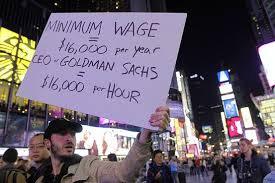

On 17th September 2011, Occupy Wall Street gained enormous worldwide media coverage. The people were revolting against the corporate control over society, against the criminal bankers and their vassal government officials, against injustice and inequality.

It felt like, and could’ve been, a defining moment of a generation; it could’ve been world-changing.

In the same year as the Arab Spring and the ousting of the Egyptian and Tunisian governments by apparently popular people’s movements, the West, beginning with America, now appeared to be following suit.

By 9th October, Occupy protests had taken place or were ongoing in over 951 cities across 82 countries, and with over 600 communities in just the United States. Regardless of however unflatteringly the corporate media chose to portray it, there was a palpable excitement and sense of momentum in the air. But, as Micah White says, “it failed”.

“And when you reach that point, instead of repeating the traditional protest behaviors, screaming and holding posters, you have to innovate,” says the former Adbusters editor in a recent interview with Brazil’s CartaCapital about his book, The End of Protest. Micah, a driving force behind the Occupy movement, was speaking with CartaCapital during his recent visit to São Paulo. It is difficult to argue with his observation. That we are inhabiting the period of the ‘largest protests in human history’ must be true. I’m not aware of any period in recorded history where so much protest and activism was going on so regularly (other than the Civil Rights movement; though that was an American issue and not a time of global protest).

There is in fact so much protest going on that it becomes commonplace, loses its edge and becomes easy to ignore. Once a model of protest has consistently failed to accomplish its objectives, it loses its momentum and is no longer seen as a ‘threat’ by the Establishment, but merely as a nuisance to be monitored and contained.

There is surely a difference between potent protest that might accomplish something and what we are now observing so much of the time, which is simply mass venting of frustration and almost ritualistic expressions of collective anger by enormous numbers of people who want their voice heard but realise they are essentially being rendered impotent.

Two months ago, the day after the Conservative government in the UK won the General Election, there were protests and marches in London: it changed nothing – and it couldn’t really have changed anything anyway, as it had no specific or feasible objective. Recently there were large protests against the government’s welfare cuts and social cleansing programme – and on the *same day* the government announced more, bigger cuts: that’s how little the current model of protest is working.

Not only is it not working, but it is regarded with derision by the people and institutions who are *supposed to be* threatened by it (or at least worried by it – which they are clearly not).

In part, this may be because Occupy and protest in general eventually just becomes a sort of institution itself; an established and expected part of the culture. Everyone becomes familiar with it, and with the existence of the widespread disaffection and dissatisfaction, but it ceases to be a ‘problem’ and is instead simply incorporated into the status quo. The corporations, the corporate-controlled governments and the corporate media simply frame the protest movement however they wish to in their limited coverage and everything rolls on, unchanged.

The model of protest itself becomes redundant and easy to ineffectualise, and in fact the more ineffectual it all appears to be, the more the likelihood that many of those doing the protesting lose their enthusiasm for it.

According to Micah, speaking to CartaCapital in Sao Paulo, “In addition to a crisis in representative democracy, there is a crisis in the model of activism, how people protest. There is a crisis in the power of people to force governments to do what they want. We live in a time when there appears to be no way for ordinary people to influence their governments through protest… This means there is no democracy.”

In another recent talk, he offers his advice for the next generation of social movements: “Never protest the same way twice.” In a talk with Brazil’s biggest daily newspaper, Folha de Sao Paulo, the 33-year-old activist and consultant says, “Attracting millions of people to the streets no longer guarantees the success of a protest.” The Occupy Wall Street co-founder is talking about the need to move beyond the stale model of ineffectual mass demonstration. “The only way to remove the power of corporations in our society would be to create a social movement capable of winning elections. Now it is clear that the only way to win power is to create a hybrid between a social movement and a political party. Something that does not have leaders, but has spokespeople and an organizational structure that lasts more than six months,” he argues.

My own attitude towards the Occupy movement has always been mixed.

Of course at the basic, fundamental and moral level, I could never be anything other than a supporter. The problem with being ‘part of it’, however, is that you very quickly end up asking “part of what?” Other than a general feeling of malaise and disenfranchisement with the prevailing Establishment, System and Corporataucracy, the question could be asked (and frequently is): what was being accomplished? The financial establishment simply weathered the storm, waited for it to lose momentum, and then carried on with business as usual. And not merely business as usual, but an escalation of the most ruthless propagation of corporate government, inequality and financial criminality; to the extent that, now in 2015, we are actually in a worse situation than we appeared to have been in 2011.

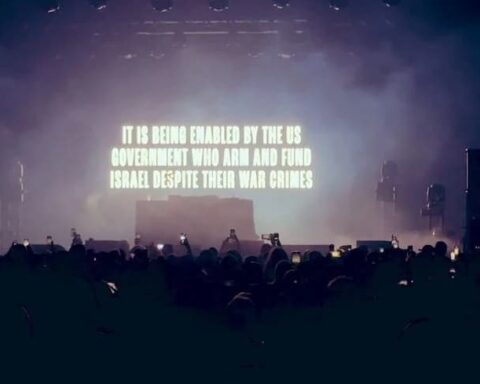

It was the height of irony that in the same year, in the same months, that Western Capitalist governments – led by America, Britain and France – were bombing Libya back into the stone age and providing arms, funding and air-support to a so-called ‘pro-democracy protest movement’ in Libya as part of the ‘Arab Spring’, the same corporate-run governments were utterly ignoring millions of its own protesters and in some cases even sending in armed police to control them. We had a globe-spanning, multi-national movement of peaceful, non-violent protest against our own corporatist governments and it accomplished very little, and moreover was ridiculed by much of the mainstream media establishment; and yet in Libya our governments were directly championing and supporting ‘protest movements’ (which were in reality more armed uprisings than protests) and making long speeches about ‘the voice of the people’ and the ‘legitimate protests’ in those countries.

This is particularly galling in the case of Libya, because in essence, in 2011, while the vast Occupy protests were going on all over the Western world and complaining about the injustice of the corporate-controlled government and the disillusion of the 99%, those same Capitalist governments were utterly laying waste to Socialist Libya – a society in which fair distribution of wealth was a major, central principle.

The Gaddafi allusion is also relevant on another level. The mass protests of the ‘Arab Spring’ were constantly cited as an inspiration for the Occupy movement. The movement’s leaders and instigators frequently said that the nature and success of the protests in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Syria, etc, were an encouragement that the same sweeping change could be brought about in Western societies too. The problem with this view is that it is based on only a surface understanding of the nature of the ‘Arab Spring’ and what was going on in 2011. While the extraordinary events in Tunisia and Egypt can genuinely be regarded as a triumph of grass-roots political protest/activism to bring about enormous change, there was a more sinister reality to the so-called ‘protest movements’ in Libya and Syria: which is that, assuming there *were* any genuine protests in Libya or Syria at all, they were in reality very small protests that were subsequently hijacked and taken over by armed groups, terrorists, extremists, and most importantly of all by foreign military/intelligence agents.

More than that, there is very strong evidence to suggest that the ‘widespread protest movements’ in Libya and Syria were largely illusions concocted and maintained by Western governments and corporate media.

The reason I bring this up is because it hints at a potential danger to Western activist movements such as Occupy: specifically the danger of such movements and protests being infiltrated, hijacked and utilised by intelligence agencies or by operatives of the very Establishment that the activism is trying to change. There was in fact plenty of testimony fairly early in the Occupy movement suggesting that the movement and the protests were already being infiltrated and undermined. Patrick Howley, an assistant editor for the American Spectator, for example wrote a column bragging about his role as an agent provocateur.

Kevin Zeese and Margaret Flowers (Occupy Washington DC) touched on this problem not long after the initial outbreak of protests, highlighting the problem of Occupy opponents embedding themselves into the peaceful protests and trying to incite trouble.

For example; ‘we uncovered the second infiltrator when he was urging people on Freedom Plaza to resist police with force.’ This well-known, tried-and-tested infiltrate-and-undermine technique, which traditionally involves intelligence agencies, is of course thoroughly to be expected. There were frequent claims that police and intelligence undercover personnel were infiltrating Occupy protests to cause trouble, spark ‘incidents’ and alter the tone of the protests.

In his talk with Folha de São Paulo, Micah White also touches upon the role of Social Media and how, contrary to the widespread view that it mobilises and empowers activism and revolution, actually undermines the potency of protest and makes people complacent. “Social Media has a negative side, which goes beyond police monitoring. During Occupy, we experienced it: things started to look better on social networks than in real life. Then people started to focus on social media and to feel more comfortable posting on Twitter and Facebook than going to an Occupy event. This to me is the biggest risk: to become spectators of our own protests.” And that is certainly what appears to be happening now; that those who go out en-masse into the streets are basically ‘spectators of their own protests’.

His mention of Social Media is also particularly relevant in my opinion, albeit in a way that the Occupy co-founder might not himself realise. Because those of us who’ve studied the Arab Spring, particularly in the case of Libya and Syria in 2011, know that social media (Twitter, Facebook, even You Tube) is often hijacked by intelligence/military agencies. For example, the US military secretly contracted HBGary Federal to develop the software that would allow for ‘the creation and use of multiple fake social media accounts’ for the purposes of ‘swaying public opinion’ and ‘promoting propaganda’; this was in February 2011 and was for the immediate purposes of faking the Libyan and Syrian ‘pro democracy’ movements on social media – managing multiple social-media accounts passed off as being the real accounts of Libyan and Syrian civilians (for more on that, see my book ‘The Libya Conspiracy‘).

This fake social media pantomime being played out enabled an orchestrated collapse of Syrian society and the collapse of the Libyan state itself. The point here being that – at any point in time – the same techniques could be used via social-media to entirely hijack online activity in regard to movements like Occupy, the Black Lives Matter campaign, and other such protest/activist groups.

The ‘Social Media Revolution’ can be seen therefore to be highly vulnerable. Aside from that, it does also, as Micah says, simply risk making people lazy.

So is protest dead? Is it impotent and does it accomplish anything? Well, the Establishment forces would certainly like people to feel impotent and to feel that protest is pointless. History of course indicates that protest isn’t impotent and can accomplish a great deal. Just think back to Gandhi, the Suffragettes, Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights movement, for example.

For that matter, we can also look to Tunisia in 2011 – the sole success story of the ‘Arab Spring’.

Naomi Wolf makes some very interesting points based on her study of protests and has clear view on when they are effective and when they are not. She describes how the only effective protest is one that interferes with the normal course of business (or, as she says, “stop traffic”).

In her view, protest is being regulated to the point of ineffectiveness; for example, in the ‘permit process’ and the police regulating where protest is allowed. The key to potent protest, Wolf points out, is to violate those rules, break the law and expand our rights to Freedom of Speech, Right to Association and right to petition the government for grievances.

A study of the history of effective protest, in her view, suggests that for protest to work it should not obey the limits of the law or allow police to regulate them.

Micah White, meanwhile, refutes the notion that Occupy has been a complete ‘failure’ or that it hasn’t made any difference. “The real benefit of Occupy Wall Street is that it taught us the contemporary ideas and assumptions we have about protests are false. My main conclusion is that activism has been based on a series of false assumptions about what kind of collective behavior creates social change. I think the standard forms of protest have become part of the typical pattern. It’s like our protests are expected. And the key is to constantly innovate the way we protest because otherwise it is as if protest is part of the script. It is now expected to have people in the streets, and these crowds will behave in a certain way, and then the police will come and some of the people will be beaten up and arrested. Then the rest will go home.”

Effective activism, he argues, is to be accomplished by a much simpler process of awakening; via the spread of ideas and information. “What I am proposing is a type of activism that focuses on creating a mental shift in people,” he says. “Basically an epiphany.”

In essence, however, what he is describing sounds more like simple journalism and information exchange/dissemination on a mass scale.

And he is probably right.

Knowledge is power, as they say; and information and ideas are probably far more effective than placards and V For Vendetta masks. The placards and masks have their own sort of power, however; and those, particularly in the mainstream media, who like to portray Occupy as having ‘failed’ or having been misguided, are wrong. Because even if such protests have failed to change systems or behaviour at the governmental or corporate level, they have certainly succeeded in radically altering the popular consciousness, changing the dynamics of the social and political landscape and made mass protest the norm.

That degree and frequency of mass protest – as well as, more importantly, the things that are being protested against – could impact things not just for this generation, but generations to come.

A generation or more of mass protest to come – and the vast mobilisation of the ‘99%’ – is a victory in itself; it might not be the ultimate victory, but it’s still a victory and it still sends a very strong message to the powers and institutions controlling our societies.

They may be intent on maintaining corrupt and eroding systems of injustice and imbalance, but they do not do so with our consent – and every time masses of protesters go out and make their voices heard, they are reminded of that fact.

So, how’s that whole “changing the world” thing going for you guys? Did you ever even manage to come up with a unified message?

Interesting stuff … I should probably write a post on this but I’ll try a comment first. Having been very excited when Occupy Wall Street emerged I felt obliged to go to my own city’s Occupy site and actually do something instead of just watching on the social media. I am quite old and it was like revisiting my youthful activism which didn’t last long for exactly the same reasons that I became disenchanted with Occupy. It is a perennial problem. During the first two weeks of my Occupy it was really inspiring absolutely inclusive and so on. Then little hierarchies and cliques formed, people were asked to leave for certain misdemeanours and yes some of them probably were a little dangerous/dodgy in retrospect, the weather deteriorated badly, we decided to Occupy an old Jobcentre building, The inevitable eviction followed, the self-proclaimed ‘legal team’ were either too stoned or fast asleep to do the simple “this is a civil not a criminal matter, where’s your warrant, we are peaceful law abiding people peacefully resisting this eviction making sure they had a video camera going thing’. In spite of attempts to keep it going by having a weekly meeting the whole thing fell apart. Hierarchies, personal grudges, judgmental attitudes towards others all got in the way. I am happy to know many of the people I met there but everybody has gone ‘retour a la normale’ now.

For me though the most exciting thing was when Occupy London/Stock Exchange ended up at St. Paul’s … if only they had opened the doors and said ‘Yep come in. Our beliefs are actually very similar if not identical to yours … in fact let’s send out instructions across the Anglican Church for all Occupiers to be given accommodation in their local parish church’.

Now I think that would have ‘stopped some traffic’. I truly believe that the C of E is the proverbial ‘soft underbelly’ of the crocodile that is the British State. Now you can all have a good laugh at that!

Nice one, NP. I’m not going to have a go at the C of E; they’re all such nice chaps. I take your point though. I think unfortunately what you describe seems to be the fate of all such movements – cliques, fragmentation and infighting. That and very short attention spans and limited commitment levels.

BTW,. I’d love to see you write something about your own views, perspective and experience in regard to this subject.

Reblogged this on the burning blogger of bedlam.