned the moves against Bhutto; including elements that are strikingly similar to the narrative that Imran Khan has been putting forward in the last few weeks – such as perceived threats from the US embassy and even reference to a letter or document that Bhutto was planning to expose.

These obvious parallels suggest either that a very similar series of events has genuinely unfolded or that Imran Khan has actually fabricated – or at least carefully framed – his own narrative of these events so as to deliberately resemble the ousting of Bhutto forty years ago (knowing, of course, how much the injustice done both to Bhutto, and by extension the Pakistani people, has resonated in the public consciousness for so long).

It’s difficult to tell for sure which of those is the truth.

But it’s a fascinating consideration. Hopefully, however this whole thing unfolds, Khan’s fate will be different to the unfortunate Bhutto’s.

Still, history doesn’t just inform the present: it often seems to be in a repeat cycle. It may simply be that there’s really nothing new under the sun, and everything has already transpired before.

AFGHANISTAN: The US/NATO’s Failed 20-Year War – What Was It All About…?