Are handwritten letters on the verge of extinction? And will anyone know to mourn their passing away from modern life?

Some time ago, as part of a World Book Night event, Russell Brand took part in ‘Letters Live’ at London’s Southbank centre; he read a poignant handwritten letter that had been written by Iggy Pop years ago to a troubled Parisian fan on her 21st birthday.

Among others also involved in the event were columnist Caitlin Moran and IT Crowd actor Matt Berry reading a letter from Elvis Presley to Richard Nixon.

The event was in part a celebration of the tradition of letter writing itself, which is a dying tradition in the modern age of emails, Social Media and text messaging. Certainly the art of handwritten correspondence in a meaningful sense is something that’s long been in decline.

There’s a generation below mine now, many of whom will have never written or received a handwritten letter in their lifetimes.

But this decline in the practice of handwritten correspondence doesn’t just have implications for people’s personal lives: it has cultural and historical implications too, as we will explore.

I’m as guilty as anyone of contributing to the collective extinction of handwritten correspondence too; I can’t remember the last time I wrote on paper to anyone.

It simply seems like one of a number of past arts that will eventually be made fully obsolete by modern technology. It’s difficult to ascribe sentimental value to an email on a screen, which soon gets lost amid an endless flood of other emails on a daily or weekly basis. And Social Media platforms, primarily Twitter and Facebook, are even worse; even more devoid of any lasting sentiment.

I do also find myself glad I grew up in a pre-Internet era; that I grew up without being consumed by Facebook, Social Media and all the rest of it. Although I am now too lazy and too ‘assimilated’ to bother actually writing to anyone anymore myself (and also almost everyone I can think of would find it weird to receive a handwritten letter in the post), there is no doubt that most forms of electronic correspondence are simply short-lived – they get superseded so quickly by subsequent correspondence, whereas old-fashioned letters are probably more likely to be kept somewhere, even if forgotten for a long time.

This temporariness of digital communication essentially suggests the electronic age of communication imparts very little to posterity.

I forget the content of emails within a day or two: but there are some handwritten letters from years and years ago that I still remember in detail. Some of this might have to do with the impact of tactile and sense memory; the look of ink, the feel of paper, or even the tactile ritual of opening and perusing a handwritten piece of correspondence.

Or maybe it’s that a handwritten letter feels so much more personal and focused than words on a screen. I’ve had reasonably meaningful or lengthy exchanges with people over email; but they just don’t seem to register as strongly in the consciousness or in memory.

And they don’t get held on to in the same way: I still have some letters from twenty years ago. Letters, for example, from my aunt when she was living abroad: I was a child still and she wanted to maintain our relationship so she wrote to me every year.

A while ago, I was going through some dusty drawers in my grandparents’ house and I discovered a love letter my Grandfather wrote to my Grandmother – from the 1950s. It was discoloured and the ink was fading – and it felt like excavating an ancient artifact – but it was a real piece of my family’s history from long before I was born; and it made me feel more connected emotionally to both of them.

And that’s me just talking about examples of letters meaning something on a personal level.

When we get to the cultural level or the historical level, we enter a whole new arena.

Beyond the issue of personal correspondence and items of our own personal sentimental value, the special place held by handwritten correspondence in our culture and history remains highly significant.

There is an understandably enduring and ageless fascination with letters and correspondence relating to interesting cultural or historic figures, such as Charles Dickens, Malcom X and Martin Luther King, among many, many others. Such items can shed great light on said figures or on the times they inhabited or the events they are associated with.

The significance of letters from the World Wars, for example, or surviving letters from the Napoleonic era or the American Civil War, or even as far back as Roman times, cannot be overstated as a historical resource.

Surviving letters written by Adolf Hitler, for example, or correspondence between Churchill and Roosevelt, provide tremendous insights into not only decision making and maneuvering, but the characters and ideologies of key figures in the war.

One of the most fascinating, curious letters from that same time was the famous ‘letter of friendship’ written by Mahatma Gandhi to Adolf Hitler. Dated Christmas Eve 1940, Gandhi urges the Fuhrer towards a peaceful resolution to the conflicts of World War II.

“Dear Friend…” the letter begins, “That I address you as a friend is no formality. I own no foes.” The letter, a strange mixture of noble sentiment and pragmatic motivation, goes on to urge peace, and ends “Your sincere friend, M. K. GANDHI.”

One of the enduring cult figures of the early twentieth century and a person of continuous fascination to me, T. E. Lawrence, was remarkable among other things for the quality of his letters. Not just that they were interesting and always written with the sort of poetic flourish to be expected of a writer, but again that they provide a rich insight into Lawrence’s mind and his relationships with others.

Among his numerous letters were correspondence with such figures as the author Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon, and Bernard Shaw, as well as fellow archaeologists like Gertrude Bell and public figures such as Winston Churchill. Some of these provide not just insight into the lives and thoughts of well known or historic personalities, but also into major turning points in history; such as, in the case of Lawrence or Gertrude Bell, the Arab Revolt and the making of the modern Middle East.

There are some endearing contemporary examples of correspondence that in fact serve to humanise very larger-than-life figures. Two of these I’m thinking of concern Fidel Castro and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi.

Odd as it sounds, Gaddafi had a Jewish pen-pal who lived in Brooklyn. Louis Schlamowitz had actually begun writing to Gaddafi way back in the 1960s and the letters only stopped in 2011 when the foreign-backed uprising in Libya began, at which time the Brooklyn-based florist was 81 years old. What is remarkable, and kind of endearing, about this story is that Gaddafi always wrote back, maintaining this pen-pal correspondence for decades. “He was a good pen-pal,” the elderly florist said. “I felt it was very nice of him to take the time to write back to me, because I’m nobody special.”

Mr Schlamowitz, who also exchanged letters with Marylin Monroe and Richard Nixon among others, said his correspondence with the Libyan leader aroused suspicion from the FBI and American agencies who visited him to ask what he was playing at.

A Christmas card from Gaddafi, written around 2000, thanked Mr Schlamowitz for his “friendship through the years”.

And when he was 12 years old, Fidel Castro wrote a letter to then US President Franklin Roosevelt (source). In it, the future Cuban dictator and figurehead asked Roosevelt for a $10 dollar bill, claiming he wanted one because he had never seen one before. In the handwritten letter, the young Castro also congratulated the president on his re-election. The letter, written in faltering English, is clearly in the language of a boy and, now preserved in US government archives, is a fascinating relic of the twentieth century. The letter was written in November 1940.

The most amusing part of the short letter is the young Castro offering the American President access to his country’s iron for use in constructing American ships. The child-like offer appears at the end of the letter, in a kind of ‘PS’; ‘If you want iron to make your ships,’ he wrote, ‘I will show to you the bigest (minas) of iron of the land. They are in Mayari Oriente Cuba.’

President Roosevelt apparently didn’t respond to the letter; and he may not have ever even seen it. And whoever did originally see that letter from the random Cuban boy obviously had no conception of who that boy would grow up to be and how it would, at one point, bring America to the brink of destruction in its conflict with the Soviet Union.

Highlighting all the highly significant letters that have passed into the public domain would be too long, as there’s so much to consider, but the nature of these letters ranges from the political, such as fascinating war-time correspondence, to the highly personal, such as correspondence between friends or between romantic interests; and from the infamous, such as the notorious Jack the Ripper letters or some of Hitler’s early correspondence, to the more endearing in nature, such as a letter I recently came across on a website that Henry VIII wrote to Anne Boleyn.

Addressed “To My Mistress” and concluded “Written by the hand of your entire Servant”, the letter goes on to speak of their being apart and how much he misses her. “Consider well, my mistress, that absence from you grieves me sorely.” Our knowledge of the nature and fate of their relationship makes it all the more bittersweet reading.

Letters from eras we are remote from can be the most poignant because we have the historical hindsight with which to read all kinds of ironies or foreshadowing into the sentiments that wouldn’t have been deliberate at the point of writing.

The degree of insight into important historical figures that is provided by surviving letters cannot be understated.

Thinking again of that letter from Henry VIII to the ill-fated Anne Boleyn, ‘Love letters’ are also a classic motif now mostly consigned to the past, and somehow text-flirting or relationship updates on Facebook don’t have anything like the same aura of sentiment to them.

As fascinating as items like the Gandhi letter to Hitler are, going even further back in history provides even more extraordinary windows into lives and worlds long gone.

It’s remarkable how much written correspondence survives from the ancient world. This includes items as old as Egyptian letters preserved in ancient papyri or carved correspondence in even more ancient Babylonian or Mesopotamian clay tablets.

Possibly the most famous collection of letters in Western culture are the Letters of Saint Paul, written over a number of years in the 1st Century AD. These letters are essentially the basis of Western Christianity and therefore of centuries of Western civilisation.

They are also a fascinating insight into the theological foundations of Christianity and into Paul of Tarsus as a personality. Much of the New Testament, in fact, is made up of letters written to early congregations or communities or between figures of the early Christian movement: and are therefore a fascinating insight into early Christianity and into the first century Mediterranean world.

Letters salvaged from the ravages of time serve immeasurable value as historic documents, particularly in regard to classical eras. Surviving letters, for example, written by such famous figures in the Roman world as Ovid, Seneca and Pliny the Younger, provide an extraordinary level of insight into not only those specific historical figures but also the events and the times they lived in.

And of all these the most fascinating is Marcus Tullius Cicero. Cicero’s letters are one of the most crucial resources for understanding of that extraordinary period in Roman history, essentially the end years of the Roman Republic. They give us invaluable insights into the workings of the great orator’s mind and indeed the minds of his friends and contemporaries; as they were essentially private correspondence not intended for circulation they are unencumbered by the kind of eloquent rhetoric Cicero was famous for in his political speeches.

It is the gift of posterity that Cicero was such a prolific writer of letters; his correspondence includes everything from the statesman’s thoughts about Caesar, the Civil Wars, the Republic, Octavian, Mark Antony, and myriad other matters. In addition to the classic collections of Cicero’s speeches, there are Penguin editions of Cicero’s letters to Atticus, Brutus and the second volume which Penguin entitled ‘To his Friends’.

The letters to Brutus are especially fascinating, as reading them you can feel the tension and urgency; of course, reading two-thousand years later, for us the letters are framed in the knowledge that Cicero and Brutus were both heading towards their deaths and that the Republic would be lost and the Empire born despite their efforts.

“Believe me, Brutus, you and your friends will be crushed if you do not take care. You will not always have a people and a Senate and a leader of the Senate as they are today. You may regard these words as a Delphic oracle. Nothing can be more true.”

Those words were part of a Cicero letter to Marcus Junius Brutus, concerning Mark Antony, who Cicero believes Brutus should’ve had killed while there was still time. Brutus was too principled and noble to have Antony killed, but it proved to be his future undoing. This letter was written in 43BC, a year before Brutus’s death in the Battle of Phillipi.

But it’s not just the stars of the ancient world that survive through their letters; in fact, more often than not it’s not the great historical personages at all, but the little people that come to life again millennia after their existences.

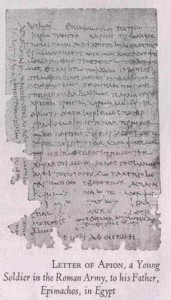

For example, here is an example of a real letter from a Roman soldier. Written in the 2nd Century AD by a young man named Apion serving in Egypt, it is a simple letter back home to his father and contains the kind of language and references we could expect from any young man’s simple letter back home today, the mundanity of the message being part of its charm.

Handwritten letters are also an invaluable insight not just into historical figures or events, but also into more modern pop-cultural figures and icons.

Among the more famous examples, a number of Marylin Monroe’s letters have become a much-read series of insights into her inner nature and feelings, while Elizabeth Taylor kept a trove of around forty letters written to her by Richard Burton during the various stages of their marriages and divorces. The letters were in fact the basis for a dual Taylor/Burton biography about their famous love life.

Something that I’ve always found quite moving was a letter Orson Welles wrote to Rita Hayworth during the earlier days of their relationship (another love affair doomed to failure).

“I suppose most of us are lonely in this big world,” Welles wrote to Hayworth, “but we must fall tremendously in love to find it out. The pleasures of human experience are emptied away without that companionship now that I’ve known it; without it joy is just an unendurable as sorrow.”

There’s more to Welles’s letter, but you get the gist.

There are even more modern cult figures or figures of cultural significance whose letters once put into the public domain become part of the perception of their overall image. Whether Kurt Cobain’s journals were ever meant to be seen or not is debatable, but they’ve been published in book form for some years now and include a number of letters he wrote, some of which were probably never sent, including scathing letters to MTV and elements of the press, at least one particularly poignant letter to Courtney Love that I recall, and very early letters from Nirvana’s inception.

The book begins with a scattered letter Cobain wrote to Melvins drummer Dale Crover in 1988, discussing various subjects including the disease of late-night television, the superficiality of publicity, and the decision to name his band Nirvana. While it lacks cohesion and while I wonder about whether letters of this type belong in the public domain (or whether he would’ve wanted them to be), it is undeniably very interesting to look at someone like Kurt’s little letters and doodlings, all in his own messy handwriting.

They do provide a degree of insight.

Just from this small sampling of significant letters touched upon in this articles and from different times and walks of life, and penned by vastly diverse hands, we can see how important an element of our collective culture and history they form; and these are just a few good examples among too many to keep count of.

They are a treasure-trove. But the problem, moving forward from this time, is that it’s possible no such treasure-trove or sources of insight will exist in terms of contemporary life and how it is perceived or preserved for future generations.

Are emails, Facebook posts or tweets going to be preserved or examined in the distant future? Will future people be studying politicians’ or celebrities’ Twitter timelines the same way we currently might study the letters of T.E Lawrence or Orson Welles or Gandhi? Can Facebook timelines or email texts hold the same mystique or reverence?

And what if, some day, something causes the Internet to be wiped out – and all that ‘data’ is lost anyway?

Whether handwritten letters will survive as a practise into the future of course depends entirely on whether we in general retain any desire to keep such acts alive in our own lives and to put pen to paper to express whatever it is we’re trying to express to whoever it may be we’re trying to express it to.

But to quote a famous lover of letters, the writer Virginia Woolf; “Venerable are letters; infinitely brave, forlorn, and lost.”