The plight of blogger Raif Badawi in Saudi Arabia has garnered international attention, particularly in the context of the freedom of expression.

Badawi is facing a 10-year jail sentence (and I can hardly believe I’m having to say this in the 21st century, but 1,000 lashes in public) for the offense of expressing liberal, progressive ideas on his blog and therefore challenging the status quo within the oppressive kingdom.

He has been in prison already since 2012, with his Free Saudi Liberals blog put out of operation by the state.

His case puts this whole business of blogging into some perspective; the simple freedoms we (currently) have in our liberal societies aren’t a universal privilege, not even the liberty of being able to express one’s thoughts freely in a blog. The Guardian recently published some translated extracts from Badawi’s blog which though entirely non-aggressive in nature, does (somewhat gently) question the iron-fist rule of the Saudi state and certainly questions the role of religion in affairs of state.

What Badawi’s writings strongly explore is the diminishing of independent or progressive thinking in the modern Islamic world, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

“As soon as a thinker starts to reveal his ideas, you will find hundreds of fatwas that accused him of being an infidel just because he had the courage to discuss some sacred topics,” Badawi writes. “I’m really worried that Arab thinkers will migrate in search of fresh air and to escape the sword of the religious authorities.”

Badawi’s concern about the migration of “Arab thinkers” is particularly resonant, as Islam at the scholarly and literary level is perceived to be a culture in an age of stagnation, where more open dialogue and debate is repressed and where individuals who stray from the currently prevailing dogmas are not only ostracized but threatened and often killed.

This isn’t an uncommon event in, say, Pakistan, where blasphemy laws are in operation, but also where ordinary citizens will take it into their own hands to enact vengeance on anyone seen to be ‘blaspheming’ against the religion, the Koran or the Prophet.

In most cases that ‘blasphemy’ isn’t actual blasphemy anyway, but merely people questioning the currently prevailing dogmatic interpretations of Islamic law.

The near-fatal shooting of another blogger, the Pakistani teenager (and now Nobel Prize winner) Malala Yousafsai, was a disturbing demonstration of this violent brand of intolerance that exists in some of the Muslim world; in Malala’s case, she wasn’t ‘blaspheming’ against the religion, but simply speaking in favour of education for girls. Somewhere like Pakistan, the threat is from out-of-control elements of the community, often extremists taking law into their own hands in a country that has descended repeatedly towards lawlessness; while in Saudi Arabia there is no lawlessness or chaos of any kind – just the state and the will of the state.

In terms of the Saudi state, it doesn’t suit the totalitarian regime to allow any plurality of beliefs or opinions to exist in its society; once ideas, intellectual exchanges or reinterpretations of the religion are allowed any space, the prevailing dogmas of the puritanical state religion won’t be able to keep its grip on the minds of the population.

Meanwhile Raif Badawi isn’t just a symbol of the oppression within Saudi Arabia, but he is a symbol for the Islamic world itself; a brave voice trying to create or restore an open dialogue and examination to a society that has radically lost its ability to have conversations or to tolerate alternative interpretations. “States which are based on religion confine their people in the circle of faith and fear,” he writes.

On the matter of progressive, secular ideas and the Saudi state’s fear of such thinking as a threat to their absolute control, he says “They have succeeded in planting hostility to liberalism in the minds of the public and turning people against it, lest the carpet be pulled out from under their feet.”

Badawi received his first public flogging on January 9th; the next flogging has been postponed due to Badawi being judged unfit medically for the moment.

Amnesty International UK is petitioning the Saudi government to overturn Raif’s conviction and release him; you can add your voice to their petition by using this link and adding your name.

But what does all of this say about a state (Saudi Arabia) and the religion it is perceived to be the center of (Islam)?

Certainly, there is a widespread perception that Islam is an intolerant religion, where liberalism, freedom of thought or plurality of beliefs, doesn’t exist or isn’t allowed.

I earlier used the term ‘currently prevailing’ dogmas because there is a widespread misunderstanding among many people that this has always been the nature or condition of Islamic societies; but this hasn’t always been the case.

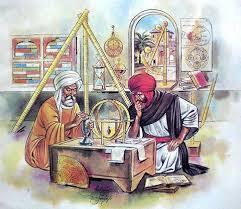

At different times in its history, the Islamic world has had other prevailing views or interpretations. If we go back to the earlier Islamic eras, in fact, the Muslim world was a culture of relative enlightenment, progressive thinking, science, medicine and philosophy at a time when Christian Europe was engaged in violent sectarianism, infighting, wars, Inquisitions, mass executions, persecution of minorities and of course incredibly bloody Crusades.

A key feature of the ‘Fatimid era’ for example, which originated in Syria in the 7th century, was the freedom afforded to the people and liberties given to mind and reason. People were free to believe whatever they liked provided they did not infringe upon others’ rights.

The Fatimids reserved separate pulpits for different Islamic sects and scholars expressed their ideas in whatever manner they wished. In that era patronage was given to scholars of varied origins who were invited from various places and financially supported, even when their ideas contradicted the prevailing belief system.

This was at a time, remember, when the 16th century Renaissance in Europe was still many centuries away yet.

As Sasha Brookner notes in an article for The Huffington Post, “Between the ninth and 13th centuries, the libraries in Baghdad, Damascus, Timbuktu, Cordoba and Cairo contained more books, manuscripts and literature than in the entire Greek world.”

The torch of what we think of as ‘civilisation’ and intellect was in fact being carried by the Islamic world for a long time – and not by medieval Europe or the West.

Sadly the view upheld by the Abbasids that “the ink of a scholar is more holy than the blood of a martyr” is one that has no place in the Saudi state’s contemporary religious dogmatism that has successfully penetrated deep into much of the Muslim world. This vague-in-length ‘golden era’ of Islamic culture is regarded to have been brought to an end by the Crusades launched from Christian Europe, which put the medieval Muslim world under greater pressure to defend itself, and later also by the aggression of Gengis Khan and the Mongols from further East.

But even beyond those eras, the Islamic world broadly maintained some degree of progressive thinking, liberty of interpretation and discourse, with a wide variety of different forms and schools of Islamic thought able to flourish in places like Egypt, Syria and Iraq, for example.

The diminishing of all of this and the rise to dominance of the most intolerant, puritanical form of Islamic thought has been a relatively recent phenomenon.

And its chief architect has been Saudi Arabia and the Wahhabist-centered ideology that has spread out across different parts of the Muslim world, manifesting as ‘Salafism’, ‘Takfiri’ movements and most insidiously infecting scores of mainstream Sunni Islamic thought and ideology.

This was accomplished through immense Saudi wealth and its funding of Wahhabi-derived literature and ‘educational’ material that has been disseminated out across the world for decades now: in large part tolerated or even enabled by Britain, the US and the Saudis Western allies.

Long gone are the days when Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba were renowned world capitals of culture, learning and intellect.

A key point in time where some manner of renaissance or restoration of those past cultural peaks might’ve occurred was after the First World War and the freeing of the Arab world from the Ottoman Empire; but instead the Middle East was carved up into Colonial ‘spheres of influence’, sectarian divisions formed and Saudi Arabia was established by Western powers as the heartland of the Islamic world, which would eventually lead to the diminishing of the plurality and liberty of interpretation that had once existed.

This harsh, regressive school of Islamic thought is the ideological root of present-day radicalization on a mass scale (albeit, along with other factors such as economic conditions or foreign military impositions or encroachments).

It is worth noting too that the real founders of the ‘Arab Revolt’ in World War I – and the real proponents of Arab independence and modernisation – were not the Saudis but the Hashemite Arabs (principally under Faisal bin Hussein during and after World War I). And the Hashemites, as noted in this article, had wanted a modernised Arab world with relatively liberal ideas, freedom of religion, and a pluralistic culture more in keeping with those perceived Golden Ages.

But the Colonialist British and French powers abandoned their war-time allies in favor of the Sauds and the Sykes-Picot carve-up of the region: and thus, essentially, in favor of the extreme, puritanical brand of Islam attached to the Saudis and to the religious sectarian strife inherent in the Colonialist geo-political settlements.

That was then.

And that was the major turning point that saw diminishing prospects for the liberalisation of the Islamic world and saw the empowerment instead of a less tolerant and more oppressive school of Islam to be nurtured.

Fast-forward to now.

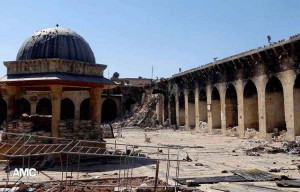

And, extraordinarily, both the US-led ‘War on Terror’ and the more recent ‘Arab Spring’ actually seem to have led to an expansion of this intolerant/puritanical version of Islam into places where it previously was being suppressed: such as in post-Baathist Iraq, post-Gaddafi Libya, post-Mubarrak Egypt and in war-torn Syria.

Curiously, though Saudi Arabia is considered the nation most complicit in the 9/11 terror attack that instituted the ‘War on Terror’, it has never been included on America’s list of rogue states or state supporters of terrorism: instead, the US targeted countries like Iraq and Syria – where religious and cultural pluralism existed and where the extreme strand of Islam didn’t have space to flourish… until now.

In war-torn Syria, post-war Iraq and in post-Gaddafi Libya, the Wahhabi-inspired extremists have been able to invade and spread their version of twisted Islamic fundamentalism (witness the spread not only of Al-Qaeda, but the birth of the so-called ‘Islamic State‘). The cancer has even spread through parts of Africa, such as in Nigeria, giving rise to groups like Boko Haram.

How much of this is by design? That is a question I grapple with in this separate article. But the shape and direction of geo-politics and foreign policy raises questions about whether the perceived decline of intellect and the increasing medievalisation of Islamic thinking has been a sought-after conspiracy.

Saudi and Gulf State actors were known to be actively involved in the jihadist extremism in Syria from 2011 onwards; and likewise in the jihadism that characterised the overthrow of Gaddafi and the Libyan State in 2011. This was to the extent that “Al-Qaeda Imams” were being installed into mosques in Libyan towns and Wahhabi preachers were appearing in Syrian towns to inspire jihadist Syrian rebels.

Add that to the $1 Billion in funding that Saudi Arabia and Qatar provided to, for example, Libyan and foreign Islamist militias to overthrow Gaddafi and you have to conclude that Saudi Arabia has been directly supporting jihadist extremism in foreign countries – in concert with US/UK-led foreign policy programmes and regime-change operations.

The decline, therefore, of intellect and free thought in the Islamic world can not only be traced – over several decades – to the Saudi-aligned Islamist ideologies, but can in fact be seen happening right now in a more blunt, violent fashion.

At the same time as the Arab Spring revolutions were going on in Egypt and Tunisia, praised and championed by Western democracies, people in Bahrain tried to do the same, standing up to their oppressive royal rulers and campaigning, via non-violent means, for more rights and liberties; the Bahraini citizens were harshly cracked down on by the Bahraini state and with full Saudi approval. There was no expression of solidarity or support for the citizens of Bahrain from the Western governments during their hour of need; yet when very small initial protests were hijacked by terrorist infiltrators and agent-provocateurs in Libya and Syria both Western governments and the corporate media went into overdrive, expressing their support for ‘the people’ and calling for both Gaddafi and Assad to stand down.

While much of this hinges on Western geo-political operations, the role of the Saudi state is undeniable.

This isn’t necessarily an attack on King Abdullah or any specific Saudi King or royal at any given time; there are some who will praise King Abdullah for some of his reforms and (relatively minor) gestures towards some limited modernization of Saudi society.

The problem is bigger and deeper-rooted than any individual figurehead or policy-maker, but resides with the religious clerics and powers that have been nursed within the bosom of the Saudi state for decades.

History demonstrates that the Islamic world, in previous centuries, was not only carrying the torch for civilisation and intellectual advancement – it was also the bastion of liberalism during times when the Western world was certainly not.

And it could’ve returned to that condition, could’ve experienced its own Renaissance – particularly after World War I. But decisions were made and policies pursued – by various vested interests and powers in various places – to ensure that this didn’t happen.

It, in fact, seems as though similarly vested interests and powers in various places are operating today – in the 21st century – to keep it that way.

Reblogged this on Saine Corner.