The Nobel Committee’s considered decision to try to focus attention on the subject of child suffering comes amid a resurgence in forced child labour and child trafficking for both labour and sexual abuses in various parts of the world.

Child hunger and homelessness have also become a massive problem of the 21st century, particularly as a result of the three-year Syrian Civil War, though the phenomenon isn’t limited to Syria by any means.

It is extraordinary that these horrors are transpiring on so vast a scale in the year 2014, representing a failure of global civilization and human society.

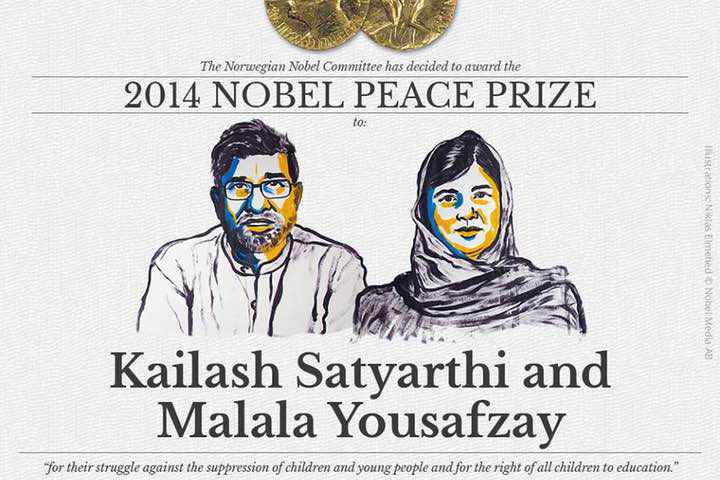

Yesterday the now world famous Pakistani teenager Malala Yousafzai and tireless Indian campaigner Kailash Satyarthi received their shared Nobel Peace Prize. Celebrated as “champions of peace”, one Nobel official said he hoped the award would encourage others around the world to fight for the rights of the young.

The Nobel Committee this year had focused the peace prize on the pressing theme of child suffering throughout the world; as such, both Malala Yousafsai and Kailash Satyarthi emerged as prime candidates for their respective work in the field of children’s issues in the world.

The 17 year-old Malala, shot in the head two years ago by the Taliban in Pakistan, has been a tireless advocate for the rights of girls to education, while Mr Satyarthi has been acting to directly intervene in the lives of maltreated children for over three decades in a manner that without question qualifies him as a social ‘hero’ in the truest possible sense.

The now Birmingham-based Malala has become a cultural icon and high-profile voice in the two short years since the near-fatal shooting that brought the one-time blogger to international notice. Guided in part by her father, she has used this growing profile to speak out wherever possible on the issues of girls’ rights in particular and children’s plights in general, including the ongoing plight of Syria’s children. This has included speaking directly to the UN and meeting with Barak Obama in the White House.

Given her remarkably young age, her level of influence and stature is already extraordinary; but it may grow greater yet in coming years.

She has already spoken of her desire to enter into politics and possibly become Prime Minister of Pakistan some day, which would be an extraordinary path and one fraught with very real dangers (witness the assassination of Benazir Bhutto); but as she has already demonstrated, a brutal assassination attempt has not discouraged her from her campaigning.

“The so-called world of adults may understand it, but we children don’t,” Ms Yousafsai said in acceptance of her award. “Why is it that countries which we call ‘strong’ are so powerful in creating wars but so weak in bringing peace?”

She brought with her to the Oslo ceremony other young girls who have endured similar ordeals as her, including two classmates shot alongside her by the Taliban. Many in Pakistan may be less than unanimous in their approval of Malala’s activities and profile (and many more in Western-based social media platforms and comments sections have also been disparaging lately), but her speech in Oslo yesterday (and Mr Satyarthi’s even more so) was met with enormous applause, cited by some present as the most moving in recent memory.

Her co-laureate Kailash Satyarthi in some ways is someone who should have an even higher profile than Ms Yousafsai; Satyarthi founded the organisation Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save the Childhood Movement) in 1980 and has successfully worked to protect the rights of an estimated 80,000 children. Through the work of the 60 year-old Mr Satyarthi (dubbed by some in India as ‘the new Gandhi’) an enormous number of children have been rescued from forced labour and hazardous industries. His organisation carries out dangerous rescues of child labourers, many of them having been sold into this virtual slavery by their incredibly poor families.

Mr Satyarthi has encountered continuous death threats for his endeavours and members of his movement have been killed. Remarkably, though Kailash Satyarthi’s work has impacted the lives of hundreds of thousands of children, until he was announced as a Nobel Peace Prize recipient, he was generally not a very well-known figure outside of India (although his work has previously been celebrated by Gordon Brown).

Due to the rise in his profile following the Nobel announcement, his Twitter account shot up from a mere 100 followers to over 5,000 in just a few hours. It highlights the fact that some of the most important people in our societies, some of those most worthy of the most coverage and support, are some of the least known; numerous commentators in India have admitted they’d never heard of Mr Satyarthi or his work until now, yet he is now being written about as a national hero.

The perverse reality, however, is that so many of these vast crises in the world could be solved if the funding and focus was put towards them by the forces and institutions in control of the lion’s share of the world’s wealth.

The plight of the Syrian children, starvation, malnutrition and famines in Africa, child trafficking in various countries; all of these sicknesses of our age could conceivably be fixed with a sustained, concerted effort by the world’s most powerful, wealthy entities and institutions; and by concerted and genuine criminal investigations.

Mr Satyarthi in his Oslo speech makes this point by pointing out that “just one week of military expenditures can bring all children to classrooms.” The Nobel laureate goes on to say, “I refuse to accept that all the laws and constitutions and police and judges are unable to protect our children,” he says in his speech.

Last October the International Labour Organisation estimated that although the figures for forced child labour had dropped by a third since the turn of the century, the estimate still stood at 168 million children. While some mistakenly perceive slavery to be a thing of the past, it is important to remember that child slavery, child trafficking and forced labour are major global issues of the 21st century. It is certainly a contemporary problem in Mr Satyarthi’s Indian homeland (where the archaic caste system is still upheld as inviolable by vast amounts of the population), but is also a major problem in Africa and other parts of the world.

Further, according to Unicef, 22,000 children worldwide die each day due to poverty. Around 15 million girls are reported to be forced into child marriages around the world every year. One in three girls in the developing world are married by their the age of 18, curtailing their chance to have an education.

But the Nobel Committee has brought wholly warranted recognition to two extraordinary individuals whose work deserves all the coverage and support it can be given.

And in so doing, it has brought fresh attention onto major society-spanning problems of our time and a continuing stain on the collective conscience.