“Every person has two homelands,” the French archaeologist Andre Parrot once commented; “His own and Syria”.

T.E Lawrence (of Arabia), who spent a great deal of time exploring Syria, wrote specifically of Palmyra; “Nothing in this scorching, desolate land could be so refreshing”.

It might also have been Lawrence who labelled Palmyra (or the ‘City of Palms’) as the ‘Venice of the Sands’; an appellation that continues to this day.

The Syrian Army’s recapturing of the historic city ends the so-called Islamic State‘s control of the area since May last year. The horror story of ISIL’s control of Palmyra – which has included the destruction of a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Palmyra alone has six) – will itself one day be regarded as part of Palmyra (and world) history; a particularly dark chapter in the long history of Palmyra that goes back at least 2,000 years.

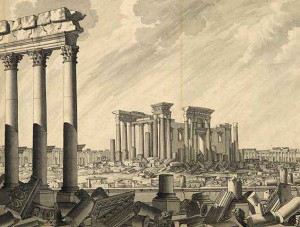

The famous British diplomat, spy, adventuress and Arab expert, Gertrude Bell recorded her visit to Palmyra in 1900; “I wonder if the wide world presents a more singular landscape”, describing the site and its “mass of columns ranged into long avenues, grouped into temples, lying broken on the sand or pointing one long solitary finger to Heaven”.

Gertrude Bell (portrayed by Nicole Kidman in Queen of the Desert and by Gillian Barge in 1992’s Lawrence After Arabia), a friend and contemporary of T.E Lawrence, is credited with having played a major role in the formation of modern Iraq (and founded Baghdad’s Archaeological Museum).

She put Palmyra on a par with the ruins of Petra (now in modern-day Jordan, but then part of the same territory).

Lawrence, who played his own part in helping shape the modern Middle East, shared Gertrude Bell’s feelings. His words are inscribed on a plaque in Palmyra; “Nothing in this scorching, desolate land,” he wrote, “could be so refreshing”.

The writer Agatha Christie appeared to have been mesmerised by Palmyra, judging by her recollection of it; “It is lovely and fantastic and unbelievable, with all the theatrical implausibility of a dream. It isn’t – it can’t be – real.”

Palmyra, like many ancient world sites, has its own myths surrounding it.

According to Hebrew scriptures, King Solomon was the founder of Palmyra; later Islamic legends attribute Palmyra’s founding to the supernatural ‘Jinn’ who are believed (according to the tradition) to have worked for Solomon. Both are more mythology than demonstrable historical fact, though Palmyra’s true, historic origin remains obscured in the mists of history.

Palmyra is claimed to have entered recorded history in around 2000 BC in the Bronze Age.

The name “Palmyra” is said to have appeared during the early first century AD, in the Roman works of Pliny the Elder. Pilgrims and merchants from all over the Near East came to or passed through Palmyra. Thriving as an oasis along the ancient caravan route between Damascus and the Euphrates, Palmyra’s engineers constructed complex aqueducts and reservoirs, and a vast temple complex easily equal to Athens.

The historic figure most associated with Palmyra was Queen Zenobia, who was born in 240 AD and claimed descent from Egypt’s legendary Queen Cleopatra. According to the classic historian Edward Gibbon, she spoke four languages, was famed for her chastity, and was “esteemed the most lovely as well as the most heroic of her sex”.

With the status of being a semi-independent monarchy, Palmyra was nevertheless a Roman colony. Zenobia was guided by the philosopher Cassius Longinus (not the Gaius Cassius Longinus who whispered in the ears of Marcus Brutus, nor the Cassius Longinus who supposedly participated in the crucifixion of Jesus) into declaring independence from Rome and engaging in war, Queen Zenobia even seized control of Egypt and reinvented herself as Queen of the East in true Cleopatra style.

The Emperor Aurelian saw no choice but to march on Palmyra, twice defeating Zenobia’s forces. The Queen, according to legend, tried to flee on camel but was captured, and Palmyra surrendered.

The Queen of Palmyra, like many other vanquished enemies of the empire before her, was paraded through Rome in chains.

Her ultimate fate is obscured to history. However, according to some accounts, Aurelian was so impressed with her character that he granted her freedom and even gave her a villa in Tivoli, where she supposedly married a senator and may have gone on to live out her days comfortably as a Roman.

But that wasn’t where Palmyra’s problems with Rome ended. In 273 AD, when citizens again rebelled against the empire and slaughtered a Roman garrison, Aurelian returned and this time laid waste to Palmyra. The temples were gutted and the city was left in ruin.

Palmyra didn’t recover from that event; and the ruin left by Aurelian’s forces remained the state Palmyra was essentially in for the many centuries to follow.

At the time Gibbon was writing, Palmyra was more or less abandoned and only some 40 families or so were reported to be living in mud huts within the court of an ancient temple.

Daniel Johnson wrote a particular good account of Palmyra’s history for Standpoint Mag last October. The rediscovery of Palmyra in the broad sense took a very long time, a key point being the publication in 1753 of what British antiquarian Robert Wood had experienced in his travels. Wood, who would later be the under-secretary of state to Pitt the Elder, published ‘The Ruins of Palmyra’, which did a great deal to revive the ancient city’s fame and stature across the Western world, along with the engravings and evocative drawings by Giovanni Batista Borra.

Palmyran influence was thus able to echo centuries beyond its time, particularly when such influential figures as T.E Lawrence and Gertrude Bell were writing about it in late nineteenth/early-twentieth century.

Some suggest that in the United States (newly independent at the time of Robert Wood’s work), Thomas Jefferson used the Palmyran Temple of the Sun as inspiration for the east portico of the Capitol Building in Washington (the eagle of the Great Seal may also be inspired by Palmyra).

_______________

The Islamic State’s occupation of Palmyra has sparked outrage around the world, amid fears that wanton destruction of historic and cultural landmarks would occur just as they had in Mosul and parts of Iraq.

Syrian military forces, who have in the last few days retaken the city from the jihadists, have in fact expressed great relief and surprise that the damage to Palmyra – though significant – hasn’t been nearly as bad as they had imagined.

The multi-national extremist group has looted or destroyed some of Palmyra’s most important sites and artifacts, including the Temple of Bel and the Arch of Triumph. But it has also left many of the sites intact. The Temple of Bel or Baal was regarded as the most important historic temple site in the Middle East after Baalbeck in Lebanon.

In early July, ISIL also destroyed the 1,900-year-old “Lion of Al-Lat” statue.

Curiously, in May 2015, Abu Laith al-Saoudy, representing ISIL’s military commander in Palmyra, had pledged not to damage the city’s historic buildings but to only destroy what were deemed as idolatrous statues. “Concerning the historic city, we will preserve it and it will not be harmed, God willing,” he had said. “What we will do is break the idols that the infidels used to worship. The historic buildings will not be touched and we will not bring bulldozers to destroy them like some people think”.

Despite the fact that they appear to have broken this pledge in some instances, it’s worth noting that the Temple of Bel or ‘Baal’ would’ve been seen very much as an object of past paganism or ‘idol worship’ and, in the minds of ISIL members, an affront to a puritanical view of the ‘one, true God’.

Such destruction has of course gone on throughout history, involving various religions and cultures.

On the other hand, ISIL also destroyed the Roman Arch of Triumph last October, which had no religious significance, and there have been a number of other acts of destruction, including ancient tombs.

However, before the ISIL takeover of the territory in 2015, prior Muslim Arab control of the city had never resulted in any damage or any hostility towards the monuments.

In fact, under the Ummayad caliphate, part of the Temple of Bel had even been used as a mosque; over the centuries, Muslim and Christian occupiers adapted some of the ancient sites to act as churches or mosques, but never sought to destroy or erase any of the ancient sites.

Tim Whitmarsh, a professor of Greek culture at the University of Cambridge, suggested that it was Palmyra’s nature as a symbol of multi-cultural and inter-faith synthesis that represented everything the ISIL mindset is opposed to. He wrote in The Guardian last August; ‘Palmyra is not just a spectacular archaeological site, beautifully preserved, excavated and curated. It also offers antiquity’s best counterexample to Isis’s fascistic mono-culturalism. The ancient city’s prosperity arose thanks to its citizens’ ability to trade with everyone, to integrate new populations, to take on board diverse cultural influences, to worship many gods without conflict‘.

When not motivated by simple religious puritanism, ISIL’s barbaric motives in damaging or destroying historic sites may also be simply to get massive publicity worldwide, cause outrage and seem incredibly powerful.

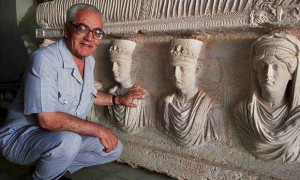

ISIL has also used the ancient sites in Palmyra as the setting for executions of Syrian Army soldiers and others. Most distressing of all, and more so than the destruction of the Temple of Baal or Arch of Triumph, was the brutal execution last year of 82 year-old scholar Khaled el-Asaad (see more). The Palmyra expert was interrogated for over a month by the militants, who wanted to know where a number of priceless antiquities were being hidden. Sick social media posts later showed the mutilated remains of Professor Asaad, with his severed head on the floor between his feet. His body was taken to one of Palmyra’s archaeological sites and hung from one of the ancient Roman columns for everyone to observe.

The restoration of Palmyra to government control is a massive victory, both strategically and psychologically; even foreign critics or opponents of the Assad government have been forced to admit this is an important moment – and one only made possible by Russia’s military intervention on the side of the Syrian state.

Director General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova, welcomed the operation and the expected liberation of the city of Palmyra, saying; ‘I welcome the liberation of the Palmyra archaeological site, martyr city inscribed on the UNESCO world heritage list, which carries the memory of the Syrian people, and the values of cultural diversity, tolerance and openness that have made this region a cradle of civilization’.

Talk in recent days has naturally turned towards how Palmyra’s damaged or destroyed sites might be restored for future generations, with even London’s Mayor Boris Johnson suggesting British experts should lend their skills to helping Syria with the rebuilding.

However, Mike Pitts, editor of British Archaeology, has taken a different, more cautious view of this. He says that Palmyra could be rebuilt to look at least superficially like the original. But he adds: “I think that would be wrong. Isis will one day be history. Palmyra will be its permanent lesson, about the darkness into which oppression, ignorance and corruption can sink. To over-restore the ruins would be to create a fiction, denying the tragedy and devaluing what had genuinely survived.”

It is certainly an interesting position to contemplate. Mr Pitts’ suggestion may in fact resonate somewhat with the idea of restoring Palmyra in a virtual sense rather than a physical one. On 21st October 2015, Creative Commons started an online repository of three-dimensional images published into the public domain to digitally reconstruct Palmyra (see more: http://www.newpalmyra.org/).

Meanwhile, the Syrian military said it would also use the reclamation of Palmyra as the staging ground for a further campaign to expel the ISIL militants from their ‘capital’ in the hijacked city of Raqqa.

It is worth considering, however, that as ISIL loses its territory (and in the case of Palmyra, possibly its access to lucrative artifacts), the organisation may turn instead to more attacks on Western and other targets. There are also fears that as the Syrian Army continues to push ISIL out of Syrian cities and towns, the defenseless territory of post-Gaddafi Libya may see more and more ISIL jihadists pouring in to Sirte, Tripoli and other cities now under extremist control.

In fact, Sirte is already being labelled the ‘new ISIS capital’; and indeed there have already been major concerns expressed that Libyan historic/cultural sites and artifacts (such as the stunning Leptis Magna) may fall victim to the jihadist philistines just as Palmyra did.

On December 11th, ISIL militants invading Libya announced that they had captured the ancient Roman city of Sabratha, a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the best preserved Roman archaeological sites in the Mediterranean. The dangers to Libya – a country left vulnerable and lawless by an illegal NATO/Western military intervention – may be about to increase.

But for Palmyra, at least this particularly grim chapter in its long history may now be over.

See more: ‘The Destruction of the Cultural/Historic Heritage of IRAQ & SYRIA…‘

See more: ‘The Tragic Story of Sirte: From Proud Libya to ISIL/Extremist Caliphate…‘

Palmyra

I don’t know what to say.

I can only look at pictures before the destruction……..

A haunting place.

I still cannot believe this throw back to the dark ages is happening.

Hi BBB, Maybe the post was too comprehensive. If you ping me your email address I will send it to you directly rather than post here. I’ve managed to recover a copy (phew!)

Hey man, I did email you a couple of days ago at what I think is your email address, so you should have my email already.

If not, just go to the contact page (at the top of the site) and contact me via that – I’ll receive your email address and message but your address won’t show publicly.

I’m sure you understand I don’t like to post my email address openly on the site.

I hope you got my post, I spent a couple of hours on it. Can you send me a copy back please. I’ve lost the original. Thanks

Hi Paul; I don’t know what post you mean. I haven’t received anything from you in the last few days.

Reblogged this on TheFlippinTruth.

Great Post

Reblogged this on HumanSinShadow.

Reblogged this on Lolathecur's Blog Below are two very important entries from the "Jewish Encyclopedia". Read them VERY CLOSELY..