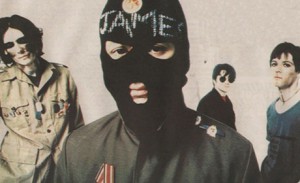

February 1st 2015 marks twenty years to the day since Richey Edwards went missing; twenty years since his car was found abandoned near the old Severn Bridge, leaving no traces as to his whereabouts.

Wherever he went, whatever the ultimate truth about his disappearance, the lyrical genius behind one of the greatest albums in the history of modern music is still being celebrated and talked about two decades later, the subject of unending adoration from his fans who’ve never stopped thinking about him in all of that time.

Kate, a Manics fan in London, was sixteen when Richey went missing and she still remembers it. “It was like I kept imagining there would be an announcement, a news story, that he’d been discovered alive and well somewhere; that the whole thing had been an accident, like he’d lost his memory or something and had gotten lost. And then as more time passed, I realised that wasn’t going to happen and began to accept there would never be a definitive answer to what happened. But I think about him all the time; and there’s not a week that goes by that I don’t listen to The Holy Bible.”

That probably sums up the attitude of many Manics’ fans; certainly of Richey’s fans in particular.

Richey’s sister, Rachel Elias, recently gave moving interviews to ITV News and various other outlets in commemoration of the anniversary of her brother’s disappearance. “Even though we had Richard declared legally dead (in 2008) that hasn’t assisted us in anyway dealing with the loss of him. That process was just a financial matter,” she said. “I think unless somebody returned or you recover their body or you at least know where they are – even if they don’t want to return – that would resolve the matter.”

In the meantime Rachel wants people to remember her brother as a gifted writer rather than merely a tragic figure or the “cult of Richey” caricature that he has unfortunately become to many, the same way Kurt Cobain has to a lot of people.

I recently came upon the extracts from reportedly the very last interview Richey ever gave, conducted by Japanese music journalist Midori Tsukagoshi at the guitarist and poet’s Cardiff flat in 1995. While not hugely revelatory in any way, the quotes from Richey offer a timely insight into his nature and some of his preoccupations, perhaps reminding some of us of why he was not only an extraordinarily special lyricist, wordsmith and artistic force, but also a highly endearing personality in the basic sense. “It’s very important for me to understand things,” Richey says in the interview. “Like, last summer I’d sit thinking about the smallest things over and over. But it’s difficult to live in that frame of mind. It means you can’t move. Back then I was living on my own, without anyone to speak to. I didn’t even have a telephone.”

“I have no regrets,” Richey said. “Regrets are meaningless. You can’t change yesterday or tomorrow. You can change only this present moment.”

Personally, I remember being somewhat numb about Richey’s disappearance in 1995, not knowing how to feel about it and therefore generally avoiding thinking about it or paying attention to stories. I had been obsessed with The Holy Bible at the time (as a 14-year old), which is widely regarded as Richey’s defining statement and an overall masterwork, and then found myself unable to listen to the album at all from February 1995 until at least couple of years later.

It was only some time after the band continued on and made the extraordinarily life-affirming Everything Must Go album as a three-piece that I was able to listen to the older stuff again.

I discovered Joy Division only some years after I’d already been a Manics fan, but I’ve often thought there was a lot in common between Richey and Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis, who also suffered severe depression and was an intense, though highly intellectual individual who wrote dark, evocative lyrics. Curtis committed suicide on the eve of what would’ve been a breakthrough US tour for Joy Division, while Richey went missing the day he was supposed to be flying to the US for a major promotional tour. The more time has passed, the more I’ve come to the view that Richey was his generation’s Ian Curtis.

I’ve often wondered what Richey would’ve been like as a frontman in his own right; not in place of James Bradfield, of course (you can’t replace James in a million years), but I mean just in some side project or solo effort. It would’ve been interesting to see him sing his own lyrics, were he a singer.

I’ve also wondered if the fact that he wasn’t a singer somehow enabled him to write lyrics in a much freer way, knowing that it was James who would have to interpret the words phonetically; something that James has openly said he found difficult sometimes. Yet James without exception channeled and interpreted those lyrics powerfully and beautifully, somehow always coming across as though he fully felt and embodied those lyrics, even though in some cases he might not have entirely understood where Richey was coming from. If someone with no knowledge of the Manics was hearing, say, ‘Faster’ for the first time, I’m sure they wouldn’t suspect James hadn’t written the lyrics; they’d think James was passionately belting out his own poetry.

In essence, that’s the power of the Manics’ dynamic on those early albums; Richey and Nicky (Wire) were extraordinary lyricists, but James was exactly the dynamic and powerful frontman who could give those lyrics sonic and visceral power.

I hadn’t expected the Manics’ to continue after Richey’s disappearance 1995, but have always been so glad that they did, because the Manic Street Preachers, in all honesty, are probably the greatest British band of the last thirty years. They’ve done some tremendous things since and their fan-base – quite possibly the most dedicated fan-base in all of rock – has been with them at every step.

Richey’s spirit continued to be present with the band’s music long beyond The Holy Bible, most directly of all of course on 2008’s Journal For Plague Lovers, which in essence could be regarded as a posthumous Richey-written album being made more than a decade after he went missing. That’s a pretty extraordinary thing and it was testament to how prolific and creative Richey was. And that’s not even accounting for the fact that he may have thrown away a whole lot of his notebooks of lyrics and ideas too; a fact he alluded to himself in that final interview.

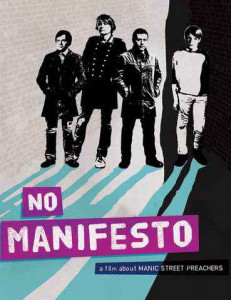

Meanwhile with their latest album Futurology released last year, The Holy Bible anniversary release, the earth-shattering Holy Bible gigs last month, and now the release of the exciting Elizabeth Marcus Manics’ film No Manifesto, it has been a highly exciting and active time for the band and for their multitudes of fans.

In all of this, however, Richey Edwards is never far from people’s minds, his spirit abiding with both the band and the band’s audience.

Meanwhile alleged sightings of Richey in various faraway locations, most notably in Goa, India, have continued sporadically. This mythology of Richey having fled to Goa was something that developed quite early and wasn’t as outlandish or overly optimistic as it might’ve appeared to some, as this piece from The Independent in 1997 illustrated.

But talk of ‘Richey sightings’ even twenty years after his disappearance are probably not all that helpful to his family or friends in their longstanding need for closure.

This is an example of an alleged ‘Richey sighting’ (probably fake), the kind of which most Manics fans are probably fed up of by now, but which some (perhaps understandably) tend to obsess over. The nature of Richey’s disappearance made this kind of cult of mythology pretty much inevitable. Such stories might still be being reported for years and years to come, forming a part of modern folklore and mystery.

I personally chose to believe, even in 1995, that Richey wasn’t still alive, simply for this reason; that he’d never seemed like someone who would deliberately subject his family or friends to the uncertainty and lack of closure. Unfortunately people in a depressed or uneven state of mind don’t always behave logically or in a tidy manner; I always assumed that he assumed everybody would understand that he was gone.

That was just my view of it, however; everyone is entitled to have their own view of it and their own feelings about it.

And people certainly do have their own views and their own feelings about the disappearance of Richey Edwards, even two decades later.