There is something innately fascinating about, not so much the judicial process as a whole, but the institution of the trial itself.

That’s why court-room dramas are so popular. From classic films like To Kill a Mockingbird, 12 Angry Men or even the trial of Kirk and McCoy in Star Trek: The Undiscovered Country, to historical accounts such as the trial of Calpurnius Piso or Copernicus, the court-room battlefield remains one of the most engaging, particularly in regard to high-profile or historic cases.

We also tend to wonder about the ‘what ifs’ of history; trials that famously never happened for whatever reason. Examples of that would be the trial of Adolf Hitler; we can only wonder what would’ve been said or argued had the Fuhrer himself been made to stand trial along with the likes of Goering and Eichmann. Saddam Hussein made a significant show of his trial in 2005; we can only imagine Hitler would’ve done the same. And what would someone as engaging as the late Muammar Gaddafi have made of his trial, had he been afforded one and not instead been unlawfully murdered?

Perhaps the most famous non-trial of modern history would be Lee Harvey Oswald; the “patsy” accused by the establishment of assassinating an American President was himself unlawfully executed while in police custody so that he could never speak publicly. The killing of Lee Harvey Oswald in fact was so extraordinary a conspiracy (particularly for its brazenness) that it has inspired more than one fictional ‘Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald’ over the years. Actually a fantastic historical resource is the film researcher/author Mark Lane made in 1967; Rush to Judgement. Someone has thankfully uploaded the film in its entirety on You Tube – anyone who’s never seen it should do so; it is fascinating not just as conspiracy/truth research but also as a historical item, given how soon after the JFK assassination it was made.

But let’s get back to the initial theme; from Jesus of Nazareth to Herman Goering, here are 10 famous trials that remain permanently fascinating for different reasons…

The Salem Witch Trials

The infamous Salem witch trials began during the spring of 1692, after a group of young girls in Salem Village, Massachusetts, claimed to be possessed by the devil and accused several local women of witchcraft. A wave of hysteria then plagued colonial Massachusetts and a special court convened in Salem to hear the cases.

The first convicted “witch”, an unfortunate woman named Bridget Bishop, was hanged that June. No less than eighteen others were executed at Salem’s Gallows Hill, while somewhere in the region of 150 more men, women and children were accused over the next several months. However, by September of that year the hysteria had begun to abate and public opinion began to reverse, turning against the trials.

Though the Massachusetts General Court later annulled guilty verdicts against accused “witches” and granted reparations to the families of those executed, bitterness lingered in the community over the insanity that had blackened its name.

Medieval belief in witchcraft, along with belief in the supernatural and in the devil as an active presence in daily life was carried to America by its European immigrant colonists and became widespread in colonial New England. Additionally the harshness of life in a Puritanical community lends itself to mistrust, fear and informing against neighbours, as well a suspiciousness towards outsiders (picture the archetypal flaming torch and pitchfork-wielding angry village mob); all of this, among other influences, may have acted as a cause for the Salem hysteria.

The controversial (and more than anything embarrassing) legacy of the Salem witch trials has endured well into modern times, permeating both popular culture and modern literature. Arthur Miller dramatized those in his 1953 play The Crucible, which later also spawned a film starring Winona Ryder.

Salem is essentially now a by-word for any kind of unjust ‘witch-hunt’ or persecution, and the entire grim episode can be regarded as a potent demonstration of social contagion and the nature (and power) of hysteria.

Indeed Miller’s play was written an allegory for American McCarthyism, which was rampant at the time. While most Americans would regard the Salem Witch Trials as merely a bleak historical item, we still have societies on earth that could be said to be subject to the same kind of shared hysteria and social contagion; specifically either primitive cultures or less primitive cultures but where religious fervor is still rampant and where things like stoning adulterers, genital mutilations honour killings go on.

Even something as enormous as Nazism in Germany might be regarded as social contagion on a massive scale (or to some extent, the spread of the fanatical ‘Islamic State’ cult today).

Adolf Eichmann

Captured by ‘Nazi Hunters’ in Argentina some years after the collapse of the Third Reich and the end of World War II, Adolf Eichmann was forcibly taken to Israel to stand trial for his role in the Holocaust.

He was subjected to daily interrogations, the transcripts of which are said to total 3,500 pages. It was noted by the Chief Inspector Avner Less that Eichmann ‘did not seem to realise the enormity of his crimes’ and showed no remorse for his part in the Final Solution.

Eichmann’s trial before the Jerusalem District Court began on 11th April 1961. He was indicted on 15 criminal charges, including Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes, “Crimes Against the Jewish People”, and membership in a criminal organisation. The government of the then newly created State of Israel arranged for the trial to have prominent media coverage. Major newspapers from all over the world sent its reporters and published front-page coverage of the story. At the Beit Ha’am in central Jerusalem, Eichmann sat inside a bulletproof glass booth to protect him from assassination attempts. The building was modified to allow journalists to watch the trial on closed-circuit television and 750 seats were available in the auditorium itself.

–

–

Israelis had the opportunity to watch live television broadcasts of the proceedings and film was flown daily to the United States for broadcast the following day. Many decades before Oscar Pistorius or OJ Simpson, Eichmann’s case can be said to have been the first mass media trial. The prosecution case was presented over the course of 56 days, involving hundreds of documents and 112 witnesses, many of them Holocaust survivors. The court’s stated intention was to not only demonstrate Eichmann’s guilt but to present material about the entire Holocaust, thus producing a comprehensive record.

Throughout his cross-examination, prosecutor Hausner attempted to get Eichmann to admit he was personally guilty, but no such confession was forthcoming. Eichmann admitted to not liking the Jews and viewing them as enemies, but stated that he never thought their annihilation was justified.

The verdict was read on 12th December. The judges declared him not guilty of personally killing anyone and not guilty of overseeing and controlling the activities of the Einsatzgruppen. He was, however, deemed responsible for the dreadful conditions on board the deportation trains and for obtaining Jews to fill those trains. He was found guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes against Poles, Slovenes and Gypsies. He was also found guilty of membership in organisations that had been deemed criminal at the Nuremberg trials.

The judges concluded that Eichmann had not merely been following orders, but believed in the Nazi cause and had been a key perpetrator of the genocide. On 15th December 1961, Eichmann was sentenced to death.

There are some aspects of the Eichmann trial, even looking at it now, that remain uncomfortable.

One of the them involves the terms of some of the charges, this being an issue some take with the Nuremberg Trials too; for example, ‘membership of a criminal organisation’ is so broad and yet vague a charge that there are surely all kinds of people who could’ve been put to death on those grounds. Further to that, Hausner’s stated intent for the trial to act as a ‘comprehensive record’ of the Holocaust seems to undermine the validity of the process, which was after all supposed to be about Eichmann specifically.

Making the trial about the Holocaust in broader terms always risked making it an exercise in mass emotiveness and was hardly fair to Eichmann himself, who thus ended up – in effect – standing trial for the entire Nazi regime.

To some observers, the entire affair was more like a collective catharsis for the Israeli people or a mass/collective sense of justice being enacted upon one individual for the mass crimes of the many individuals and forces that constituted the Third Reich.

Some observers also questioned the legitimacy of someone being kidnapped from a foreign country – Argentina – and forcibly taken to Israel instead of standing trial in Germany or in Europe where the crimes he was accused of had taken place.

In fact one of the contemporary figures who had misgivings about Eichmann’s trial was the writer, philosopher and Holocaust survivor, Hannah Arent. Arendt, herself Jewish (and later considered one of the great minds of the 20th century), was concerned that the trial was being used for nationalistic propaganda purposes and to inflame popular feeling, rather than being a fair or sober process.

Whatever the legitimacy of the process, the Trial of Adolf Eichmann nevertheless did act as a record, an exhibition, of the worst mass crime of the twentieth century.

The Trial of Clay Shaw

Made even more famous by Oliver Stone’s earth-shattering JFK film, Shaw remains to this very day the only person ever brought to trial in regard to the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

On 1st March, 1967, New Orleans District-Attorney Jim Garrison arrested and charged popular New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw with conspiring to assassinate President Kennedy, with the help of Lee Harvey Oswald, David Ferrie and others.

On January 29th 1969 Shaw was brought to trial in Orleans Parish Criminal Court on these charges. The jury took less than an hour to find Shaw not guilty. Garrison’s case centered around witness Perry Russo who testified that he had been at a party in which Shaw, David Ferrie and others (with Lee Harvey Oswald present) had discussed the killing of the President, including alibis and the famous “triangulation of crossfire” that was a key feature in both Garisson’s book On the Trail of the Assassins and the Oliver Stone movie that was based on it.

Critics called into question the legitimacy of Garrisson’s case and the reliability of witnesses; however, the fact is that the entire process was made extremely difficult for Garrisson, who was fighting an uphill struggle all the way, including ‘missing witnesses’ that would’ve been key to his case. Russo has in several later public interviews maintained his account of the “assassination party”.

In a 1992 interview, Edward Haggerty, the judge at the Shaw trial, said, “I believe he was lying to the jury. I think Shaw put a good con job on the jury.”

In On the Trail of the Assassins, Garrison declares that Shaw had an “extensive international role as an employee of the CIA.” Mr Shaw denied having any connection with the CIA. In 1979, Richard Helms, former director of the CIA, testified under oath that Clay Shaw had been a part-time contact of the Domestic Contact Service of the CIA.

Garrison came to believe, as many researchers do, that the CIA was involved in the assassination of the President.

While many mainstream commentators in the US heavily attacked Garrison’s campaign and the treatment of Clay Shaw, this prolonged smear campaign against the New Orleans District Attorney was in part an unwillingness to depart from the collective fantasy of the official verdict (reached by the Warren Commission) and may also have been in part a concerted programme by official agencies to thwart both Garrison in particular and inquiry into the assassination in general.

Over fifty years now after the fact, however, the body of evidence to suggest that the CIA (among other parties) was involved in the assassination of JFK and that Lee Harvey Oswald was at best a patsy (or, according to Garrison himself, not even one of the assassins) is overwhelming.

And though Garrison himself is still seen as a divisive figure, it is difficult to view him as anything other than a true American patriot of noble intent and one of the few genuinely ‘heroic’ figures in the entire sordid arena of the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath.

Saddam Hussein

The capture of Saddam Hussein several months after the illegal invasion of Iraq by US-led coalition forces was one of the most compulsive news events in modern times. But his subsequent trial was even more so.

On July 1st 2004, Saddam was arraigned before a judge and was charged with war crimes and genocide. The proceedings were mired in controversy. During the long, drawn-out course of the trial one of Saddam’s defense attorneys was kidnapped and murdered. But the most compulsive element of the trial was Saddam himself, who used the platform to speak and argue, sometimes zealously, sometimes eloquently.

It became, perversely, his final performance stage in the world. The video clip here is just a taste of what Saddam had to say.

–

–

On December 7th 2005 Saddam refused to even enter the court room; the night before that he’d told the tribunal to “go to hell”. The case continued without the defendant even being present. At the end of that month, Saddam’s chief lawyer sent a letter to President Bush advising that if America wanted to end its problems in Iraq then Saddam should be freed (I imagine this was laughed at at the time, but a decade later and with Iraq in far worse condition than it had been under Saddam, it now seems more than a little prophetic).

Just under a year later in November 2006 the former dictator was sentenced to death by hanging. Saddam’s appeal was rejected and on New Year’s Eve 2006 Saddam Hussein was hanged.

I suppose we could say at least he got a trial and one last platform; which was more than Gadaffi got in Libya. But most observers, including multiple journalists covering the event, couldn’t pretend that the former Iraqi dictator had been given a fair trial.

Jesus of Nazareth

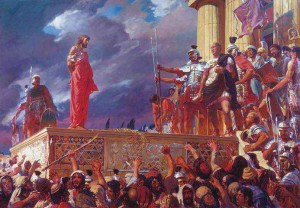

The trial of Jesus, as recorded in the Gospels, is probably the most famous in history.

Whether it happened that way or not is beyond the business of this article; but from his capture in the Garden of Gethsemene and his silent appearance before Herod Antipas to his questioning by the Jewish Sanhedrin and appearance before Roman Governor Pontius Pilate, the power of the story, as with Joan of Arc, is of an essentially innocent individual being delivered into the hands of his enemies for torture, humiliation and eventual execution.

Religious or not, the imagery of Christ wearing the crown of thorns, being marched down the Via Dolorosa and bearing his own cross, and eventually dying at Golgotha in full view of his people has resonated endlessly down the centuries, the subject of famous paintings, films, religious devotion, even intense stigmata.

That imagery, its emotiveness, and all its intense religious themes, are an indelible part of our collective consciousness, even in secular societies.

Modern re-assessments (some scholarly, some purely speculative) of the Gospel narrative have provided even more fascinating, though less powerful, takes on what might really have been going on in 1st century Palestine; including theories that Jesus was a Jewish Zealot and not as innocent as the tradition suggests, theories that he didn’t die on the cross, and theories that the ‘Resurrection’ was a master-hoax pulled off by some of his followers with the help of the Romans.

Some of these ideas, the subject of numerous books, are utterly fascinating and thoroughly worth reading (Bloodline of the Holy Grail by Lawrence Gardner and Jesus of the Apocalypse by Barbara Thierring, both published around twenty years ago, are two very good examples).

However, even taking the traditional interpretations at face value, the historic characters, forces and motivations involved in the prosecution have always made for a highly engaging equation; from the Jewish priests and their rejection of the “false prophet”, to the pragmatic Roman Procurator, Pontius Pilate, struggling to make any sense of Jewish religious concerns, even to Jesus himself and his resigned silence when being questioned.

Even the reasons for Jesus being arrested are questionable or debatable. In some arguments, he is accused of sedition and of inciting rebellion against the Romans. On the other hand, the Jewish priesthood objected to him being seen as the Messiah. Other arguments are that he blasphemed by citing himself as the Son of God (though it’s arguable whether he actually made that claim of himself – the term ‘Son of Man’ is the one that the Gospel writers have him saying).

Whatever actually happened in reality, the potency of the story and power of the imagery is endless in its effect and influence on our collective cultural consciousness.

Joan of Arc

On May 30th 1431, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake at the Old Marketplace in the medieval town of Rouen; that horrific death ensured her cultural immortalisation for all ages.

Hers remains one of the most enduring medieval legends and probably the one most revisited in film and fiction over the centuries. Only Robin Hood could match the legend of Joan of Arc for both longevity and popularity; though Joan’s story, unlike Robin’s, is pure historical fact.

The legendary French peasant girl turned war hero had been captured by the English in 1431 at the age of 19 and was tried for heresy. One of the remarkable things about the end of Joan’s brief life is the extent of documentary evidence from her trials that survived, allowing posterity a privileged amount of insight. It is generally felt by history that she was the victim of a conspiracy by the English, the church and by the Burgundians and other French factions loyal to England.

Some historians also believe some of her own people, including the French Dauphin Charles VII who owed his own crown to Joan’s devotion and her actions, had essentially sold her out to her enemies, rendering the legendary ‘Maid of Orleans’ a Lee Harvey Oswald like ‘patsy’. She was sacrificed for political convenience.

Very little about the trial was ever going to work in Joan’s favour: it was conducted before a jury of generally sexist ecclesiastics who were wholly hostile towards her. Pro-French clerics who might’ve had both the desire and the authority to speak in her defense were not allowed to participate. Declared guilty and sentenced to lifelong imprisonment, once imprisoned she resumed her habit of wearing male clothing, this time to avoid being molested by English guards (having already been raped on several occasions).

This gender-inappropriate behaviour provided the authorities with the justification they needed to execute her as a “relapsed heretic”.

The records of her trial are a fascinating historical resource. One of the main facets of Joan’s legend of course were the ‘voices’ she’d always claimed to have been guided by; most historians of course now ascribe this part of the legend to a psychological disorder or a form of multiple personality syndrome, though those who believed in her at the time believed she was in communion with the spirits of saints and was guided by God.

In one of the earliest sessions of her trial, dated Wednesday February 21st 1431, she was asked about her ‘voices’ and is recorded as having answered, “Concerning my revelations from God, these I have never told or revealed to anyone, save only to Charles, my King. And I will not reveal them to save my head.”

It took another 25 years after her burning at the stake for the farcical verdict to be overturned by the church, the extraordinary injustice of the trial acknowledged. Five centuries later, Joan of Arc was canonized as a saint. The enduring power and popularity of Joan’s story is unsurprising, given her youth and naivety, courage and extraordinary battlefield accomplishments, and of course her horrific and unjust death at the hands of corrupt, cruel men and farcical religious authorities.

As she was slowly enveloped head to toe in flames, I wonder if she thought even for a moment that she might end up as the patron saint of the entire country; or that historians, filmmakers and church authorities would still be talking about her centuries later.

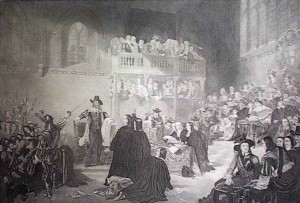

Parliament Versus Charles I

One of the most famous, and to some most traumatic, events in English history; the public beheading of a King of England before his subjects. “The blow I saw given… I remember well,” said a historic witness to the regicide in 1649, “there was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again.”

Charles I, once King of Great Britain and Ireland, was forced to stand trial in 1649 by Oliver Cromwell and the Parliamentarians for his perceived abuses of his regal powers. The decade prior to that the King had been at war with Cromwell and the men who were now bringing him to trial. Having lost the English Civil War, Charles refused to cooperate with Parliament’s demands for a constitutional monarchy, and was generally accused of using his powers to further his personal interests rather than the good of the country.

A revolutionary tribunal was created specifically for the purpose of prosecuting the monarch.

A man who has been described as “the most incompetent monarch of England”, yet clearly one of the most charismatic figures of British history, views of Charles I have been varied and divisive; modern historians generally seem to take a negative view of his kingship, though to some for many years after his death he was seen as a martyr, even a saint.

What’s clear is that he was utterly unwilling to adapt and he deliberately pursued unpopular policies that were always likely to bring ruin upon himself.

Like Saddam Hussein or Herman Goering centuries later, the deposed King regarded the entire affair with haughtiness, refusing to acknowledge its legitimacy; which no doubt only enraged his prosecutors further. When given the opportunity to speak, Charles refused to enter a plea, claiming that no court had jurisdiction over a monarch. He believed that his own authority to rule had been by “Divine Right of Kings” given to him by God.

“I would know by what power I am called hither,” the ill-fated King is quoted as having said during the trial. “I would know by what authority…”

Parliament declared that Charles was a traitor and a tyrant; the King was declared guilty at a public session on 27th January 1649 and sentenced to death. The head of Charles I was severed in front of the banqueting hall of his own palace, witnessed by a crowd of thousands. The monarchy was abolished. But only for a time; the republican Commonwealth of England (and later Protectorate of Cromwell) barely lasted a decade before monarchy was restored to the dead king’s son, Charles II.

The Westminster trial itself, however, would be one of the most fascinating historical events to go back and witness, were it possible; not just for its high stakes and grim outcome, but because it essentially featured two of the most fascinating figures in British history – Charles I and Oliver Cromwell – engaged essentially in a battle to the death.

A curious side-note: it is persuasively argued that the legendary French prophet Nostradamus, writing a century or so before these events, foretold the execution of Charles I in one of his quatrains and did so in a tone that portrayed it as a monstrous crime. The pro-monarchist occult diviner attributed the Fire of London, which occurred a few years after the regicide, as a divine punishment for the death of the king.

The subject of countless books, studies and re-imaginings, the relationship between Cromwell and Charles I was also immortalised in the film Cromwell, starring Richard Harris and Alec Guinness; the result of which is that I can’t think of Charles I anymore without seeing Alec Guinness.

The Nuremberg Trials and “The banality of evil”

The most famous trial(s) of ‘modern’ times. Twelve trials, involving over a hundred defendants, took place in Nuremberg from 1945 to 1949. It has been said that no process in history has provided a better platform for understanding the nature and causes of evil than the Nuremberg trials.

But those who approached the tribunals expecting some sort of ‘satisfaction’ of witnessing cold and sadistic monsters being brought to justice would’ve been disappointed. In some ways what was considered most remarkable about the whole thing was the sheer ordinariness of the defendants; observers were forced to confront the juxtaposition of seeing men accused of unspeakable evil appearing instead as banal, innocuous types; men who could easily be envisioned as fathers, husbands, pet owners, etc.

Years later, when Hannah Arendt reported on the the trial of Adolf Eichmann is Israel, she spoke famously of “the banality of evil.”

What emerged was not the image of evil, scheming, Red Skull type villains, but more a case of men over-identifying with a virulent ideological cause. Or pragmatic men so bound up in the sheer career-motivated bureaucracy of what they were involved in that they failed to properly register the vast human consequences of the policies they were helping carry out.

It was evident too, however, that some of the men were even at that time still under the ‘spell’ of the Fuhrer and would speak his praises all the way to the gallows.

The most attention was focused on the first trial (the Major War Criminals Trial) of the twenty-one ‘major’ war criminals; including the more famous Nazi figures such as Herman Goerring and Rudolph Hess (both pictured next to each other above, farthest left). Goering turned out to be the ‘star’ of the show; even some of those involved in the prosecution later remarked on Goering’s charisma and even his almost endearing nature throughout the process.

Some of the defendants did offer apologies. Some shed tears. Goering, with an attitude that would be echoed somewhat by Saddam Hussein sixty years later, told the court that the entire trial was nothing more than an exercise of power by the victors of war. Justice, he said, had nothing to do with it.

Meanwhile Rudolf Hess offered an odd, intriguing final statement, filled with references to visitors with “strange” and “glassy” eyes (conspiracy theorists take note).

Albert Speer used the platform to offer a warning. He spoke of the even more destructive weapons then being produced (a reference to atomic bombs) and the need to eliminate war once and for all. “May God protect Germany and the culture of the West,” Speer said, referring to the rise of Communism that accompanied the end of Nazism.

Away from the major tribunal, some of the eleven later trials addressed even more disturbing issues; the trial of sixteen German judges and officials of the Reich Ministry (The Justice Trial) considered the criminal responsibility of judges who enforce immoral laws. That particular trial was the basis for the Judgment at Nuremberg movie featuring Judy Garland. Other subsequent trials, such as the Doctors Trial and the Einsatzgruppen Trial, were especially compelling due to the horrific events described by the witnesses.

The ‘star’ of the show, Herman Goering, escaped the indignity of execution, taking his own life instead. On October 15th, the day before the scheduled executions, he wrote a note to the “Allied Control Council”, saying “I would have had no objection to being shot. However, I will not facilitate execution of Germany’s Reichsmarschall by hanging!” He concluded,“I have chosen to die like the great Hannibal.”

The Nuremberg trials still provoke heated discussion. Questions are still raised both about the legitimacy of both the tribunals and the verdicts that were reached. To some the definitions of ‘war crimes’ were so all-encompassing that virtually anyone involved in the war could’ve been charged along those lines (including British, American and Soviet personnel); consequently, although the tribunals did bring the depth of Nazi crimes to wide public knowledge (and documented Nazi atrocities for all posterity), they have also served the unintended purpose of creating some degree of sympathy for some of the defendants over time.

All of that said, however, the Nuremberg trials might legitimately be seen as a necessity in showing not just the world, but the population of Germany specifically, the worst of what had been going on under Nazism; to ensure that the people of Germany did not fall into the mentality of denying the reality of what had happened or regarding Hitler, Goering and the rest of the Nazi regime as martyrs.

It has to be remembered that the majority of people, including most ordinary German citizens, were not aware of the extent of what had been going on or of the scale of the Jewish exterminations in Europe: and that it could be argued that one of the purposes of the trials were to make this reality clear.

Most historians regard the Nuremberg tribunals as having contributed massively to the subsequent democratisation of Germany. However, defendant Albert Speer’s remark that “This trial must contribute to the prevention of wars in the future,” hasn’t be borne out by subsequent history.

In fact at this precise moment in international affairs, more than any other since the Nuremberg trials took place, it is evident that ‘peace’ isn’t something we’re likely to attain for a very long time yet and that “war crimes” are no thing of the past.

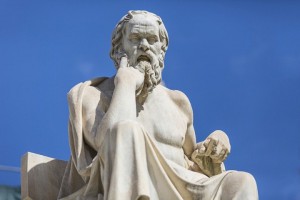

Socrates: The Trial of a “Curious Person”

“If you think that by killing men you can avoid the accuser censoring your lives, you are mistaken. That is not a way of escape which is either possible or honorable,” said Socrates. “The easiest and the noblest way is not to be crushing others, but to be improving yourselves.”

Socrates, that most famous of the Greek philosophers, was put to death by his fellow Athenian citizens in 399 BC, officially charged with “impiety” and “the corruption of the Athenian youth”. He was said to be “an evil-doer and curious person, searching into things under the earth and above the heaven.”

What all of that meant, in essence, was that he’d become annoying (as comedically illustrated by the brilliant Eddie Izzard in a stand-up sketch). He had a tendency to point out people’s ethical mistakes and to overly question everything he could; to be fair, he was a philosopher and that was his business. And we’ve all got a friend like that, haven’t we?

At the trial, Socrates, like Goering and Saddam centuries later, gave a powerful speech in his own defense. “Unlike other men,” he is reported by history to have said, “I do not know how to be eloquent. All I know how to do is to speak the truth; and that is all I have ever tried to do; and that is what I will now proceed to do.”

Greek historians tell us that he proceeded to defend himself beautifully, but was eventually found guilty by a majority of votes.

After receiving his verdict of forced suicide, Socrates left the court-room, saying: “The hour of departure has arrived, and we go our ways – I to die, and you to live. Which is better, only God knows.”

He was taken to prison and forced to drink hemlock. Surrounded by his friends, he spent his final moments fittingly engaged in discourse concerning the immortality of the soul; thus dying a true philosopher’s death.

Thomas More

It remains one of the great tragic stories of English history; the tale of how one of the most revered men in England, Sir Thomas More, ended up on the chopping block of Tower Hill in 1535.

But it’s also a tale of dignity and integrity in the face of death, with More confronting both his trial and execution in calm, pious fashion.

In 1533 Thomas More, Henry VIII’s friend and one time Lord Chancellor, refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as the Queen of England. Strictly speaking this itself was not a treasonous act, as More had written to Henry acknowledging Anne’s legitimacy as queen and expressing his desire for the King’s happiness and the new Queen’s health. Despite this, his refusal to attend was widely interpreted as a snub against Anne (and an expression of More’s refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy of Henry’s divorce from Catherine of Aragorn) and Henry took action against him.

More refused to take the ‘oath of supremacy of the Crown’ which was being forced upon essentially everyone at the time; the oath sought to re-define the relationship between the crown and the church in England. Henry had his friend More imprisoned in the Tower of London. It was while in the tower that More prepared his devotional Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation.

While More was imprisoned, Thomas Cromwell made several visits, urging the renowned social philosopher to take the oath, which More continued to refuse on principle.

Cromwell ironically would end up minus his own head soon enough too, as of course would Anne Boleyn (the number of decapitations being carried out on the King’s orders, Henry VIII would probably be at home as an Islamic State militant).

In July 1535, More was tried before a panel of judges that included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, as well as Anne Boleyn’s father, brother and uncle. He was charged with “high treason” for denying the validity of the Act of Supremacy. More followed in the footsteps of Jesus somewhat (unsurprising given his deep religious convictions) by being silent when questioned on the subject; he believed that he could not be convicted as long as he did not explicitly deny the King was Supreme Head of the Church.

Which, as far as history is able to record, he never did.

The evidence that was brought against him – claims by third parties that More had privately condemned the King’s position – amounted to mere hearsay and was highly dubious.

More was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered; but on account of More’s reputation and presumably of their past friendship the King commuted this to execution by decapitation. The execution took place on 6th July 1535. Although views of Thomas More (later canonised by Rome) vary depending on political or religious dispositions, the story is generally regarded as one of a deeply principled individual holding steadfastly to those principles even when he had every opportunity (and reason) to save his own life.

It is also seen as the story of a vain-glorious King of England and his excessive sexual appetite (his lust for Anne Boleyn), as contrasted to the seemingly pious, morally upright More who, even at his place of execution, remained sober, thoughtful and forgiving.

More’s best known and most controversial work, Utopia, was written in Latin and was only translated into English many years after his death (in 1551), and is cited as a major influence on what would become a substantial literary genre; that of Utopian or dystopian fiction, which centers on ideal societies or perfect cities or societies (or their opposite).

What was a Renaissance genre carried on into the Age of Enlightenment, but subsequently found its most enduring home in the realms of modern science fiction.

________________________