On February 3rd, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi was murdered in his home in Zintan, Libya.

Four unidentified gunmen invaded the property and opened fire. The 53 year-old son of the late Muammar Gaddafi is reported to have tried to fight back, but was ultimately killed along with several others.

The identity of the assassins remains unknown, as does the source of the murder plot.

But Saif al-Islam had been at risk of assassination for many years, especially once he’d announced his intention to run for president in the chaotic, dysfunctional country.

I made that point here several years ago, after an earlier assassination attempt following his initial release from captivity. The same forces and interests that had driven the collapse of the former Libyan state were not going to be willing to allow the son of Gaddafi to return to any sort of political prominence or influence.

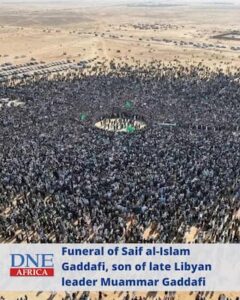

His funeral was attended by thousands. As the North Africa Post tells us, ‘His funeral attracted thousands to Bani Walid, a stronghold of pro‑Gaddafi sentiment, where France 24 reporting noted a strong sense of nostalgia for the pre-2011 era. Local imagery placed Saif al-Islam in a martyr-like role, highlighting how deeply some communities reject the post-revolutionary order…’

Indeed, Saif himself had been targeted by NATO forces for assassination during the events of 2011: just like the attack that had led to his father’s brutal murder, Saif’s convoy had been struck by NATO in October 2011 – a number of people were killed, but he survived.

Post-Gaddafi Libya is still without a national government or functioning system – fifteen years after the bloody uprising and NATO intervention that destroyed the old Libyan state.

The elections that had been called for – and that Saif Gaddafi had intended to participate in – have been continuously postponed in Libya since 2018. Saif’s own announcement of his intention to seek office originally related to elections that were meant to happen in 2021, but never did.

Uncoincidentally, his murder in Zintan last week occurs with the process of elections finally scheduled to begin in March/April this year.

It’s not too much of a leap then to think that some faction or another decided that now was the time to eliminate Saif Gaddafi from the equation.

The primary forces in Libya today are a UN backed ‘government’ in the east and the warlord (and former CIA asset) Khalifa Haftar. Curiously, the murder of Saif Gaddafi came mere days after a January 28th meeting in France’s Elysee Palace involving the two sides, both of whom viewed Gaddafi as a major problem.

Given France’s central role in the Libya conspiracy in 2011 that saw the collapse of the Gaddafi era, is France still wielding influence in these affairs? Interestingly, ‘Reports of a Paris meeting had circulated in the media in late January, but there was no official confirmation from any of the parties involved… the meeting was coordinated by the United States and France…’

What happens in April remains to be seen. Elections again may end up collapsing or being postponed again. There can’t be many Libyans left with any faith.

Ironically, Saif al-Islam had been calling for elections even when his father was still alive: and again during the 2011 catastrophe. It remains an underreported fact that the former Libyan state under Gaddafi had offered not just a ceasefire but also immediate elections in 2011 in order to end the civil war and prevent the country’s collapse: it was France and Britain that rejected the plan and kept the war going instead.

I covered that, and many other things, in The Libya Conspiracy here.

Fast forward fifteen years and Saif al-Islam was arguably the only real figure capable of generating any kind of popular support. For some in Libya, his death is also the death of hope.

In 2017, I spoke to JoAnne Moriarty, who was an eyewitness to the events of 2011, having been a prisoner of Al Qaeda. She later became an activist in Libya. When I asked her about the future in Libya, she said unhesitatingly; ‘Saif is the main player on the stage as the most unifying leader for Libya – there is no other. He will be the next leader of Libya…’

And that was the threat he represented.

Libya since 2011 has been a strife-ridden, war-torn country run by criminal organisations, war lords and foreign entities. They all have their hands in the spoils. Saif was an intolerable risk to that.

In 2015, he had been sentenced to death by a court run the ‘Libya Dawn’ militia in Tripoli: but the sentence was eventually overturned and he was granted amnesty.

He remained, however, wanted by the International Criminal Court on dubious charges of ‘Crimes Against Humanity’ that had been issued in the midst of the 2011 Civil War. The charge had made little sense, given that Saif had held no formal position at that time, either in the government or the armed forces – and therefore couldn’t have been part of the chain of command that had led to any alleged crimes described.

The strange irony about Saif’s story is that he was, in theory, everything the West should’ve wanted in Libya. A reformer, a moderniser, Western educated.

For a spell, it had seemed like he was well liked in European elite circles. He had been a guest at Buckingham Palace, had spent time with the Rothschilds, had had relationships with people like Klaus Schwab, etc. Bizarrely, it was even later reported that he had been approached by supermodel Naomi Campbell on behalf of one Ghislaine Maxwell, who wanted to visit Libya on her yacht.

It isn’t known if that trip ever happened: or indeed what Ghislaine really wanted in Libya.

He was credited as the main influence on his father’s rapprochement with the West in the 2000’s, and seen by some as the key figure in Libya’s movement away from pariah state status and towards international acceptance.

However, Saif himself later came to view the very rapprochement he himself had advocated with the West as having been a mistake: more to the point, as having been a trap to lure Libya into a false sense of security.

Libya giving up its weapons programmes and failing to maintain or develop stronger armed forces were also later seen by Saif as having been a mistake: though they were the key basis for the rapprochement with the Western powers.

It was clear from his own statements during the catastrophic 2011 crisis that Saif Gaddafi deeply regretted his role in inadvertently leaving his father’s government vulnerable to foreign-orchestrated conspiracy.

He not only realised that he had been naive: he accused the Western governments of duplicity and betrayal. He must’ve wondered if Western political elites had in fact used him deliberately to help soften up Libya for exploitation.

If any questions are raised concerning his flirtations with Western elites in the 2000s, it’s worth noting that Saif al-Islam never abandoned Libya.

In the midst of the bloodbath in 2011, he could’ve easily fled the country. He could’ve gone into exile, or sought sanctuary in various places. He could’ve even renounced his father and tried to distance himself from whatever accusations were being levelled at the regime.

Instead, he stayed and fought: both to rally the loyalists in the country and to continue to represent the Libyan state to the international media.

Again, following the murder of his father and the collapse of the old Libya, he could’ve gone into exile and tried to stay safe.

Instead, upon being released from prison he immediately announced his intention to be politically active and to try to oppose the chaotic forces that were now loose in the country. Surely knowing that it could very likely cost him his life.

On February 6th, it finally and inevitably did.