So. The crucifixion. And the resurrection.

A story, a myth, or an ideal or a foundation-stone of faith, that has exerted an almost unparalleled power over generations, societies, and millions and millions of people for almost two-thousand years.

Did it happen? No one knows. No one will ever know.

Even if it did happen, what exactly happened? What did people think had happened? And what did other people want to think had happened? And what did other people want US to think had happened? And why?

If you ask people of faith about the crucifixion/resurrection story, the answer will be – as it has been for many hundreds of years – that a Divine Son of God was executed on a cross, died for the sins of future believing Christians (as a kind of final, ultimate human sacrifice or ritual sacrifice), and rose back to life again two days later.

If you ask non-religious people about the crucifixion/resurrection story, most will probably say it was all a myth that got out of hand, while some will also say the whole thing was a cynical creation invented (and back-dated) long after the time in question.

Most people would look only at those two opposing vantage-points: and would assume that either one or the other was the truth.

But what if neither of those is the truth?

What if the reality actually lay somewhere in the middle of the two, as odd and contradictory as that sounds?

So here’s what’s at the heart of the big ‘Easter’ conspiracy then: what if Jesus was crucified, did appear to die and did appear to rise from death?

What if – removing all of the later baggage and religious dogma and mythology from the equation – there actually was a *version* of that Gospel narrative that really did play out in real-time and in real life?

But what if most of it was sleight-of-hand and perception-management: a conspiracy played out to fool people?

That possibility has been in the mix for some time now, forwarded by several authors: that the crucifixion/resurrection narrative was actually a ‘passover plot’ involving various key figures and facillitated by the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate.

You could call this a 1st century conspiracy-theory masterclass, in which the Roman Governor conspired with other key figures to pull off a grand illusion: and from which the unforeseen result was the emergence of Christianity itself.

And that’s what I want to explore in this article: because it’s a theory that has fascinated me for many years now. Regardless of whether it’s the truth or not, the theory itself is arguably more interesting than even the religious version of the story (though, admittedly, much less ‘inspirational’ in the religious sense).

But before coming to that, let’s just establish some background on Pontius Pilate: because doing so helps illustrate the disparities that have always existed between real historical figures and their fictional or mythologised counterparts that appear in venerated texts. That dynamic doesn’t just apply to Christian scripture but to all religious texts and traditions and indeed almost all ancient literature.

Pilate’s story is an odd one, but is illustrative of the fact that history – especially religious ‘history’ – is largely unreliable, because it was usually not constructed with fact or objectivity in mind, but was rather a carefully-woven tapestry of spiritual ideas, mythology, propaganda and allegory designed to support emerging systems of belief (albeit with some ‘real’ history included in the narrative bedrock).

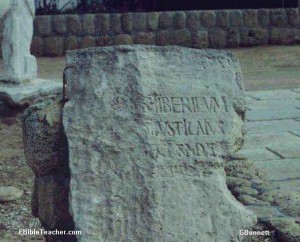

There are few historic references to Pontius Pilate: but enough to demonstrate that he was a real historic figure and was Governor in Judea during the reign of Tiberius. But that’s about it. The problem is that Pilate is, in the broader context of Roman history and the 1st century world, a nobody. That’s also why there are no solid references to the historical Jesus from non-Christian sources: in Roman terms, the whole affair really was a minor side-show that didn’t become significant until a lot later – by which time, a lot of the tradition was being retro-fitted to suit an emerging mythology that was being constructed.

I don’t want to get into the argument of whether Jesus really existed or not as a historical figure. There are reasonable arguments on both sides of that question: my personal view has always been that a historical Jesus probably did exist, but that his story – and very nature – became so warped and mangled in the three centuries or so after his lifetime that there’s no way of ever truly recovering the historical figure from the centuries of accumulated mythology and baggage.

Though I also acknowledge the case made by various historians for Jesus Christ having been a fictional, archetypal character transposed onto a historical setting by 1st century writers trying to establish a new spiritual tradition.

However, this is such a wide-ranging subject with so many different angles, considerations and theories that I’m not even going to attempt working through it here. And I don’t have a definite opinion anyway: I’m basically a non-religious but open-minded type, with no particular investment in any fixed interpretation or conclusion.

And, in looking at the figure of Pontius Pilate, we inevitably touch on some of that anyway.

The most reliable sources – the Jewish historians Philo and Josephus – portray Pilate as a brutal, cruel governor with a lot of blood on his hands.

This is in contradiction with Christian traditions, which depict him as essentially either a good guy or as neutral. This obviously stems from the Gospels’ need to exonerate Pilate of blame for Jesus’s crucifixion – presumably for political reasons, since the Gospel authors (whoever they were) were putting out this material in a Roman world where it was dangerous to be seen to be demonising or vilifying the Romans. Hence, Pilate is depicted as not really wanting to crucify Jesus, but being forced into it by the Jewish authorities.

But then this got taken even further, with the tradition that Pilate was in fact a saint who ultimately converted to Christianity. There’s no evidence for this at all: but the Ethiopian Church, for example, upholds Pilate as a Christian martyr. Extraordinarily, in their tradition, Pilate – the man who supposedly ordered Jesus’s crucifixion – has been canonised and his saint’s day is June 25th.

The idea of Pilate’s martyrdom also lingered in Europe. There is in fact a site in Vienna (France) held to be the ‘martyr’ Pilate’s tomb.

It’s very odd for the man who supposedly ordered Jesus’s crucifixion to also be upheld as a saint or martyr.

You can see then that religious traditions are totally at odds with the contemporary Jewish/Roman sources: though the contemporary sources have to be regarded as more likely to be closer to the truth than all the fanciful ideas and reimaginings that were added on much later.

Again, most of the religious texts or traditions were probably not constructed as real history, but as folklore or a kind of poetry intended to strengthen faith or enhance spiritual convictions. This seems evident from even a plain reading of the Gospel texts, which frequently mention such and such happening ‘so that prophecy could be fulfilled‘ or such and such happening in order to evoke or reference a certain trope or archetype that was prevalent in the collective cultural consciousness of the day (riding into Jerusalem on a donkey, for example, or having the miraculous birth take place in the City of David).

Like many or most of the historic figures depicted in the gospels, such as Herod or even Simon the Magician, later writers, traditions and folklore felt free to imbue the historical Pilate with whatever actions, character, motivation or dialogue suited their purposes or the purposes of their message.

There certainly seems to have been a trend towards ‘redeeming’ Pilate in later Christian traditions and excusing him from culpability in the death of Jesus of Nazareth (an ongoing, expanded version of the very act of Pilate washing his hands of Jesus’s blood in the New Testament).

But was this whitewashing of Pilate purely based on political necessity: or was it motivated in part by knowledge or suspicion that the Roman governor may have actually played a role in aiding the historical Jesus or even in helping facillitate the spread of the Christian faith?

It’s interesting that Pilate has been ‘redeemed’ so much, while this is somewhat the opposite of how, say, Herod was treated: Herod was permanently demonised as the false king and the child slayer – in fact, there appears to have been no real evidence that Herod ever ordered the slaying of the firstborn children. As touched on in an older article about the Nativity narrative, it is very unlikely that something so horrific as the mass slaying of babies would fail to register in any of the contemporary writers’ accounts of the period or of Herod’s acts. Even writers who generally didn’t like Herod failed to mention any slaying of children – meaning almost certainly that this was a fiction.

In all likelihood, this story – like a lot of what was written into the New Testament – was both a case of political propaganda and also a narrative need to evoke the Pharoah’s child-killing spree in the Hebrew tradition: which again is referencing or echoing certain prevalent cultural archetypes in the way a storyteller might do while constructing an epic in any time-period or culture. Others elsewhere have made the case that some of the Gospel narrative – particularly the nativity story – were designed to evoke elements of the Moses mythology.

Certainly, the case has been made before that the entire Gospel narrative was depicting a kind of live acting out of a mystery play or passion play, but transposed onto real historical events or at least a real historical setting, for the sake of enhanced narrative power or spiritual potency.

This dynamic seems to be evident in the text of the Canonical Gospels at various points: for example, even the written Jesus at one point seems to imply that Judas is playing out a role so that the script can be fulfilled.

Under those circumstances, real historical figures are incorporated into the ‘play’, but the actions or words attributed to them can’t really be taken as what really happened. That doesn’t mean that the depiction of such a character isn’t broadly in keeping with the nature of the real historical figure: but there’s no way of knowing.

With all of that established, let’s come then to what is actually the main point of this article: an Easter Conspiracy Theory concerning the crucifixion/resurrection story – and in which the figure of Pontius Pilate may be seen as central.

My absolute favorite thing I’ve ever read about Pontius Pilate is the theory that Pilate facillitated a plot to spare Jesus from crucifixion.

Again, you could call it a 1st century conspiracy-theory masterclass, in which the Roman Governor conspired with other key figures to pull off a grand illusion.

I came across different versions of this idea in several books over a long period of time: The Passover Plot, The Jesus Papers, among others. My late grandfather had a lot of these types of books: so, when I was a teenager, I used to take books from his shelf and read them with keen interest.

The underlying point is that Pilate, who didn’t really have great cause to crucify Jesus, played out the crucifixion for the benefit of appeasing Jesus’s enemies: while in fact Jesus was never executed. Forgive me – I can’t remember which book forwarded which version of the theory. Some don’t focus on Pilate, while some have Pilate central to the whole thing.

But the idea that Jesus wasn’t crucified is a highly prevalent one, forming the basis of Jesus of the Apocalypse (Barbara Thierring), Bloodline of the Holy Grail (Laurence Gardner) and several other comprehensively researched and argued works that try essentially to piece together an alternate interpretation of the texts or an alternate history (claimed to be the true history that was covered up for centuries by the church).

The basic version of the Pilate conspiracy (which, I think, was forwarded first in The Passover Plot in the 1970s) is that Pilate conspired with Jesus’s chief followers and patrons (including the mysterious Joseph of Arimethea) to stage what would appear to be the crucifixion, while really allowing Jesus to escape and live on.

This is held to explain why Jesus was – according to the Gospel accounts – taken down so quickly from the cross when it was tradition to leave the dead bodies up on those crosses for a much longer period of time (often even days). It is thought to also explain a number of other Gospel details: chief of these being the mystery of the missing body in the tomb, but also details like Jesus being pierced in his side or fed vinegar on a sponge or the idea that the onlookers or witnesses to the crucifixion were made to watch from only from a distance.

There are more details than this – but I don’t want to reproduce all of it here, only touch on an overview.

Also, there are different versions of this: some where a substitute is placed on the cross in Jesus’s place (Simon of Cyrene, who is depicted in one of the Canonical Gospels intercepting Jesus while he is carrying his cross towards Golgotha) and others where Jesus himself in on the cross, but is fed a toxin by Simon the Magus (the vineger referenced in the tradition) to render him unconscious and thus simulate his ‘death’ for the crowd of onlookers, with the body being placed in the tomb by Joseph of Arimethea and later removed from the tomb in the dead of night.

He is then medically administered to by Simon the ‘Magus’ or ‘Magi’, who – it is argued – would’ve been an expert in such matters, due to his Magi background. It’s interesting to consider, if this was a grand illusion to stage Jesus’s death, that someone like Simon (the Magus, Magi or ‘Magician’) would be involved and might even have been its mastermind.

There’s also a version of this (I think in the Gospel of Barnabus) where Judas is the one crucified in Jesus’s place.

At any rate, the underlying theme is that Pilate allowed some of Jesus’s supporters to stage his death and secretly remove the living Jesus from his tomb. In some versions of this, all or most of the disciples and supporters are in on this: in other versions, only some people are in on this, meaning that others were genuinely baffled by the body going missing from the tomb (Mary Magdalene, for example, or the likes of Thomas and Peter – who are recorded in the Canonical Gospels as being dismayed, believing that the empty tomb meant Jesus had risen from death).

When I said at the beginning that it might’ve involved a conspiracy played out ‘to fool people’, the point is that it wouldn’t have been played out to fool entire generations of people or societies for hundreds of years (which would’ve been an unforeseen consequence of their conspiracy) – but merely to fool certain people there and then, in that moment and in that location (particularly those who wanted Jesus dead).

In terms of Romans intervening to protect problematic Jews in Judea from their own people, there is precedent elsewhere for this is in the plain texts of the New Testament: for example, Paul being apparently rescued from an angry mob by the Roman governor.

On the other hand, Paul had Roman citizenship and – according to some theories – might’ve even been a Roman agent who’s mission was to transform and reimagine early Christian thought into something entirely different, for the sake of helping Romanize what was initially a more Jewish tradition. I don’t know how valid that idea is or isn’t (or why the Romans later executed him).

There is also a popular argument these days that the Jesus character himself was an entirely Roman imperial invention of the Flavian dynasty: I haven’t been entirely convinced by that one myself, but it’s out there and a lot of people seem to believe that interpretation of events.

But bringing us back to the Staged Resurrection theory, this version of events also rewrites the entire ending of the Gospel narrative, removing the supernatural resurrection entirely and having it be that all subsequent references in Christian literature to post-crucifixion encounters with the ‘living Jesus’ were in fact non-supernatural encounters with the living Jesus, because he had never actually died.

Barbara Thierring’s books Jesus the Man and Jesus of the Apocalypse do a really fascinating job, for example, of going through the Book of Acts and tracking all the references to ‘appearances’ by Jesus long after the crucifixion – her argument being that these aren’t supernatural appearances, but coded references to flesh-and-blood encounters.

She argues that the Book of Acts itself is a coded narrative about the post-crucifixion Jesus’s real-world movements.

Michael Baigent, in The Jesus Letters, suggests that the reality of this alternate Pilate/Crucifixion story was one of the main things the Imperial Church was covering up for so long: terrified that it would undermine their grip on Europe’s populations if it spread.

If so, this would be no doubt only one among many things about the history of Jesus and Christianity that was being censored for centuries.

This reframes the New Testament books entirely, suggesting that the authors were actually knowingly writing of Jesus having survived the crucifixion and living on, essentially informing their contemporary readers that Jesus was alive: but that it was couched in terms of supernatural resurrection in order to preserve the living Jesus’s safety and protect him from his enemies.

In other words, the contemporary readers of those texts understood what it really meant – it was later generations and traditions that misunderstood the meaning, largely because the supposed writings of the outsider Paul of Tarsus confused things so much and even more so because, by the time the ‘canon’ was being consolidated, it was so far removed from the time, the people and the events they were talking about.

What one makes of this theory or interpretation of events depends entirely, of course, on how committed one is to the orthodox, canonical tradition: or how open one is to what you either see as ‘revisionist’ history or simply as long overdue critical thinking and reappraisal by objectively-inquiring minds in an era where the church no longer has the power to enforce its totalitarian control over discussion, literature and inquiry.

Obviously, these ideas probably don’t sit too well with some Christians, as it undermines the spiritual tradition that relies very heavily on the idea of physical death and resurrection. That is its biggest problem.

That doesn’t mean this version of the story isn’t closer to the truth, however.

There isn’t really a great deal to support the orthodox version of the crucifixion/resurrection story in terms of historicity: it’s something more based in faith and spirituality. Which is why, as I argued a couple of years ago, it is generally counter-productive to try to ‘validate’ the religious experience with historical ‘evidence’, because it’s probably both unnecessary and futile. A matter of ‘faith’ or spiritual conviction doesn’t really need to be defended or justified in those terms: and when people try to take in to that arena in order to validate it, they ultimately leave themselves open to plenty of counter-evidence or plausible counter-theories.

Some of those counter-theories, particularly the work of Barbara Thierring, make a very solid, convincing case. Thierring’s work in particular makes the case for the Gospels containing a coded, hidden narrative within the language of the plain, surface-level text (the ‘Pesher‘ code, as exposed by the Dead Sea Scrolls, which she lays out in Jesus of the Apocalypse): in her view, the Gospels were designed to be understood by one set of people (those initiated into the mysteries: or those ‘with ears to hear‘) in one way, while understood by everyone else (the common, non-initiated) in a different way (this different way essentially being what later became mainstream Christian belief as propagated in the New Testament and from Rome).

Her case is made so well that, once you’ve read her books, it is actually impossible to ever read the Gospels in the same way again.

Even various statements put into the mouth of Jesus himself by the Gospel authors seem to be suggesting this double-layer or dual-purpose nature of the texts – that they were designed to work on two different levels and to be understood by differently by different people. When read (or decoded) in this way, key events like the raising of Lazarus or the feeding of the five-thousand make much more sense than in the religious tradition (though, again, are probably a lot less dramatic or uplifting).

My own position has always been to hold two Jesus narratives in my mind: one being the very powerful, allegorical and mythological construct, and the other being the more likely ‘real’ history that has been largely covered up until the last century.

And it’s not simply a case of the last century seeing an opening up of free discussion or an emergence of researchers or academics wanting to challenge Christian orthodoxy: what really drove all of that was the emergence, after many hundreds of years, of things like the Nag Hammadi texts, the ‘lost’ gospels or the Dead Sea Scrolls, all of which restored a much broader context and a truer sense of the scope and variety of early Christian or Judaeo-Christian thoughts, interpretations and traditions.

All of which was lost or suppressed once Christianity became a controlled, dogmatic and imperial religion imposed by force: but which has only relatively recently been restored to public consciousness.

Again, we know that there were early Christian sects – as well as the pre-Christian sects of Jesus’s Jewish followers – that not only rejected the idea of Jesus as a God or as the Divine Son, but who also seemed to think Jesus survived the crucifixion.

It also features conspicuously in the apocryphal Gospel of Barnabus – in which it is suggested that someone was made to resemble Jesus and crucified in his place. Oddly, the Islamic version of Jesus’s story seems to be drawn more from the Gospel of Barnabus than from the Canonical Gospels of the New Testament, as the Muslim tradition also has it that God intervened to spare Jesus from death and that someone else was crucified in his place to fool his enemies.

In fairness, the Koran’s view on this matter has to be considered even less reliable than the New Testament, given that it emerged almost five-hundred years after the earliest gospels.

The Gospel of Barnabus is actually not a very good read, it has to be said; and its authenticity isn’t clear either in terms of its age or how it came to be discovered. In some ways, you kind of get why the four Canonical Gospels of the New Testament were chosen and so many others were rejected.

Arguably, a much bigger, more inclusive New Testament canon incorporating a wider range of gospels, texts and styles (The Gospel of Thomas, for example, which seems like it would slot into the canon very comfortably) would provide a much broader sense of the breadth and diversity of early Christian thought and the portrayal/perception of Jesus: however, it’s also arguable that limiting the canon to only four similar gospels provides more of a consistency and less confusion.

The Gospel of Barnabus, as I said, isn’t great reading: and it very much fails as any kind of inspiring religious message.

On the other hand, it has always seemed unlikely that the Islamic tradition concerning Jesus – however much merit it has or doesn’t have – would’ve been cooked up in a vaccuum or just to be contrarian: it’s more likely that the early Muslims were influenced by other Christian or Judeao-Christian traditions that were prevalent at the time in the Middle East, but by that point in time rejected by the Western/Roman tradition.

Logically, the early Muslim view of Jesus was more likely to have been informed by Middle-Eastern Christian sects and not by the version of the story being maintained in Europe: and it’s fairly well established by now that there were early Christian communities and traditions in the Middle East that followed a different version of the Jesus story to the one being propagated from Rome.

Whether the Gospel of Barnabus specifically was authentic or not (I tend to think it may have been a forgery), it wasn’t the only tradition that presented a different view of the crucifixion narrative.

It’s worth saying that, if the Staged Resurrection theory is true and the likes of Pilate, Simon Magus and Joseph of Arimethea did conspire to pull off an illusion, it doesn’t actually negate the spiritual idea or image of Jesus ‘suffering’ on the cross: he still would’ve been scourged, humiliated and crucified – and crucifixion was absolute agony.

It’s simply that, in this version of events, he didn’t die. But, depending on how one looks at it, it could even be maintained (from a certain point of view) that he was ‘resurrected’ – by the administrations of Simon Magus – from a type of ‘death’.

It’s not the Hollywood version. But it’s a fascinating alternate version of the story nonetheless.

And what about Pilate? What happened to him? Well, of course, we don’t know.

I have had a book for a long time called ‘Lost Books of the Bible‘: and the texts collected in this book are varied and often not very easy to read. Remarkably, the books of the Nag Hammadi Library don’t even feature in this collection – which just demonstrates how many Christian texts and traditions there were. And when you read a lot of these texts, you kind of sympathise with why so many of them were rejected for the New Testament: they’re just so diverse and so messy, while the Canonical Gospels at least have a degree of continuity and consistancy with each other that allows for the sustaining of a kind of overall consensus narrative.

But this volume includes several texts relating to Pilate: The Letters of Pilate, and finally the Death of Pilate.

Pretty much everything in these texts is probably unreliable and can’t be considered real history: that is to say not the true history of Pontius Pilate. However, they are ‘history’ in themselves, providing us with an insight into how early Christian communities or writers saw Pilate or what they said about him.

Which is, to be honest, ultimately how I view the books of the New Testament anyway: not a reliable source for real history, but essentially a rich and fascinating ‘history’ in and of themselves, regardless of how ‘true’ any of it is or of what type or definition of ‘true’ we’re even talking about.

The last of these texts details Pilate being brought to trial by Tiberius for the crime of crucifying the Jewish Messiah. Tiberius, according to this text, pronounced a death sentence on the former Governor of Judea. This presumably didn’t happen, as there’s no reason to think Tiberius would’ve even cared about this relatively minor incident in a far-flung corner of the empire, let alone put one of his own governors to death over it.

But it does give Pilate the epilogue that is missing in the New Testament. We’re told here that Pilate, seeking to spare himself execution, commits suicide instead: actually a rather common form of death for Romans suffering a perceived disgrace.

Whether it’s true or not is anyone’s guess – like all the rest of it.

But what’s always struck me about the Staged Crucifixion and Resurrection theory is that they transform the role of Pilate in the narrative – from a dithering and uncertain politician to something of a conspiracy mastermind (and on ‘the side of the angels’, so to speak: or at least on the side of what would become Western Christianity).

If this was what really happened, it also would mean that Pilate inadvertently and accidentally helped create what would become the largest religion in the world: that, by conspiring to spare Jesus from the cross, he paved the way for the spiritual belief in the death and resurrection to spread and flourish.

This would be an extraordinary accidental legacy for a man who presumably had no interest in Jewish religious thought or Messianic prophecies and who was, presumably, a normal adherent to Roman pagan religion who also held to the divinity of the living god that was his Emperor Tiberius.

I have no idea, of course, which version of this story is true – or whether none of them are true. But neither does anyone else and neither will anyone else ever. I present it here only because it’s so interesting.

It’s possible Jesus was crucified, died on the cross and rose from the dead: that’s certainly the more potent story and the one most people would prefer. If that’s what millions and millions of people have fervently and passionately believed for hundreds of years, down to the core of their spiritual beings, then that actually becomes a type of ‘reality’ in and of itself anyway – and it no longer matters what ‘really’ happened.

In that sense, the Gospels could be seen as the most astonishing and powerful work of spiritual alchemy ever conducted: not turning base metals into gold, or even water into wine, but turning allegory, symbolism and even sleight-of-hand, into what would become, for so many people over so many centuries, an intense and all-consuming spiritual reality.

Read more: ‘Pilate, Herod, Jesus & the Gospel Archaelogy‘, ‘Why Jerusalem is So Important to Apocalypse Fantasists‘, ‘The Life & Death of Augustus: 2,000 Years of Man, Myth & Reality‘, ‘History Struggling to Survive: The Palace of Nero & the Ben Hur Villa‘, ‘The Roman Ghost Legions – And a Meditation on the Nature of Time and Space‘…

Really interesting to read an alternate view on a story i’ve known for decades, but never really thought about critically untill now. Thanks!

B, I’m grateful you’ve posted such a thoughtful, serious, well-referenced response: this is precisely the kind of response/contribution to an argument or idea I’m usually hoping for. In all honesty, I thought I was being fair and balanced in the article: I tried to make it clear that I was just presenting some ideas because I find them interesting – and not that I’m trying to push them as The Truth or True Interpretation. Really, it’s just presenting an interesting alternate perspective or paradigm. You’ll note there were one or two other popular theories I mentioned too, but without giving them credence. But I find the Pilate theory genuinely interesting and so thought it was a worthwhile basis for an article. There’s nothing anti Christian about it: I don’t want you to have the impression that I’m trying to knock Christianity or debunk it, as that’s not where I’m coming from. I actually love the gospels as literature and as morality/spiritual ideas. But it’s my nature to be more drawn to historical inquiry, debate and a diversity of ideas, rather than any kind of Absolutism. I don’t like having Absolutes when it comes to religion. If it might’ve come across as being hostile to Christianity, then that actually highlights why I usually hesitate to write about religion at all – it’s very tricky to get the tone right or to be challenging without accidentally being either antagonistic or offensive at the same time. In my own opinion, I don’t think I’ve ever portrayed Christianity in a negative light – but I guess I’d have to read my articles through your own eyes, which obviously I can’t do. But doesn’t it also depend on what we mean by ‘Christianity’: do we mean just the Gospels themselves or do we mean ALL Christianity or anything that proclaims itself Christian? And do we mean modern Christianity or early Christianity? If we mean early Christianity, do we include the non-Canonical sources? Who decides? What about groups that wrote about Jesus and believed in him, but were later considered heretical by mainstream Biblical standards? What about Gnostics? It’s not so easy as to just say that only a specific set of books selected in Rome long after the fact should be considered the basis for ascertaining the true story. But to get to some of your very well selected points, I’m aware of the things you’re citing, such as Pliny, Claudius, etc, and they’re good points. I would also say there are details in the canonical gospels that suggest the story was based on things that really happened: for example, it would be odd for the authors to have Mary Magdalene as the first witness when they could’ve made it Peter instead, suggesting the fact of Mary being the one at the tomb was already so well known that they knew they couldn’t change it. I would say, however, that the age or dating of the gospels doesn’t actually say much about the underlying reality or nature of what they were writing about. In other words, very early dates for those manuscripts is fine – I wholly acknowledge that. But the Pilate-based argument is saying that there was a widespread misperception of what had transpired with the crucifixion and apparent resurrection – a misperception that ended up being a good thing, because the idea of Jesus conquering death and being unkillable actually gave the gospel so much more power. The message ended up being not that Jesus died a disgraceful death on the cross (and, as you say, why would they promote that?), but that he couldn’t be killed, he conquered death and rose from the grave – of course that’s a powerful message you would be happy to put out there. I’m not even necessarily saying I believe this version, just that it’s interesting: and that’s really the only point of it. I don’t have an absolute view on any of it at all: I’m just fascinated by all of it and always looking to expand, reconsider or replenish my perspective, without necessarily ever coming to any definite conclusion.

Thank you.

Rudolph Bultman writing in the second half of the 20th Century suggested faith did not depend on Historical evidence but on the witness of God’s spirit to a person through his word.

It is good to chat these things through. Thank again

My, my, my. I can only say that a person ought not base their faith, or lack thereof, on a speculative blog post.

My my my, I must have missed that reply? Basing their faith or lack, on a blog post. Historically BBB has often portrayed c in a negative light. Somewhere in the post it would oft comment on the lack of historical references from non biblical/religious sources. The reply was to add some references but also as its Easter, add some extra quotes/ref. I’ll go back into my cave now, wait to comment until Christmas, reply to a new Nativity conspiracy, where Mary and the Wise men dress up as angels and scare the shit out of the shepherds, who run to a stable, have a few shandy’s, see a donkey giving birth and start off a revolutionary cult that envelops the whole world (that being said BBB is still my go to Blog, and will be, Nativity conspiracy or none 🙂

Happy Easter

Has added fire in saying; ‘I have no idea, of course, which version of this story is true – or whether none of them are true’. These kinds of Jesus time, historical revisions, are usually ‘write-off’ alt. view attempts. Feel blasted by a zealot. Obviously not here. Last night did ‘debate of the century’ and Slavoj Zizek and Jordan Peterson. Amazing talking, while more an engaging dance than debate. Not only, got-going good on ‘the cross’, but Slavoj tells the ‘horseshoe story’ and why someone had one. Which then depends on which way/s to take the message? No matter what and find deceiving from said-presentation, when “does it matter… it works”, is the predominant question. Or, if some things found to be convincing would cause the cry the void and all forsaken. Jesus/God no more? Could it be? What might, or should, bring this about? The challenges are worth hearing but nothing conclusive. Not in my false-flag and hoax getting eyes. It does matter if there’s con thus contrary to the text. Well, the ultimate claim is God has somehow managed to ensure book/s got is, Book wants to communicate self-in. And so in this sense, until… and can’t imagine what could show the Gen. to Rev. are for sure full of historical porkies? — the Book and God are happening. A happening and with me. Will do a Plant a Seed on this terrific post but for now my Christian bro, Happy Bank Holiday Monday. One quick, can’t but knockback. On ‘became so warped and mangled in the three centuries or so or so after his lifetime’? As ‘B’ comments; hated, ‘ostracised, persecuted’. Had no ‘Bibles’ or buildings, illegal, difficult to join. Crazy love extended families. Convicting in so loving. Went from smashed about few thousands to 20 mill (third of known world) by the fourth century. Then came the state-run, or run-by, and the supermarkets are set up, aka denominations. The Gospel re-reshaping conspiracy in theology begins. In plain — re-read the text — sight. Unravelling. No horseshoe and ‘maybe bollocks but…” and me. God for getting and know the love and grace in action. ‘The account in the Acts …’ is ready for writing on. Grateful for the attention this piece brings. Thanks.

Yeah your point – and B’s point – about the persecution of early Christians is absolutely true and well attested. Which is why I dismiss the popular theory out there that the Flavians in Imperial Rome invented Jesus – it doesn’t make any sense. But one of the key things to get is that those early Christians and the post-Constantine Christianity are probably very different things. And when you try to get into pre-Imperial Christianity, you immediately have to face the fact it’s not so simple as saying there are only four gospels and a clear consensus. There were a lot of different communities, books and ideas. It can get confusing, but then I guess that’s how it was in those days. Lots of different people believed in Jesus in some form or another, but they had their own ideas and interpretations. Including someone like Paul. My understanding is that James and the Jerusalem Church weren’t happy about Paul’s ideas, for example.

Thanks for your response.

There were other ‘gospels if you like around, but if I may reference your Kurt Cobain Post, you suggest that the current authors, those that were not even alive at the time, are turning him into something he is not!

Proto Mark and Mark were attributed to Peter but written by Mark, an insiders account. Mark was around but only on the fringes.

Matthew and Luke used the early manuscripts and added to then depending on the audience. Matthew was around, Luke not so, however as a historian, he spend a long time in Jerusalem with Paul, I suspect obtaining original sources, eye witness accounts. Paul at this time was tested by James et al on his authenticity- he had been a violent persecuter.

John was hi top man. Didn’t use Mark – did his own.

Paul with his knowledge of the Old Testament, access to proto mark, Luke’s collection and the creeds that had been written down by this time started his missionary journey and planted small churches.

Timothy, Paul’s mate.

Jude Jesus brother. Same with James.

All knew him or had eye witness accounts. The others are not included as they don’t meet the strict criteria.

I agree that 1st 2nd century Christianity is nothing like today. It’s awful today and hope it goes to the margins sooner than later.

I accept all of that and have generally known it to be the case. I acknowledge too that most or even all of the apocryphal, gnostic or otherwise non-canonical texts generally have a later suspected date than the earliest known items of canonical gospels: though most of them are dated to within the first two centuries AD (and some to the 1st). The canonical gospels have a stronger claim to ‘authenticity’ at least in as much as they’re dated earlier. But I do stand by the point that any real exploration of 1st or 2nd century ‘Christianity’ has to, in all fairness, also take into account these other gospels and texts, even if one’s preference is to give priority to the New Testament canon. All of that being said, I enjoy discussing/debating these things: so thanks for making a conversation of it. I’ve always found all of this fascinating, which is why I occassionally try to delve into it.

An interesting side trip down my personal spiritual history, even if that history no longer holds any sway except in encounters with believing Christians – yes, I have known many non-believing, strictly traditional Christians so that’s not a contradiction. Do I care if Jesus ever was real or not? Only when considering the amount of damage powerful imperial institutions such as the Christian church have unleashed upon this world; damage and bloodshed the planet will never recover from for it has become a spreading poison, like radiation poisoning.

I appreciate that Sha’Tara, unimaginable cruelty. But I think you got it right when you say ‘imperial institutions. You wouldn’t be on this page, BBB, if you didn’t agree with him on Power, Money, Corruption and dare I say it evil. Pauls missionary journey are full of combat with those who want to control the growing church, over and over he challenges the church not to listen, don’t go back to bondage…you foolish Galatian’s who has bewitched you, is there another Gospel (besides freedom and grace)? Once pagan Rome adopted Christianity, the game was over! 300 or so years of persecution ended, the Pagan clergy jumped ship for honour and prestige took the pagan holy days put them on the Christian Holy days and Roman Catholicism was born, corrupted and was not challenged until 1517 by the Reformers. Another 500 years and we are back again to the same inept, corrupt, anti christianity, nothing remotely concerned with A Gospel of grace, a challenge to the Elite in its treatment of the poor. Nothing! Many church leaders are welcoming the move to the margins, none of us want the persecution of the 1st Century, but most believed thats where we’re heading. Look out for the uncompromising church then as opposed the the church that embraces the neo liberal version of Christianity. I hope you’ll find a home there.

Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) has — quite correctly — stated that “the most important theological issue today is ‘what is man,’ how do we understand the human person. That is particularly important both in our own Orthodox theology and in our discussions with other Christians.” I would add that the question of anthropology is also the fundamental lens through which modernity as a whole must be viewed and understood. Indeed, this question is at the very heart of nearly every challenge and difficulty faced by a Christian living in the present age.

I have written repeatedly that the modernity must be understood as a fundamentally religious phenomenon, and that secular humanism is in fact actually a forerunner of the religion of the Antichrist. This new religion is disguised from appearing as such, mainly because it professes not to worship any gods. But in reality, it is the worship of man. Its chief dogma was laid down by the Devil at the dawn of history: “ye shall be as gods.” And if modernity is the Religion of Man, then it is evident that its theology consists in nothing other than a new anthropology.

And although this new anthropology is profoundly hostile towards Christianity, it is nevertheless unavoidably derived from it as well. This is because, as Richard Pevear once wrote, “Demons are unoriginal. They cannot come up with anything new or real. Their lies are copied from sacred truths.” Indeed, it is precisely this core of sacred truth that gives Antichristianity all its seductive power and beauty. Antichristianity is not a lie, but a half-truth. Once again we see that Antichristianity means not merely “against Christianity,” but also “in place of Christianity.”

HIEROMONK GABRIEL

Difficult to give a brief reply to such a long comment. I’ll speak as a once committed disciple of Jesus Christ looking in vain for any remnant of any Christianity resembling and adhering to, the straight-forward teachings in the synoptic gospels. (I rejected the gospel of John and came to the conclusion that Paul of Tarsus was a false prophet installed and manipulated to create an anti-Jewish religion by stealing the Bible and appending his own writings to it. Paul was an anti-semite therefore likely not a real Jew.)

In any case and jumping to today, what I see is Christianity as an utterly corrupt form of worship that focuses on the hubris of salvation, exclusivity and monopolistic exceptionalism. The real god of Christians is Mammon, the head of current predatory capitalism. As for the god of the Hebrews/Israelites/Jews, that has morphed onto a combination of many ancient gods, essentially a meaningless imaginary entity surviving in the minds of those who still call themselves ‘Christians’ while having no clue as to the many ways they condemn themselves in the eyes of the world by using that label. A Christian today is a racist, homophobic, war-mongering, money worshiping fear and hate-filled person. The modern Christian gospel is summed up in three words: health, wealth and happiness.

I was baptized and raised a Catholic, and also attended Christian vacation bible school as a child, but started actively questioning religion in my late teens. By the age of 20 I was an Atheist, and have been so ever since. I don’t believe any of this stuff.

You have to be, 100%, my favourite, go to, blogger, but I don’t know what happens to your thoughtful, intelligent, critical analysis when you write about Christianity. Maybe you were an alter boy or something, went to a catholic school, a fog (incense) comes over you as your pen away.

Cui Bono? From this CC you imagine. The 12 disciples? They were hated, ostracised, persecuted, not only by the Jewish elite but Rome. Why carry on the farce? It’s like all the collaborators of 9/11 are being killed off, so they admit the conspiracy…it was us, no planes and no jet fuel! Stop killing us! We give up! They kill people to keep the lie going. Those guys established a self sacrificial, loving community serving and caring for the poor and lame. Why bang on about a bloke, God, who had the most horrific death known in the ancient world. Romans couldn’t even say the word.

“We preach Christ crucified,” St Paul declared, “unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness.” He was right. Nothing could have run more counter to the most profoundly held assumptions of Paul’s contemporaries – Jews, or Greeks, or Romans. The notion that a god might have suffered torture and death on a cross was so shocking as to appear repulsive. Familiarity with the biblical narrative of the Crucifixion has dulled our sense of just how completely novel a deity Christ was. In the ancient world, it was the role of gods who laid claim to ruling the universe to uphold its order by inflicting punishment – not to suffer it themselves.

Unless there was something so earth shattering that they witnessed, that all they could do was tell others that Christ had indeed risen, and the curtain had been torn in 2…a new covenant with the creator of the Universe. Good had defeated evil, death was conquered.

James, the brother of Jesus, surely he would have gone, enough mate, this is getting too risky! We know he lived at least five years after the death of Christ because of mentions in the Bible. According to tradition, James was thrown down from the temple by the scribes and Pharisees; he was then stoned, and his brains dashed out with a fuller’s club.

Paul and Peter killed in Rome, The others killed while too while preaching.

Reporting on Emperor Nero’s decision to blame the Christians for the fire that had destroyed Rome in A.D. 64, the Roman historian Tacitus wrote: (A Real Conspiracy)

Nero fastened the guilt . . . on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of . . . Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome. . . .{5}

Pliny the Younger to Emperor Trajan. Pliny was the Roman governor of Bithynia, inA.D. 112, he asks Trajan’s advice about the appropriate way to conduct legal proceedings against those accused of being Christians.{8} Pliny says that he needed to consult the emperor about this issue because a great multitude of every age, class, and sex stood accused of Christianity.{9}

At one point in his letter, Pliny relates some of the information he has learned about these Christians:

They were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ, as to a god, and bound themselves by a solemn oath, not to any wicked deeds, but never to commit any fraud, theft or adultery, never to falsify their word, nor deny a trust when they should be called upon to deliver it up; after which it was their custom to separate, and then reassemble to partake of food–but food of an ordinary and innocent kind.{10}

“The Christians, you know, worship a man to this day – the distinguished personage who introduced their novel rites, and was crucified on that account . . . You see, these misguided creatures start with the general conviction that they are immortal for all time, which explains the contempt of death and voluntary self-devotion which are so common among them; and then it was impressed on them by their original lawgiver that they are all brothers, from the moment that they are converted, and deny the gods of Greece, and worship the crucified sage, and live after his laws. All this they take quite on faith, with the result that they despise all worldly goods alike, regarding them merely as common property.” [4. Lucian of Samosata, The Death of Peregrine, 11-13]

They are not going around killing people to become Christian. Yes, the crusades, inquisition etc were evil, no denying, but by that time Christianity was lost to power and prestige, like today. They however preached a Gospel of Grace and gave up materialism, even when they were bing kicked out of various Cities.

“As the Jews were making constant disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus [variation of Christus, Christ], he [Claudius] expelled them from Rome.” [2. Suetonius, Life of Claudius, 25.4] (In the biblical narrative, Luke refers to this event, which took place in AD 49, “There he met a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus, who had recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla, because Claudius had ordered all the Jews to leave Rome. Paul went to see them . . .” (Acts 18:2)

Luke was classed as a first rate Historian -a veritable Carol Quigley!

As a final example, Saint Luke calls Iconium a city in Phyrigia. Who cares? Well, this was also a major rub against the credibility of Luke for centuries. Scholars, going all the way back to writings from historians like Cicero, maintained that Iconium was in Lycaonia, not Phyrigia. Therefore, scholars declared that the entire Book of Acts was unreliable. However, In 1910, Ramsay was looking for the evidence to support this long-held claim against Luke and he uncovered a stone monument declaring that Iconium was indeed a city in Phyrigia. 7 Many archaeological discoveries since 1910 have confirmed this.

When reviewing the research and writings of Saint Luke, Famous historian A.N. Sherwin-White declares: In all, Luke names thirty-two countries, fifty-four cities, and nine islands without error.

For Acts the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming. . . . Any attempt to reject its basic historicity must now appear absurd.

Following his last great missionary journey, the Apostle Paul returns to Jerusalem. There he is arrested and sent to the Roman provincial capital of Caesarea, where he is tried and eventually transported as a prisoner to Rome, to appear before the emperor’s court.

The account in the Acts of the Apostles of Paul’s voyage to Rome, and his shipwreck en route, is supported by a wealth of historical detail. No other passage in the New Testament has such a striking evidential confirmation of its historical accuracy. Not only are the political, social, and legal details of the voyage and shipwreck striking in their accuracy, but also the meteorological and nautical details

https://carm.org/manuscript-evidence

As you can see, there are thousands more New Testament Greek manuscripts than any other ancient writing. The internal consistency of the New Testament documents is about 99.5% textually pure. That is an amazing accuracy. In addition, there are over 19,000 copies in the Syriac, Latin, Coptic, and Aramaic languages. The total supporting New Testament manuscript base is over 24,000.

Almost all biblical scholars agree that the New Testament documents were all written before the close of the First Century. If Jesus was crucified in A.D. 30., then that means the entire New Testament was completed within 70 years. This is important because it means there were plenty of people around when the New Testament documents were penned–people who could have contested the writings. In other words, those who wrote the documents knew that if they were inaccurate, plenty of people would have pointed it out. But, we have absolutely no ancient documents contemporary with the First Century that contest the New Testament texts.

Furthermore, another important aspect of this discussion is the fact that we have a fragment of the gospel of John that dates back to around 29 years from the original writing (John Rylands Papyri A.D. 125). This is extremely close to the original writing date. This is simply unheard of in any other ancient writing, and it demonstrates that the Gospel of John is a First Century document.

Happy Easter:-)