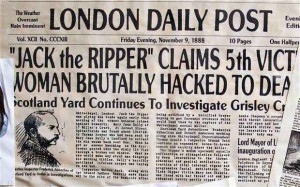

The last couple of days have seen a resurgence in the popular interest surrounding the 125-year mystery of Jack the Ripper.

This being in the wake of amateur investigator Russell Edwards declaring he has decisively exposed the identity of the infamous serial killer.

Websites and newspapers in the passed two days have featured headlines to that effect, painting this latest hypothesis as a conclusive, definitive statement on the matter.

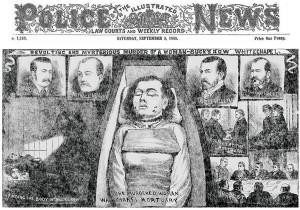

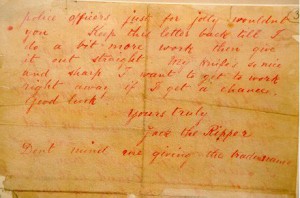

The mystery of Jack the Ripper has fascinated generations. Why has the Ripper legend endured for so long and inspired so much imaginative reinterpretation and analysis? Partly it’s because of the nature of the murders, which were both surgically precise and brutal; but more than that it’s because of the mystery of the killer’s identity, further amplified by those famous, taunting letters that may or may not have been written by the Ripper himself.

Though not the first recorded serial killer, Jack the Ripper was the first criminal case to create a global ‘media frenzy’ and was therefore a watershed in the convergence of crime and sensationalist journalism that we now see as the norm.

The bleak image of the brutal gentleman murderer stalking the gas-lit streets of Whitechapel by night is as much an archetypal vision of Victorian London as the opening passages of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol; and the mystery of who slashed the throats of those five women and then surgically disemboweled them has never been decisively solved, with over a hundred different suspects implicated over the years, many of them based on highly fanciful or spurious reasoning.

This often fanciful list of suspects has included, among others, Alice in Wonderland author Lewis Carroll, children’s charity campaigner Dr Barnardo, the grandson of Queen Victoria, and even a Sioux Indian warrior named Black Elk, who had been in London in the 1880s as part of a touring Wild West show.

This latest hypothesis, courtesy of Edwards, centers on DNA evidence found on a shawl at one of the murder scenes and the DNA testing of descendants of both victim and suspect to see if they match the shawl DNA.

According to this claimed breakthrough, the Ripper is identified as Polish-born Aaron Kosminski, one of the longstanding suspects in the case. Edwards May or may not have found the decisive clue to the Ripper mystery; but someone essentially emerges every several years or so with a new theory on the Ripper’s identity and usually with a book to sell too – which Mr Edwards has, titled Naming the Jack the Ripper.

I’m not pooh-poohing Edwards’s hypothesis at all; the processes involved in his investigation are themselves fascinating, it’s an interesting story and his conclusion is plausible, of course (the citing of Kosminski, however, as the killer isn’t a revelation; again Kosminski was a key suspect from the very beginning).

My reflexive hesitation with this buzz around the Edwards case is that it feels like manufactured coverage.

This is exacerbated by the language; “We have definitively solved the mystery of who Jack the Ripper was,” Mr Edwards is quoted by The Independent as saying. “Only non-believers that want to perpetuate the myth will doubt. This is it now – we have unmasked him.”

If nothing else he’s getting an extraordinary amount of publicity for his book. Some, however, and particularly those in the scientific community, have already begun to express guardedness towards these proclamations by both the author and those covering his story; it is pointed out, for example, that the molecular biologist credited with providing the case its scientific evidence – a Jari Louhelainen of Liverpool John Moores University – hasn’t so far published his methodology in any peer-reviewed scientific journal where it can be analysed or verified.

I’m not, however, trying to rain on Mr Edwards’s parade; I love the tradition of ‘amateur sleuthing’ – or “armchair detectives” as Edwards calls himself. And when it comes to the Ripper case, this tradition has more or less become an institution.

But there has very recently, in fact, been another ‘conclusive’ hypothesis forwarded on the Jack the Ripper case too. The enduring mystery of the identity of Jack the Ripper may have been resolved by former Murder Squad Detective Trevor Marriott who has spent 11 years conducting a detailed cold-case analysis of the infamous murders.

Having trawled Scotland Yard’s files and applied 21st century police techniques and modern forensic analysis, Marriot believes the myth of ‘Jack the Ripper’ was largely the creation of a London-based news reporter named Thomas Bulling.

In 1888 Thomas Bulling was working London-based Central News Agency, though also had several contacts at Scotland Yard, the theory being that Bulling was hired to concoct gripping and sensational crime stories for the newspapers. Marriot believes Bulling forged at least one letter to Scotland Yard in 1888 pretending to be the infamous Jack.

Mr Marriott has discovered at least 17 unsolved murders with Jack the Ripper type properties occurring between 1863 and 1894 and believes a German merchant seaman named Carl Feigenbaum was responsible for some of those killings, though not all of them.

Feigenbaum was an infamous presence aboard ships regularly docking near Whitechapel; he was eventually executed in New York in 1896 after being caught trying to flee the scene of a Ripper-esque murder there.

The picture being painted by Marriot is that there was no single, definitive ‘Jack the Ripper’ figure, but rather a scattering of similarly brutal crimes over several years; and that it was journalistic artfulness that furnished the situation with its more dramatic narrative and the various evocative elements that would ensure the long-term propagation of the myth. “The reality is there was just a series of unsolved murders and they would have sunk into oblivion many years ago but for a reporter called Thomas Bulling,” Mr Marriott has said in regard to his research.

So could the infamous Ripper, as Marriot suggests, in fact have been an (at least partly) engineered myth?

It’s possible.

He makes a strong case. On the other hand, the Ripper murders – we are told – were so peculiar, so surgically precise, and so singularly brutal that it is hard to accept that there was more than one person carrying them out: as the acts seemed to be so highly individualised and so suggestive of a personal agenda or message.

Then again, if – as Marriot suggests – the newspapers were manufacturing the more mysterious side of the narrative to enhance the story, then it might make more sense.

Which, if either, of these two latest theories should we take the more seriously? As already stated, there are already so many theories, both in the more sober, academic-styled vein and in the more creative vein of the arts. Literature of the late Victorian era, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s early Sherlock Holmes stories and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, has laid long-term foundations for subsequent writers and interpreters and has often resulted in aspects of these fictional adaptations being merged with the real-world information about the Ripper murders, thus adding to the confused overall picture many people have of the case.

The key addition to this mix was Stephen Knight’s 1976 work Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, which expanded on theories involving the royal family, Freemasons, and the medical profession that have come to be associated with the Jack the Ripper mythology.

Knight’s implicating of the royal family and Freemasonry has been influential ever since. For example, Murder by Decree, starring the great Christopher Plummer as Sherlock Holmes (with the late, great James Mason as Watson), follows the masonic and royal conspiracy idea popularized by Stephen Knight and has a royal physician being the murderer.

Even 1972’s The Ruling Class, a satire on the British aristocracy starring Peter O’Toole, links the Ripper murders to the British upper class. O’Toole’s character, the mentally ill 14th Earl of Gurney, spends part of the film believing he is himself Jack the Ripper and performing a pair of Ripper murders.

The interesting thing about both these latest theories – from Marriot and Russell, respectively – is that neither of them play to the royal, masonic or aristocratic element that has been so prevalent for several decades.

Which they don’t have to, of course: if the two respective researchers earnestly investigated and came to their own honest conclusions (that didn’t involve the upper-class element), that’s entirely legitimate.

I guess my problem is that I’ve become so used to the royal/masonic angle (or maybe even indoctrinated by it) that I instinctively struggle a little to look beyond it. Which could be testament to the power of accumulated mythology rather than any reflection on what the plain truth is or isn’t.

But let’s revisit the alleged masonic/royal conspiracy here for a moment, in the interests of balance and scope.

Knight’s central claim was that the Ripper victims were murdered to cover up a royal scandal: an alleged secret marriage between Queen Victoria‘s son Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, then second in line to the throne, and a Catholic prostitute named Annie Elizabeth Crook, who supposedly bore Albert’s child.

Much of Knight’s information purported to come from Joseph Gorman-Sickert, who claimed to be the illegitimate son of painter Walter Sickert (who was himself a Ripper suspect).

According to this narrative, a high-ranking Freemason and physician named Sir William Gull actually committed the murders: in order to eliminate everyone who knew of Prince Albert’s secret marriage with a prostitute. Gull was a reputable physician who had treated members of the royal family.

In fairness, Knight’s theory would explain why all the victims were alleged prostitutes. Gull being a surgeon would explain why the murders were allegedly so surgical in nature, claimed to have been conducted by someone with strong knowledge of anatomy. And if the killer was a Mason and someone linked to the royals, it would explain why he was allowed to escape capture or identification: and why, instead, a long-lasting ‘mystery’ and mythology was allowed to flourish concerning Jack the Ripper.

Knight also points to a symbolic and ritualistic nature to the murders, which he argued was based in Masonic ritual symbolism.

On the other hand, the Masonic/Royal conspiracy has – it is widely claimed – been debunked and discredited. Though adherents to this theory would argue this apparent debunking is merely a continuation of a cover-up for the sake of the royal family and the Freemasons. As is known, Knight’s main source – Joseph Gorman-Sickert – later stepped back from his story and claimed it had been a hoax.

Which, one would have to assume, is true. And, for one thing, it has always seemed possible Sickert invented the story in order to fully clear the name of his alleged father. Knight even claimed himself that he initially considered Sickert a fantasist.

But might he also have been pressured by an outside influence to retract his story? Now I know that sounds like we’re stretching here – trying too hard to make the royal/masonic theory work.

But there’s something else we should bear in mind here.

In 1970, a Freemason named Sir Thomas Stowell gave an interview in a newspaper called The Criminologist and a BBC interview: in which he had claimed that he had access to all the Ripper files, with the implication being that the Duke of Clarence was in fact Jack the Ripper.

Like Sickert, Stole recanted his story a week later. But then, one week after this, he was dead.

Firstly, Stowell was a man of aristocratic stock, a physician, a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons and had received the CBE. And he was 85 years old at this point in time. Why would he make up a claim about knowing the identity of Jack the Ripper – only to recant it a week later?

Why would he go so far as to give interviews, including to the BBC, to make this claim – and change his mind seven days later?

And, again, he was also a Freemason. Why would a Freemason and someone with aristocratic links implicate a member of the royal family in the Ripper murders?

It just doesn’t sound like something someone in his position would do. The fact that he died a week later makes it all the more suspect.

The same week, Stowell’s son reported that he had burned his father’s papers, saying “I read just sufficient to make certain that there was nothing of importance.” Really? If there was no evidence to support Stowell’s claim, then why burn the papers?

It would actually make sense that someone in Stowell’s position – a Mason, someone with royal and aristocratic connections, and a physician – might somehow have had access to incriminating Ripper files that might’ve been passed down to him. Stowell had said his information came from the private notes of the same Sir William Gull that Knight theorises committed the murders. Stowell knew Gull’s son-in-law, Theodore Dyke Acland, and was an executor of Acland’s estate: so the line of transmission would seem to make sense.

One can’t help but feel that Sir Thomas Stowell – for whatever reason – did have access to incriminating files, and – for whatever reason – decided to go public with it. And was then pressured or intimidated by someone or someones into quickly ‘recanting’ his implications.

For that matter, Stowell’s apparent recanting didn’t actually appear in print until the day AFTER he died (with the now deceased man supposedly writing “I have at no time associated His Royal Highness, the late Duke of Clarence, with the Whitechapel murderer”).

It’s all very odd. The accepted account of Stowell’s behaviour doesn’t make sense. And it’s this story, more than anything, that keeps me at least partly camped in the royal/masonic conspiracy hypothesis.

Did Sir Thomas Stole even die of natural causes?

We’ll never know. And we’ll never who Jack the Ripper really was or why he murdered those women.

The various theories mentioned above are just the tip of the iceberg of Ripper lore in various mediums; it’s difficult to think of many other real-world events that could match the Ripper murders for sheer volume of subsequent mythology, theory and counter-theory.

A definitive truth isn’t even possible anymore. The truth in fact might be some labyrinthine combination of multiple ‘theories‘. For example, what if Knight’s theory of a royal conspiracy is true, but that the whole ‘Jack the Ripper’ mythology – including the alleged newspapers’ sensationalism, as posited by Marriot – was designed to muddy the waters and divert attention away from any royal or masonic involvement?

One can’t but feel that the party that would benefit the most from the sheer volume of alternative and contradictory Ripper ‘theories’ would be the perpetrators or maintainers of a high-ranking (as in royal or masonic) conspiracy.

If there was a cover-up from the start, then it would benefit that cover-up to have multiple red-herrings and distractions proliferate. It all quickly became smoke and mirrors – and it has remained that way ever since.

Even Marriot’s suggestions about Thomas Bulling essentially inventing the ‘Jack the Ripper’ persona could be argued to play into this: with newspapers playing up the mythical character (particularly with the Ripper letters) in order to assist the cover up. Certainly, the police might’ve aided a cover up (as has been suggested by many): and if there was a Masonic element, then we know that the police have always been linked to the Masons, so that make sense.

And, as Marriot’s book suggests, Thomas Bulling had close ties to the police. What’s to say the newspaper didn’t have masonic, royal or high-level links too – and therefore a motive for ‘creating’ (as Marriot suggests) the ‘Jack the Ripper’ persona and storm?

But again, the matter will never be laid to rest. There will always be a new theory.

Most people interested in the matter don’t actually care for the truth but for the dark romanticism of the myth and its associated imagery, folklore and pseudohistory. When something becomes that embedded into popular consciousness for so long, the idea in itself becomes self-sustaining and independent of the shackles of historical truth.

And again, that in itself benefits whoever the original conspirator or conspirators were or was.

The only inescapable fact is that those women died horrible, horrible deaths. And, actually, a book well worth reading is The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold, which attempts to shift the balance and tell the stories of the five murdered women and reconstruct their lives.

Whether ‘Jack the Ripper’ existed in the classic archetypal form we’re familiar with or whether he was a phantom summoned up by journalistic inventiveness, ‘he’ nevertheless lives… to forever stalk the misty Victorian Whitechapel streets in the dark corners of our collective consciousness and nightmares.